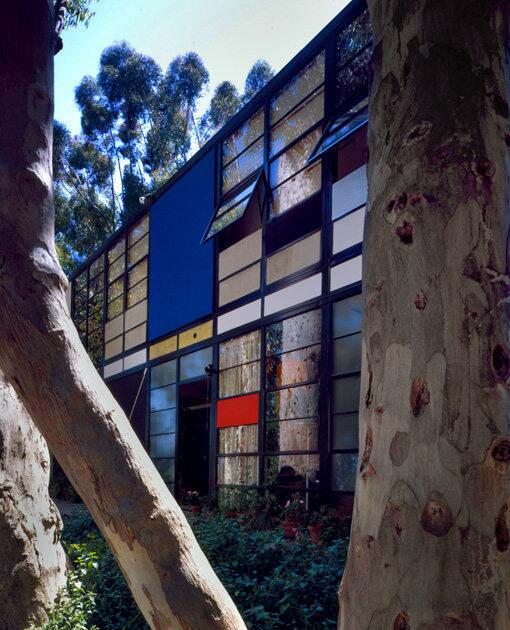

Landmark Houses: The Eames House

The Eames House in Pacific Palisades stands as an epitome of Midcentury California design, an expression of modernity and optimism that many still emulate today. Said Bill Stern, founder of the California Museum of Design: “The Eames House eschewed traditional materials like bricks and sticks, and used glass and steel in fresh ways to create a new understanding of how people can live.” (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

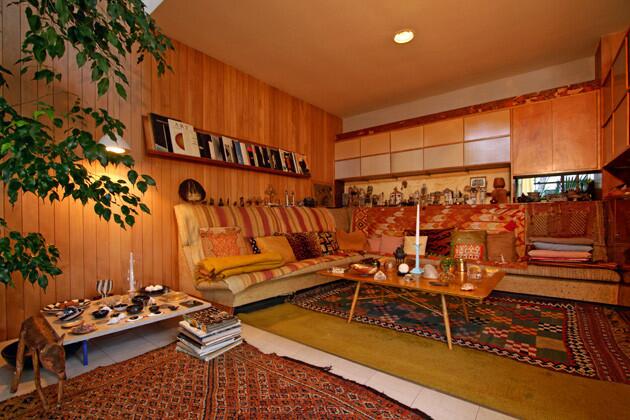

Charles and Ray Eames nurtured a design imagination that knew few boundaries, but if you were to look for its center — its heart — you might have found it in their living room. With its 17-foot-high ceiling, panels of glass opening to a grove of eucalyptus, and a vast range of objects collected over a lifetime, the Eames House living room is where two of the most influential designers of the 20th century spent hours talking, entertaining friends and playing with the collections that informed their work. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The living room does not resemble the type of rigorously formal space that people today expect in a modern house from the era. Even though the Eames House is a wonderfully calibrated exercise in steel, glass and concrete panel, inside, the architecture takes a back seat to the extraordinarily diverse collection of objects. Here, an American folk art crow decoy. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

A Chinese lantern hangs in front of one of the same house plants that, quite amazingly, can be seen in historic photos of the house. Since the Eameses’ deaths – Charles in 1978, Ray exactly 10 years later, to the day – a caretaker has kept the house in a state of suspended animation, as though Ray has simply the left the house on an errand. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A stool designed by Lucia Dewey Eames, Charles’ granddaughter, and given to Ray as gift. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

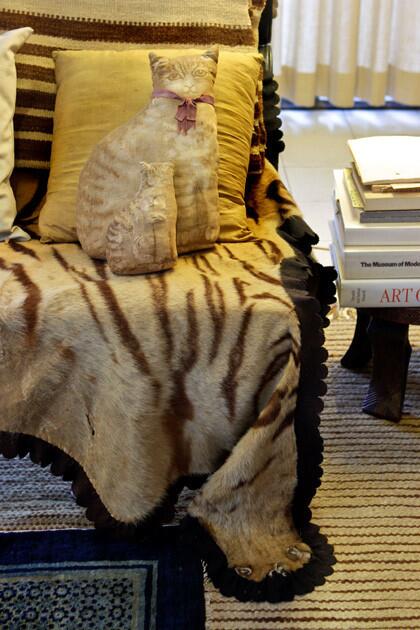

Consumed by a quest to put their ideas about play and freedom into material form, Ray and Charles Eames were continually excited by how others, especially in cultures far from their own, expressed themselves. They filled their living room with hides, shells, stones and folk art from around the world. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The bookcase was built at the Eames Office. The ladder reaching toward the corrugated steel ceiling allowed Charles to rearrange hanging light fixtures and string paintings face down, parallel to the floor, so if one were to look up, one would see a gallery on the ceiling. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

A Tlingit ceremonial oar from the Pacific Northwest hangs from the ceiling. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

More collections on the living room bookcase. Placement of every object was critical. “Ray would always be moving things around,” said Pat Kirkham, the author of “Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century.” “Mostly it was few inches here or there, but how everything aligned intrigued her.” (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

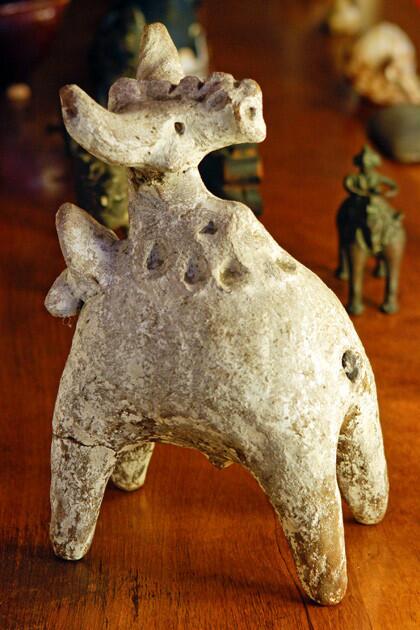

A white-painted terra cotta folk sculpture of Nandi, the bull of the Hindu god Shiva, sits on the living room bookcase. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

An alcove off the living room. Though it has been suggested that Charles was responsible for the hard, architectural edges and Ray did the soft interiors, Charles’ grandson Eames Demetrios said the partnership wasn’t that simple. “Charles was trained as an architect, Ray as a painter, but they had a holistic collaboration, where each was the other’s most important sounding board,” he said. “Their collaboration was always blurring the line between technology and art, and their designs flowed from an understanding of the materials and the needs of the user.” (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

In the living room alcove, a feather fan with wrapped handle and another Nandi figurine from India. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

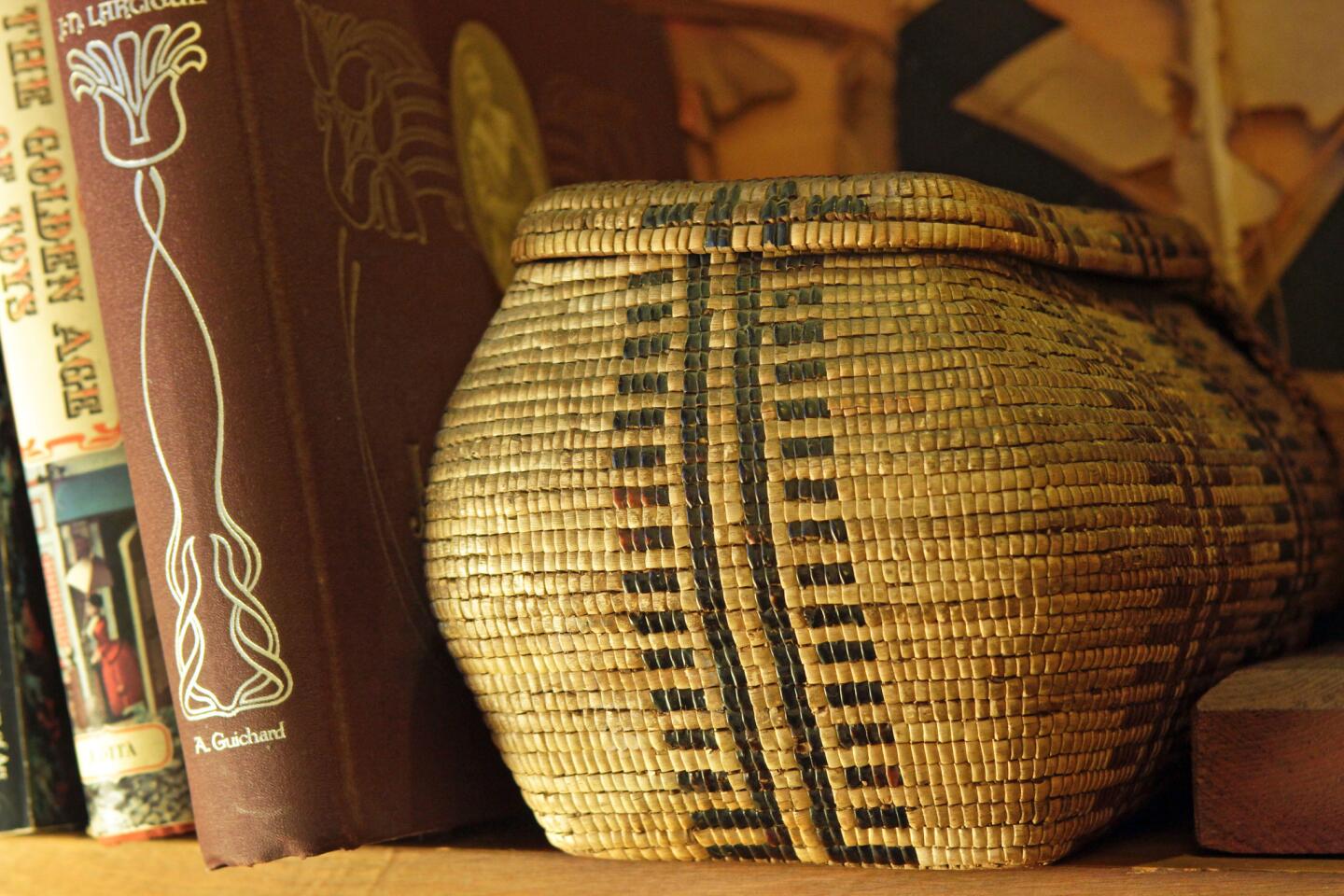

A toy horse on wheels from India and a pillow-shaped basket, possibly from China. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Enamel eye dishes, and … (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

A basket made by indigenous people of Canada. Elsewhere, visitors might seen a wooden spinning toy, a crystal vase or wooden leopard sculptures that arrived courtesy of Billy Wilder. Charles and Ray swapped them for an Alexander Calder mobile. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Limoges plates, and … (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Wooden grasshopper of unknown origin. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Hallway looking back toward the living room. The design echos the Frank Lloyd Wright strategy of using confined entrances as a precursor to voluminous spaces, but the Eames House pushed the concept further with the kind of open floor plan that remains an element of modern living today. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

An alcove off the living room. Though it has been suggested that Charles was responsible for the hard, architectural edges and Ray did the soft interiors, Charles’ grandson Eames Demetrios said the partnership wasn’t that simple. “Charles was trained as an architect, Ray as a painter, but they had a holistic collaboration, where each was the other’s most important sounding board,” he said. “Their collaboration was always blurring the line between technology and art, and their designs flowed from an understanding of the materials and the needs of the user.” (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

In the living room alcove, a feather fan with wrapped handle and another Nandi figurine from India. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

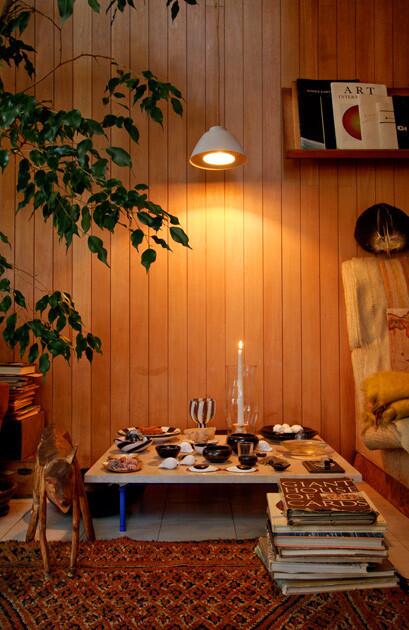

At the time, the couple’s cross-cultural and highly dense approach to decorating was much discussed. The house and its living room was published in numerous popular magazines, including Family Circle. Note the table, which is graced with an eclectic array of objects, including … (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Enamel eye dishes, and … (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Limoges plates, and ... (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

A decoupage book. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Hallway looking back toward the living room. The design echos the Frank Lloyd Wright strategy of using confined entrances as a precursor to voluminous spaces, but the Eames House pushed the concept further with the kind of open floor plan that remains an element of modern living today. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Back in the living room, layered carpets from around the world provide a backdrop to a piece of marble - a de facto tabletop for the simple elegance of a candle, flowers and shell. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

More than 1,500 objects remain in place, the room frozen in time. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)