How Post & Beam, the successful black-owned South L.A. restaurant, stayed in local hands

The soul of a restaurant can be hard to trace, a heady synthesis of atmosphere and mood, the food on the plates, and the people who make that food and arrive to eat it.

The soul of Post & Beam, the 8-year-old restaurant in the back of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw plaza in South Los Angeles, was palpable on a recent Sunday morning as folks gathered for a brunch of oxtail hash or fried chicken and waffles on the outdoor patio, and a jazz duo (standing bass, alto sax) held court before Cara Cara orange trees and an herb garden.

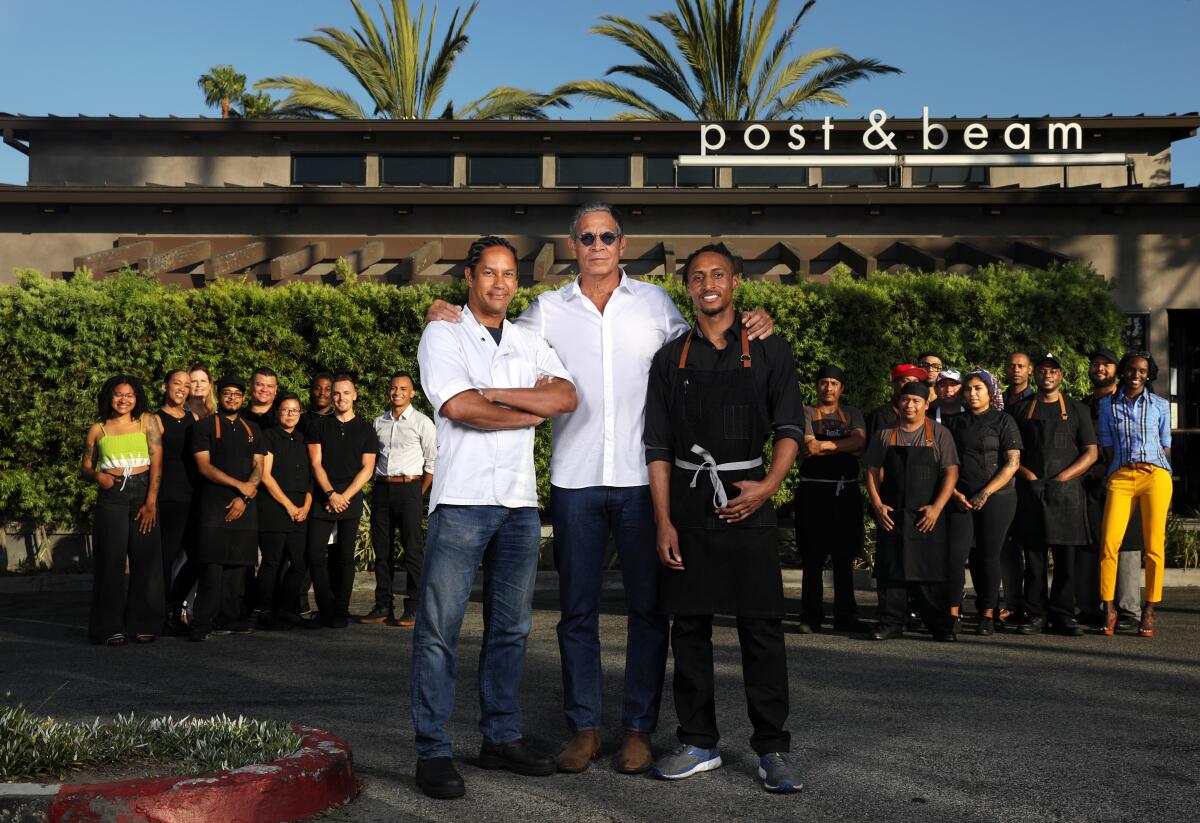

And it was very much on display one night in late July, shortly after restaurateur Brad Johnson, 62, the restaurant’s founding owner and operator, handed the keys (proverbial, actual) to chef John Cleveland, 36. With Govind Armstrong, 50 — Johnson’s opening chef-partner at Post & Beam, Cleveland’s mentor, the restaurant’s current consultant and one of the founding chefs of California cuisine — the three men had spent years building a restaurant by and for their community, a black-owned, -operated and -envisioned business in a neighborhood that needed and deserved it.

“I intended to bring in an African American chef when I first got approached with the project,” Johnson told me over a plate of Cleveland’s excellent catfish. “But when I looked at Jonathan’s list,” he said of the late Jonathan Gold’s list of best Los Angeles restaurants, “I noticed this concentration of dots in West Hollywood, the Westside, downtown. Then they do a flyover of South L.A. and land in Redondo Beach. It’s as if South L.A. didn’t even exist. And I said: That can’t happen with this restaurant.”

When Johnson opened Post & Beam, on New Year’s Eve of 2011, he did so with Armstrong behind the stoves. The chef, who began his celebrated cooking career as a teenage apprentice at Spago, had the kind of cachet Johnson was looking for — plus he was local, and he was black.

“You know, I’m not retiring,” Johnson said, a playful smile recalibrating the few lines on his face. “I am probably retiring from the restaurant business, though never say never.” This caveat is probably hardwired, as Johnson’s resume is a long one, spanning 30 years as a restaurateur, first in New York and then in Los Angeles. That resume includes running the Roxbury (the setting of “Night at the Roxbury”); years with Georgia (notable partners Denzel Washington, Norm Nixon — whom Johnson met while playing basketball at UMass — and Debbie Allen), site, Johnson notes with heavy irony, of the O.J. Simpson defense team post-verdict party); BLT Steak with chef Laurent Tourondel; and Willie Jane, the Venice restaurant Johnson ran with Armstrong that closed in 2016.

What Johnson is doing is shifting gears, both his own and that of the restaurant, and handing it over with as much deliberation as he had at its inception. He readily admits he thought about putting the place on the market. “But I didn’t want to do that,” he said. “My fear was that there would be somebody of means who would come in, someone not from the community. What a loss that would be.”

The dining room was standing-room-only on a weeknight, servers navigating plates of jerked catfish and cast-iron chicken, the tables filled with a mashup of regulars, locals and friends, many of whom detoured to give Johnson a loud greeting, a hug or a handshake. It felt a little like a politician’s campaign party even before Greg Dulan, owner of Dulan’s Soul Food Kitchen, came over to say hello, telling Johnson about his day with Joe Biden, who had been stumping in East L.A. and had taken over Dulan’s restaurant with an apron, a television crew and a pack of Secret Service agents.

The two men, both second-generation restaurateurs — Dulan’s father, Adolf, opened Aunt Kizzy’s Back Porch in L.A. in the ’80s; Johnson’s father, Howard, ran the celebrated Manhattan restaurant the Cellar for over 20 years — commiserated. Kim Prince, Dulan’s business partner and a third-generation restaurateur, chatted with Johnson’s wife and longtime business partner, Linda. And Cleveland and his wife, Roni, now the restaurant’s maître d’ and events director, threaded their way through the crowd, the ownership transition seamlessly effected with deft smiles and deferential conversation. Because for the soul of a restaurant to migrate to its food, it has to start with those who engineer it.

Cleveland began cooking at Post & Beam two years ago, though both he and his wife had been regular diners long before that. Originally from Oakland, his family moved to North Carolina when he was in high school. “My grandmother’s a chef. My dad is a pitmaster; he didn’t go to culinary school,” Cleveland said. “I started as a grill cook, I’ve worked as a busboy, I’ve washed dishes, I’ve hosted, served the tables. I bartended when I was in college.” After UNC Chapel Hill, Cleveland moved to Los Angeles, where he did private and contract cooking and met his wife.

“We have a son, so he’s from South L.A. now too,” said Cleveland of his 2-year-old. “I wanted to commit to being a chef in South L.A. Being able to hit it off with Brad and Govind at the right time was a blessing; it was a dream come true.

“I wish we could see more of this,” Cleveland said of how Johnson and Armstrong brought him in and of Johnson’s decision to sell him the restaurant outright. “There’s so much space up for lease. For me, I didn’t see any other place to go where I’d have this kind of support and this foundation.”

Spicy, intensely flavored jerk seasoning takes especially well to catfish fillets, like those at Post & Beam restaurant in Baldwin Hills. Here’s the recipe.

“John was such a lucky find,” Johnson said, then contextualized what might seem like a glib statement with some of the backstory of what it meant to open Post & Beam in South L.A. “It’s not a bad neighborhood. You go up the hill this way and it’s Baldwin Hills, Ladera Heights, View Park,” he said, numbering some of the wealthier black neighborhoods in the city, even the country. “But Santa Rosalia, our cross street, is almost the equivalent of the tracks.”

Johnson said that before the restaurant opened, they ran a hiring ad on Craigslist. “This was 2012, 2011, and this part of town was still coming out of the recession. I come from the days in New York when you ran an ad and 400 people showed up for a cocktail waitress job. I thought we’d be overwhelmed. We had 50 or 60 people show up — only four African Americans. In this community. It was shocking.”

He paused, remembering.

“I also think that there’s a psychological scar — and it probably relates as much to front of the house as back of the house — and it’s the servitude issue. A lot of black folks will not choose these jobs even if these are the only jobs.” The staff at Post & Beam, Johnson says, is now predominantly African American.

“It took a while for the kitchen that we currently have to find us. Govind’s name was known, but there’s a small black culinary pool; it’s just tiny. So John found us because he wanted to work in a Govind Armstrong restaurant,” said Johnson.

Later I asked Armstrong if he’s felt like a role model for African American chefs over the course of his long career, which has included a roll call of California restaurants: Campanile, City Restaurant, Postrio, Chadwick and Table 8.

“One hundred percent,” Armstrong said. “There’s not enough of us out there. It’s gotten a little better over the last five or 10 years; it could be ‘Top Chef,’ ‘Iron Chef,’ the Food Network and people coming back to their roots. More people are cooking the food of their heritage.”

As for his continuing involvement with Post & Beam, the chef — who recently moved with his family to West Adams, just a few minutes away from the restaurant — was adamant:

“It’s beyond just a project for me. I would not give it up for anything.”

Post & Beam: 3767 Santa Rosalia Drive, Los Angeles, (323) 299-5599, postandbeamla.com.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.