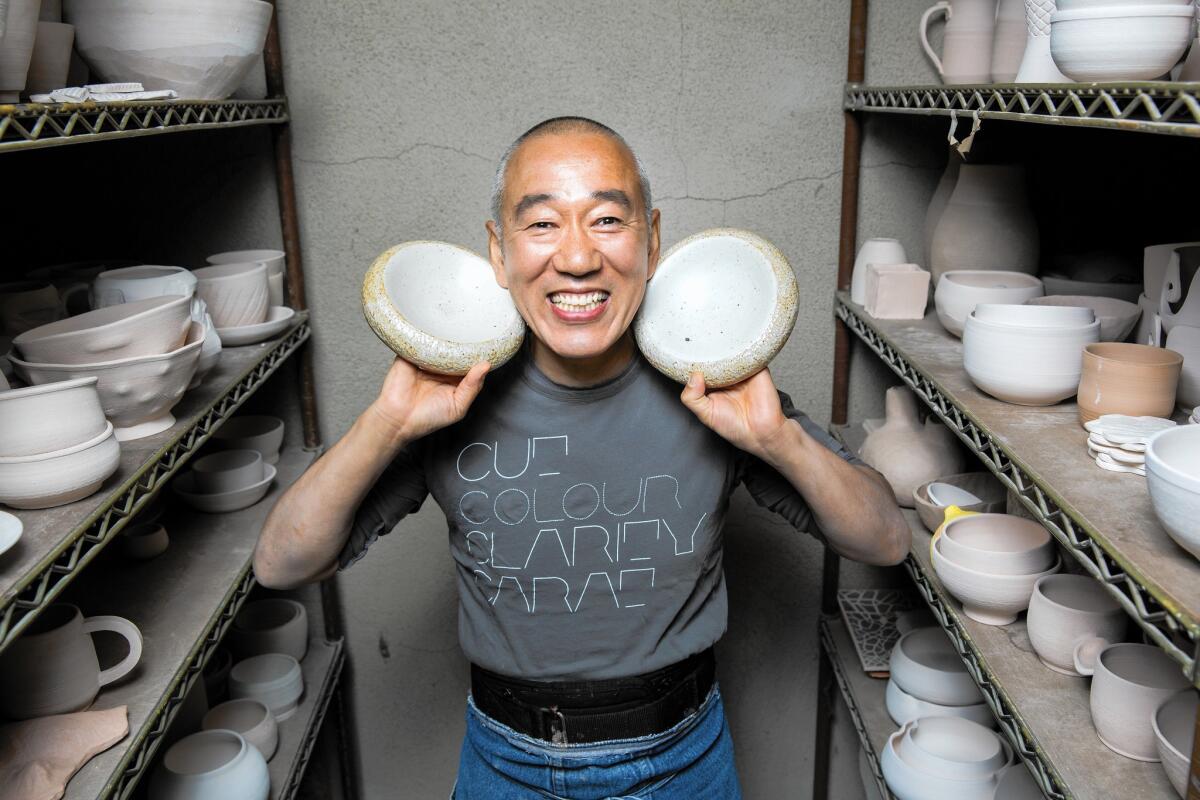

Morihiro Onodera turns his culinary artistry into pottery creations

“I used to dream of sushi. Every day,” says Morihiro Onodera “Now I wake up in the middle of the night with an idea for a plate.”

The former owner of Mori Sushi is obsessed with making pottery. Behind his Los Angeles sushi restaurant, he had two potting wheels and a kiln, and whenever he had a few minutes, he would be at the wheel, forming a lump of clay into a bowl or plate.

Four years ago, Onodera sold his sushi restaurant to a longtime employee and now spends much of his time making ceramics for a roster of illustrious restaurants, including Providence in L.A. and Mélisse in Santa Monica. But that’s just one of his three jobs. Another is growing Japanese rice in Uruguay. The third is making food once in a while.

Chefs love control, and sushi chef Mori Onodera exercises about the maximum amount of control a chef can have over food served at a restaurant.

Onodera, who is from Fujisawa in the Iwate prefecture of Japan, came to the U.S. at age 21 (he is now 51). In the 1980s, he worked as a sushi chef at Katsu on Hillhurst Avenue, R-23 downtown (both gone now), and in the ‘90s at Matsuhisa on North La Cienega Boulevard and Takao in Brentwood. He opened Mori Sushi in 2000.

Over the years, Onodera became friends with the chefs who came to eat his exquisite nigiri-zushi and omakase. He remembers when Michael Cimarusti, Josiah Citrin and David Kinch made their first trips to Japan and fell in love with the ceramics at restaurants in Tokyo and Kyoto. “They wanted those plates. But the prices were so high, sometimes $6,000 for a single piece, so they asked me if I could make something similar — cheaper, more reasonable for them,” he explains.

The chef could and did. One plate led to another, and now Onodera creates startling and unique serving pieces for Providence, Mélisse, Il Grano, Orsa & Winston and Capo. He’s created special plates for Manresa in Los Gatos, Calif. Napa Valley’s three-star Michelin restaurant Meadowood has some of his bowls too. None of them is white.

“My goal is not just to make pottery. My goal is for chefs to present food on my pottery.” And each piece he makes is a collaboration between potter and chef. His biggest inspiration is the late legendary Japanese calligrapher and ceramicist Rosanjin Kitaoji, who also had a Tokyo restaurant.

From afar, Stephanie Shih’s most recent ceramic work looks like something pulled from a grocery shelf: a bottle of Chinkiang vinegar, a gallon can of Kikkoman soy sauce, a 50-pound bag of rice.

Onodera keeps photos of his favorite pieces on his iPhone, showing off images of the lipstick red bowls he made for Providence and plates with a shallow circular depression for sauce commissioned by Josef Centeno for Orsa & Winston. For Mélisse, he made bowls with wide rims pierced with tiny holes. Up pops a photo of a huge red-glazed platter with an indentation for dipping sauce. “I made that for Dario Cecchini,” Tuscany’s renowned Dante-quoting butcher, says Onodera. Onodera says that Capo’s Bruce Marder hand-carried the piece to Cecchini at his shop in Panzano-in-Chianti, complaining all the way.

The potter now works at Xiem Clay Studio in Pasadena, where he has 24-hour access. When an idea comes to him in the middle of the night, he can go there right then and begin working

No newfound enthusiasm, his interest in pottery goes as far back as his days as a sushi chef at Katsu and R-23, where he was inspired by the work of ceramicist Mineo Mizuno. He never had the time for pottery then. During a brief stint working in New York, though, he squeezed in a single Saturday morning class in hand-built ceramics at Greenwich House Pottery. After that, he taught himself. “I don’t like a class. Not even cooking class,” says Onodera.

When he’s not making ceramics, Onodera works on his second, even bigger project: growing rice and teaching people how to cook it. “What is sushi? It’s not all about the fish,” he says. “60% is about the rice, 30% the fish and 10% skill — maybe more.”

At Mori Sushi he used his own California Delta-grown rice, polishing just what he needed each day. He grew that rice with his friend, rice farmer and researcher Ichiro Tamaki. In 2005, Tamaki and Onodera began growing a Japanese cultivar in Uruguay. “It’s 32 hours from my door to the rice field,” says Onodera, shaking his head as if he can’t quite believe he signed on for this.

We’ve made it to Peak Ceramics: All your friends are taking wheel-throwing classes, Brutalist planters have become status symbols, and every other upscale restaurant has commissioned its own run of handmade plates and sconces.

Their Japanese short-grain koshihikari variety is sold to some of the same restaurants Onodera makes plates for (Mélisse, Providence and Orsa & Winston) under the label Satsuki and is also available retail at McCall’s Meat & Fish Co. in Los Feliz.

But what about cooking? Does he miss his restaurant? Would he open another one? “I’m taking a long break,” says Onodera, who seems quite content with his current occupation — or rather, all three of them.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.