Nancy Silverton looks back at 25 years of La Brea Bakery

It has been 25 years since Nancy Silverton started La Brea Bakery. In some ways, she says, it seems like yesterday. In others … “I sometimes think a bakery measures years like dogs,” Silverton says. “What is it with dogs? Seven years for every human year? With bakeries, it sometimes seems like it’s more like 10.”

Indeed, the story of La Brea Bakery, one of the truly iconic food businesses in Southern California history, has all the makings of a television mini-series. Improbable successes, bitter fights, financial crashes -- there’s a little bit of everything in the La Brea saga.

So it will probably be with a mixture of pleasure and relief that Silverton cuts the ribbon Thursday on the bakery’s newest expansion -- a large café on La Brea Avenue, just up the street from the original bakery location. The party will run from noon until 3 p.m. with free samples and plenty of swag.

It’s hard to imagine just how bad the bread scene in Los Angeles was before the La Brea Bakery opened. There was already a bread revolution going on in the Bay Area, where Steve Sullivan’s Acme Bakery had been baking breads with natural sourdoughs since 1983. But in the Southland, the fluffy, overly sour stuff from Pioneer Boulangerie was the best that was available.

La Brea Bakery changed all that. Suddenly, Southern California had a bread that was the equal of any anywhere. Indeed, in 1997, a par-baked loaf of La Brea Bakery bread won the San Francisco Chronicle’s tasting of sourdoughs -- a victory so disconcerting that the Chronicle ran a retest to be sure, and the La Brea loaf scored even higher the second time around.

But in fact, Silverton wasn’t even planning on opening a bakery when she and her then-husband Mark Peel were scouting spaces for the restaurant they were hoping to open. She was definitely interested in baking -- at the time she was running the pastries at Wolfgang Puck’s Spago while Peel ran the line. Puck had wanted to start a bread program, so she’d looked into it.

“What I found was that unless you were really set up for it, it wasn’t very profitable to make your own bread,” she says. “You need to have a dedicated space and you need to do wholesale to make money at it.”

And restaurants with enough space to run a separate bakery were scarce. But when she and Peel found the Campanile spot -- at the time a chopped-up mess of various businesses on a somewhat dingy stretch of La Brea Avenue -- she realized that there might be enough room for her “side project”.

Actually, thanks to the vagaries of restaurant construction and permitting, La Brea Bakery opened before Campanile -- in January of 1989 while the restaurant opened in June. It was not an auspicious start.

“When we initially opened, we didn’t even have anybody working the counter,” Silverton says. “We had a bell on the door and when you opened the door it would ring and I was mixing dough in the back and would come out and take the order.”

There were a few rough spots at the beginning.

“The first thing, we were a bakery, and so people were very surprised to see no cakes there and that made some people mad,” Silverton says. “There was another lady who kept coming in and telling us the bread was dirty, because it had flour on it. There were complaints about too many holes -- the peanut butter kept falling through.”

But it quickly became clear that Los Angeles had been waiting for a place like La Brea Bakery.

“It took a little while to win people over, but when we were selling out at 11 a.m. or 1 p.m. every day, we realized we were on to something.”

Silverton says the first time she really realized the magnitude of how big a hit they had on their hands was the Thanksgiving of 1990, when the line to buy bread stretched around the block and partway down Sixth Street.

But all that business created other problems. Scarcity does build demand to a certain extent, but when they were constantly selling out by lunchtime, it was clear the business needed to expand.

“We were just bursting at the seams,” Silverton says. “It was impossible.”

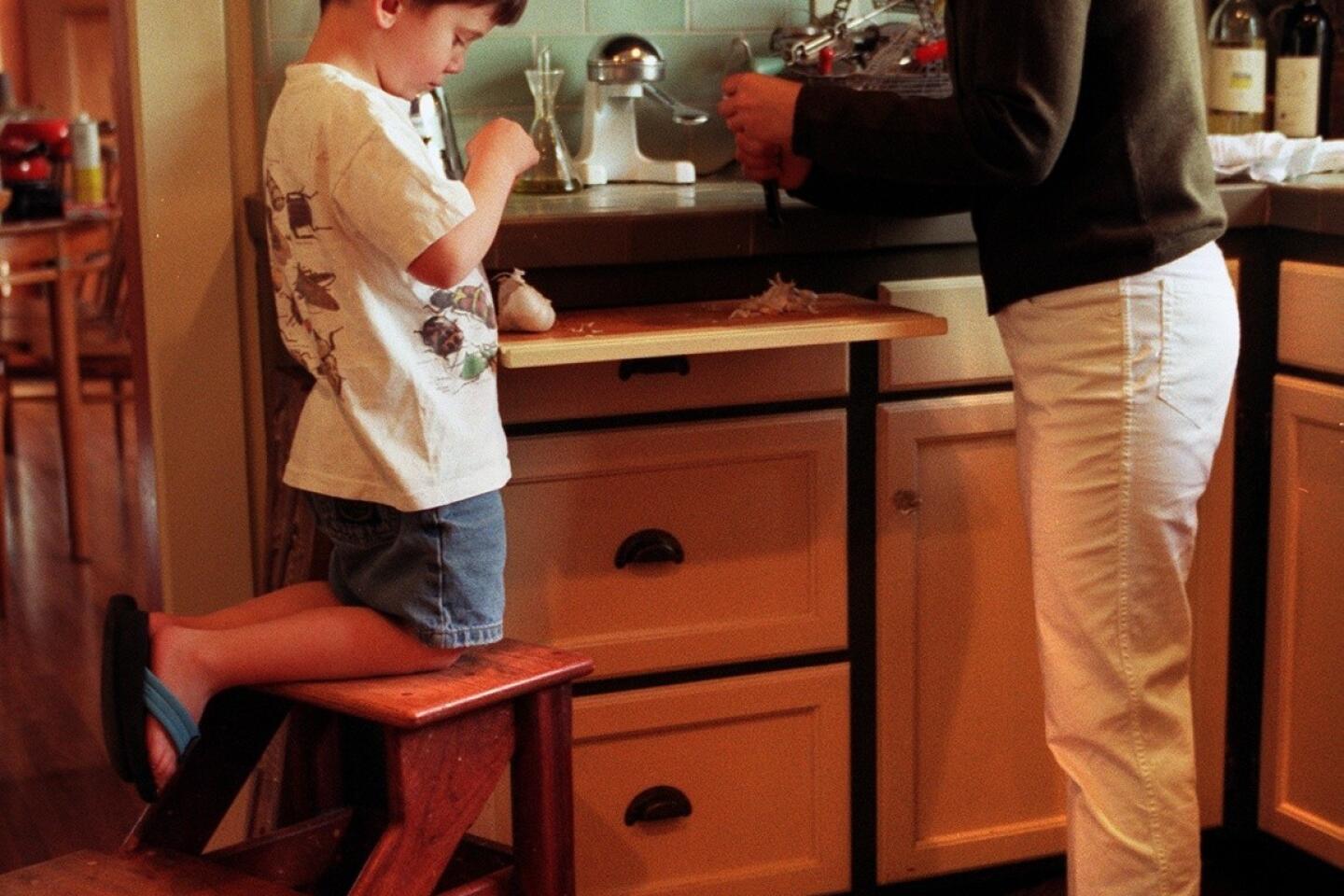

Besides, Silverton was working herself to a frazzle, not only supervising the baking at La Brea, something that involved a baker’s highly erratic sleep schedule, but running the desserts for Campanile, and helping raise her and Peel’s two kids.

So two years after opening, Silverton and bakery General Manager Manfred Krankl, now a noted Central Coast winemaker, went back to the same group of investors who had funded Campanile and got the money to build a much larger, fully staffed, commercial bakery on Washington Boulevard.

At the time, they also split the bakery off as a business separate from Campanile. “It became clear that the bakery was going to be a home run,” Silverton says. “It was then that Manfred had the foresight to legally separate the two. We knew that if we wanted to grow it, which we did, whoever was going to buy it would not be interested in buying a restaurant at the same time.”

In 1998, they expanded again, opening a huge commercial bakery in Van Nuys that would allow them to produce par-baked loaves that could be shipped around the country.

“Soon after we had moved into the Washington facility, we were approached by a frozen food company and they asked if I would be willing to partner up with them in the sourdough frozen dough business,” Silverton says. “My initial thought was ‘absolutely not’. Me freeze something? But I never say no to something without trying it and at least looking at the end result.”

That experiment didn’t work. (“There were too many variables and we couldn’t get a product we could control.”) But the seed had been planted. Krankl suggested par-baking -- baking the breads to 80% done and then freezing and shipping. They experimented in the Washington Boulevard facility, found they could bake very good bread that way, and raised the money to open the Van Nuys plant.

Shortly thereafter, in 2001, the Irish came calling. The investment group IAWS, which already had a par-baking group in Europe, was looking to expand into the Unites States and snapped up La Brea Bakery for a price that has been variously quoted as anywhere from $56 million to $68.5 million.

That was a huge success by any measure. But then, Silverton’s share of that take -- more than $5 million -- disappeared in 2008 with the collapse of Bernard Madoff’s pyramid scheme. She had invested the entire amount with him.

Still, she bounced back almost immediately with the opening of the highly successful Mozza complex of restaurants, which she owns with partners Mario Batali and Joe Bastianich.

Silverton hasn’t been closely associated with the bakery since before the birth of her third child, Oliver, in 1993. “I turned over the ovens,” she says. “What I did do, I was still there for quality control and as an advisor. Which is sort of what I still do.”

At the new café, she has been working with chef Hourie Sahakian to fine-tune some of the dishes that will be served. But the company also has a long experience with running a restaurant -- it’s got a long-running spot in the Disneyland Resort as well as kiosks in airports, hospitals and entertainment venues around the country.

Looking back on 25 years, Silverton marvels at how her little bakery grew, but also wonders that there hasn’t been more competition.

“Look, I know, when you’re the first kid on the block, you’re going to steal the show, no question,” she says. But she wonders why a bread scene hasn’t flourished in Los Angeles that would equal San Francisco and New York.

“After we opened La Brea Bakery, I was surprised at how long it took for more bakeries to open. In San Francisco, when Acme opened, there were other bakeries right away. And in New York, too.”

Silverton points out it’s not like there are many grand mysteries about bread baking remaining. “There are too many bakers for inspiration,” she says. “There are too many classes available. There are too many bread books. When I started out, when Steve [Sullivan] started out a few years before me, there were none of those resources. There was Elizabeth David, Bernard Clayton, ‘Beard on Bread’, ‘Laurel’s Kitchen’ and Julia Child’s baguette recipe.

“Really, today there’s no excuse for baking bad bread.”

La Brea Bakery Café, 624 S. La Brea Ave., Los Angeles, (323) 939-6813.

ALSO:

Neapolitan pizza comes to East Hollywood

Suzanne Goin talks about “AOC Cookbook”

“Bitter Singles” Valentines at Josie Next Door

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.