Jonathan Gold’s fried chicken

Though he was most famous for his writing and his eating, Jonathan Gold was more than just the belly of Los Angeles. He often arrived at restaurants on what felt like Gold Coast Time: unconnected to reality or agreed-to plans. While some of that was just how he was, if you prodded, he’d often have an excuse: He had cooked dinner first for Leon, his son, and had usually eaten with him.

Leon’s lunches and dinners were the final destination for the leftovers of the restaurant meals you over-ordered with him, sometimes remixed by Jonathan: The building blocks of his pantry included the food you’d be waiting in line for a few weeks later.

“In the early years, he didn’t cook,” food writer Ruth Reichl, a longtime friend, told me, “so he’d sort of forage meals from restaurants.”

Jonathan Gold remembered in (mostly) his own words.

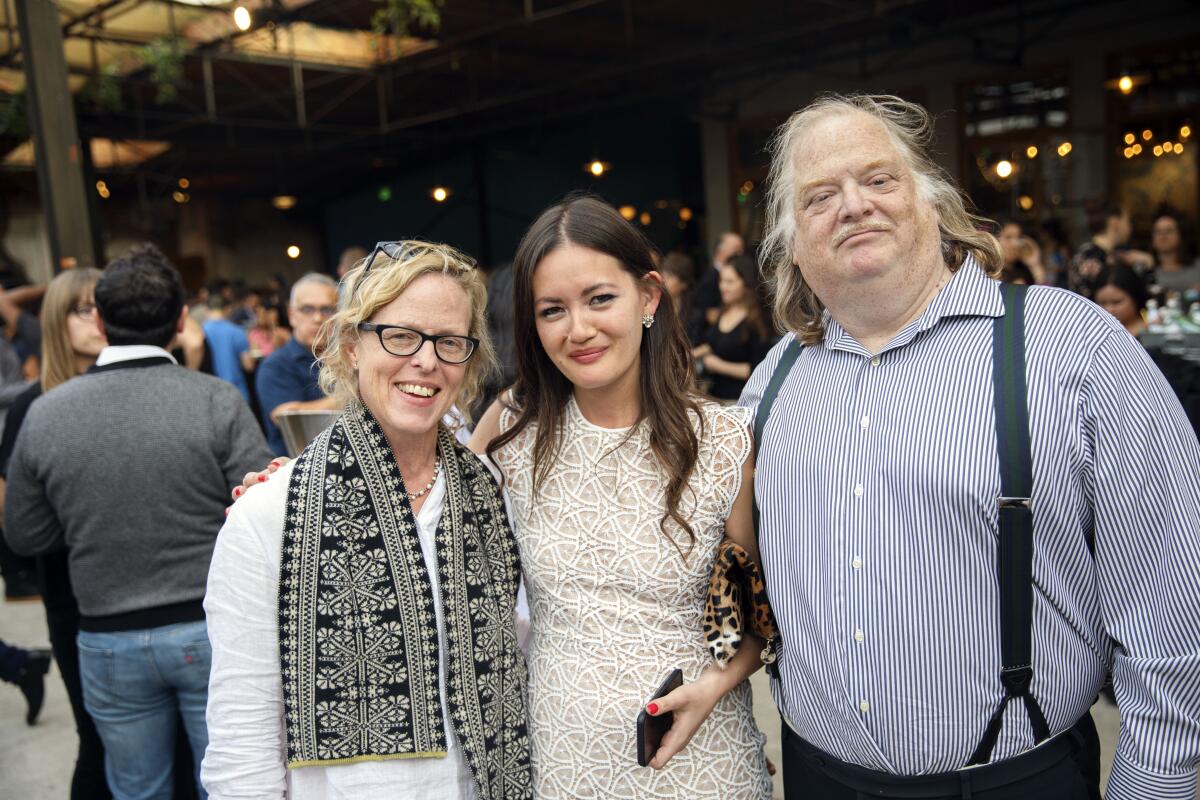

She and I never ate Jonathan’s cooking — a surprising shared discovery we had while I was putting this edition together — though many of his friends did. (I blame Chester, the Gold family’s too-furry tabby, whose dander kept me at bay.)

Jonathan and I often texted about cooking. He was inquisitive and insightful — full of delightful little one-upsmanships, like during our last text exchange, when I was developing a recipe for cedar-grilled salmon, and he recalled Mark Peel serving it at Campanile when I was still in short pants, passing a branch of burning thyme over it before it was served. (I have, of course, incorporated that move into my routine, if for no reason other than the beauty of the ritual.)

We remember Jonathan Gold with the gift he gave to everybody whether they ate with him or not.

When you poll his friends, what you find is that when he was gathering people at his house in Pasadena for a night off from eating out, that fried chicken was what he made.

The funny thing about it is that, like an urban legend, there are certain details everyone remembers and others that vary from eater to eater. For a guy who spilled it all on the page, who let his life be captured on film for a documentary, it was probably good to have a couple secrets in the tank, particularly when it came to the too-rare times he let loose at the stove for a crowd. (Though, as Bill Addison pointed out to me, this recipe bears the heavy thumbprint of Edna Lewis, who brined, buttermilked and county hammed her chickens, and was a name Jonathan would drop in reviews from time to time, undoubtedly steeped in her writings.)

Here are some collected tellings of Jonathan’s chicken routine, from friends, family and colleagues:

Amy Scattergood, L.A. Times food writer: “When I remember Jonathan Gold, I often picture him across an overloaded restaurant table, or lingering beside a taco truck or staring off into space in front of his laptop in his office at the newspaper. But most often I think of him in his kitchen, standing barefoot at his stove, frying chicken.

“Jonathan loved restaurants more than anyone I ever will know, but he loved cooking for his family and friends even more. He could probably cook most anything, but whenever I went over for dinner he was mostly making his take on comfort food: pots of red beans and rice, gumbo, hoppin’ John, roasted meats and birds, skillets of vegetables. And fried chicken.

“He’d stand at his stove, tongs in hand like a conductor’s baton, his own children weaving around him along with the collection of old friends for whom dinners at the Gold house were built into the year like a church calendar. If asked, he’d discourse on his cooking methods while veering into tangential anecdotes about the Lakers or Husserl. For years, he made a version of David Chang’s fried chicken, or so he told me. I once looked for the recipe, and it didn’t seem much like what landed on Jonathan’s picnic table; maybe he invented this, maybe I did. But I think the recipe changed with his mood and his ingredients, which were often sourced as idiosyncratically and last-minute as his stories.”

Laurie Ochoa, Jonathan’s wife and L.A. Times arts and entertainment editor: “As far as I know, he may have read countless fried chicken recipes, including the one in the first Momofuku book, but then tinkered with things himself. He had two basic fried chicken plays: one where he would use country ham and lard from the local carniceria, and one where he would use olive oil, which sounds prissy but actually is perfect after a piece of the lard chicken.

“He’d get big brown paper bags and shake the chicken in flour, salt (and sometimes Dario salt), often oregano and lots of pepper. He’d also marinate the chicken overnight in buttermilk. Pretty basic stuff done right.

“Leon has been able to approximate this in small batches, with his own addition of a hot rub based on Hattie B’s recipe, plus a good dose of Magma powder from Michael Cimarusti’s brother-in-law.”

Evan Kleiman, friend and host of KCRW’s “Good Food”: “Jonathan’s was the best fried chicken I ever ate. It was objectively delicious, but what pushed it over the top for me was that it was the physical embodiment of what I had in my head from childhood: Fiction was as close as I came to fundamentals of Southern cookery as a young Angelena. Chicken, shallow fried in a cast iron skillet with its dark spots from where pieces touched the pan, only existed in Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ ‘Cross Creek’ novels or on ‘The Andy Griffith Show.’ Jonathan made the fiction real. And it was even better cold.”

Margy Rochlin, writer and family friend, took notes on Jonathan’s fried chicken, which informed the recipe below: “By cooking just pounds and pounds of chicken, he really perfected it. He’d fry the chicken in deep Le Creuset Dutch ovens, the big ones. He’d use two different types of flour, different brown paper bags of seasoning.

“It was supposed to spend 24 hours in brine and 12 hours in buttermilk spiked with hot sauce. But he’d often skip the brining — my guess is that there wasn’t 24 hours’ worth of enough real estate to park all the chicken in their refrigerator.

“I can picture it so clearly: For most of the party, he’d be standing in bare feet, right next to the never-used microwave that, over the years, had become a place for storing napkins, dressed in a pink Brooks Brothers shirt and beige khakis, frying chicken for hours. He always made something like meatless beans, earmarked for Manohla Dargis and other vegetarians. Leon and I would often be on collard green duty, removing the leaves from the thick stems. Michelle Huneven would show up with a big bag of mixed greens, just picked from her garden, and make a big salad. Jervey [Tervalon] would always show up late, but we’d get the roux going for his gumbo.”

Jenn Harris, L.A. Times food writer: “When you received a text from Jonathan asking you to go eat something, the reply was always yes. When the text involved an invite to his house to eat fried chicken for his annual Fourth of July party, the reply was hell yes.

“I remember Jonathan’s as the best in the universe. I showed up at his party and found him frying multiple pans of chicken all at once, the stove completely covered, the smell intoxicating and the sound of grease popping all around us. He told me he was frying some of the chicken in olive oil and some in lard. Would I please try it immediately and tell him which I preferred?

“The chicken fried in olive oil was spectacular. It was like a cross between the stuff you’ll find at Willie Mae’s in New Orleans and Thomas Keller’s Ad Hoc bird. But I often think about that chicken fried in lard. The coating was crisp, then melted in your mouth with a foie gras unctuousness.

“Seated in his backyard with an olive oil-fried drumstick in one hand and a lard-fried thigh in the other, surrounded by his family and friends, I remember thinking that I was the luckiest girl in the world.”

There is no guarantee that the recipe below will earn you the adulation that Jonathan’s earned him, though it’s a good place to start.

Jonathan Gold’s Barefoot Fried Chicken

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.