Appreciation: Anthony Bourdain opened the working-class kitchen to the world and the world to us

If you spent much time in food circles around the year 2000, you knew that American food culture was beginning to change — and not necessarily toward the embrace of the seasonable, sustainable, organic pleasures promised by the food revolution. Chefs had been part of popular culture for years. What was new was the idea of the kitchen — the sweating, bleeding, cursing crew of cooks and dishwashers, the maelstrom of sharp edges and leaping flames, the battle-hardened camaraderie of men and women working together in submarine-tight proximity.

Anthony Bourdain’s first articles for the New Yorker, which became the foundation for his first book, “Kitchen Confidential,” slashed through the walls separating working-class cooks from their soft, well-fed customers, and for perhaps the first time since George Orwell’s “Down and Out in Paris and London,” elevated the rough humanity of the kitchen above the soft pleasures of the table. It is hard to imagine the current American restaurant scene, powered by the beauties of hard work, loud music and love, without him. It is hard to imagine an aspiring chef without a worn copy of “Kitchen Confidential” sitting by the bed.

Bourdain wrote for the people with sheet pan burns on their arms and bits of flour stuck in their hair; for the people who found the deepest parts of themselves inside the stinking cavities of the pigs they were breaking down for dinner service; and for the people who cursed equally well in English and in Spanish. His best pieces tended to be not about great chefs, but about people like the cook who cut every piece of fish served at a three-star gastronomic temple but who had never eaten in the restaurant.

Full coverage of Anthony Bourdain’s death »

His greatest fame likely came with his food/travel television series, hopping from the Food Network to the Travel Channel and then finally to CNN. From the beginning, Bourdain was most interested in the intersection of food and culture, and a shot of a fish on a plate would usually be preceded by an exploration of the people who had cooked it, sold it in the market or landed it on their boat. He didn’t ignore the world’s great restaurants — some of the best episodes involved places such as El Bulli or Restaurant Paul Bocuse, and Le Bernardin’s Eric Ripert, who reportedly discovered Bourdain’s body in a hotel room this morning, was a constant presence both onscreen and off — but even there the emphasis was more on the people who loved food than on a sauced hare’s disembodied presence.

“Parts Unknown,” his series for CNN, at times fused the culinary with the political. Bourdain looked for answers about the future of places such as Libya, Ethiopia and the Punjab region of India through their food cultures, and he was occasionally less than optimistic.

From the outside, his last year seemed devoted to combating sexual harassment through his passionate advocacy of the #MeToo movement. (His girlfriend, Italian actress Asia Argento, has accused Harvey Weinstein of rape.) He was also publicly mournful about his role in toxic male kitchen culture, which he may have helped to cultivate with his earliest writing, but which he forcefully denounced in later years.

From In-N-Out to Chateau Marmont, Anthony Bourdain understood what makes L.A. great »

“I’ve had to ask myself…” he told Slate last year. “To what extent in that book did I provide validation to meatheads?”

The outpouring of grief in the food world the morning after his death is overwhelming. I counted 38 consecutive Bourdain posts in my Twitter feed this morning before I gave up and closed the app.

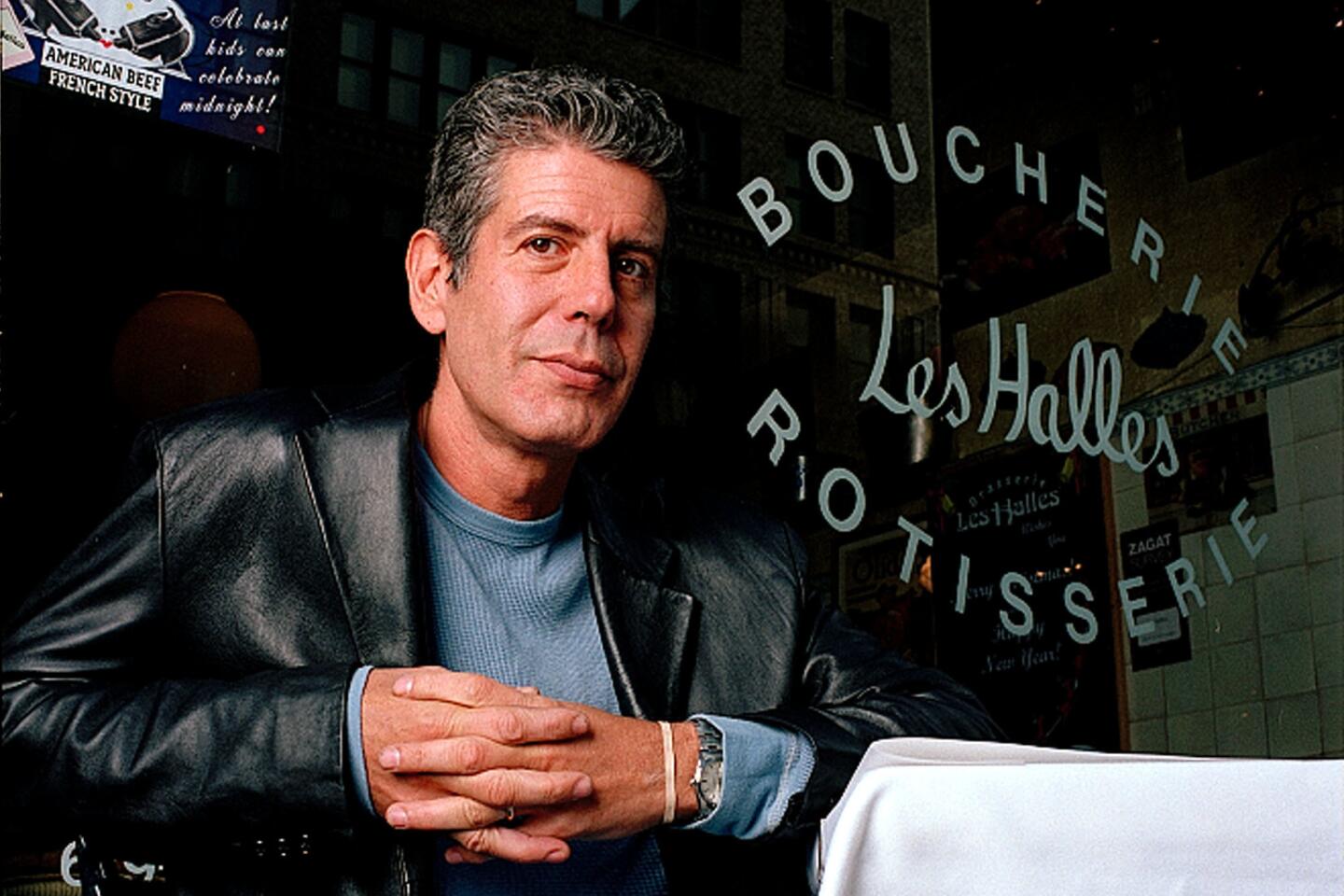

I met Bourdain for the first time in 2001, just before “Kitchen Confidential” was released, when he tagged along with a mutual friend to lunch in the Meatpacking District. I had recently called his restaurant Les Halles my favorite New York bistro in the old Gourmet magazine, but he was completely uninterested in that — he interrogated me about an L.A. Times review I’d written of Oki Dog a few years earlier, and why I was sending him to an iffy Los Angeles neighborhood to eat pastrami burritos and whether the hot dog wrapped into a tortilla with fried cabbage said more about L.A.’s changing demographics or about my dubious taste. He couldn’t have been less interested in the usual chef gossip.

I didn’t know him well — there is an informal firewall separating restaurant critics from chefs, and probably from TV people as well — but he would periodically email me to ask about an Indonesian dish he was looking for or chat about an author he was thinking of signing for his imprint at Ecco Press. He said kind things about me in his later books. I was delighted to see his influence grow to transform and then transcend cooking — the “Parts Unknown” episode hour he spent with President Obama in the Hanoi bun cha restaurant was charming.

And I cannot imagine how the food world is going to cope with this gaping Bourdain-shaped hole — not at its center but on its fringes, looking exactly like a man throwing rocks at the status quo.

If you or a loved one is considering suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255.

ALSO

Anthony Bourdain was the eternal compadre of overlooked Latinos

Anthony Bourdain’s death stuns girlfriend Asia Argento and celebrity admirers

Cooking for comfort? Anthony Bourdain’s rich lasagna Bolognese is one of our favorites

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.