LAJAS BLANCAS, Panamá — I asked him to state his name and age, instead, he extended his hand, squeezed my arm tightly and responded with a question: “Can you help me recover my child’s body? I’ve been waiting for two months, and nobody tells me anything, help me!”

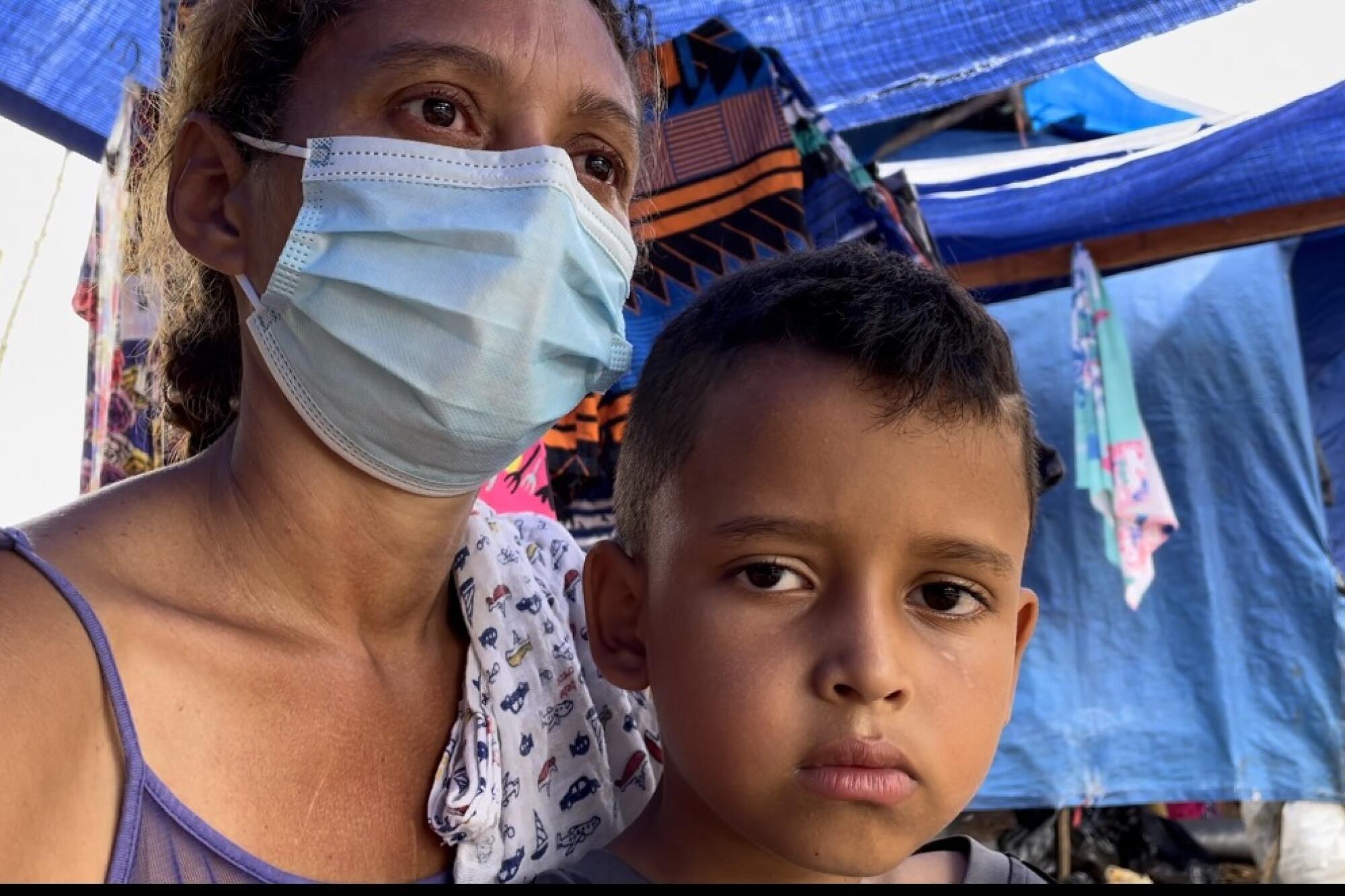

Rosmary Gonzalez, 45, lost her four-year-old son and her husband, 50, while the whole family was trying to cross the Darien Gap jungle, one of the most dangerous migratory routes in the world and the only road connecting South and North America.

The Darien Gap region is so named because it is the only point where the Pan-American Highway, a network of highways linking 14 countries from Chile to the United States, cuts off.

In total, 130 kilometers of dense vegetation, suffocating heat, rivers and swamps are crossed daily by migrants from more than 50 countries coming from regions as far away as Africa and Asia, desperately seeking to reach the United States.

Rosmary left with her husband and three children at the end of July with the illusion of reaching the state of Florida in the United States, where the couple thought they would find work and relief from the poverty and hunger they were experiencing in their hometown Zulia, Venezuela; ironically one of the countries with one of the largest oil and gas reserves in the world.

The $40 monthly budget the family was living on was already unbearable. They sold everything to cover the cost of more than $30,000 to bring the family to the United States. Rosmary never imagined that she would lose half of her family along the way.

It is 10:00 in the morning and the heat and excessive humidity make the days in the Darien area almost unbearable. The mosquitoes relentlessly chase Rosmary and more than 200 other migrants stranded at the Migratory Reception Station in the community of Lajas Blancas, all survivors of the Darien Gap.

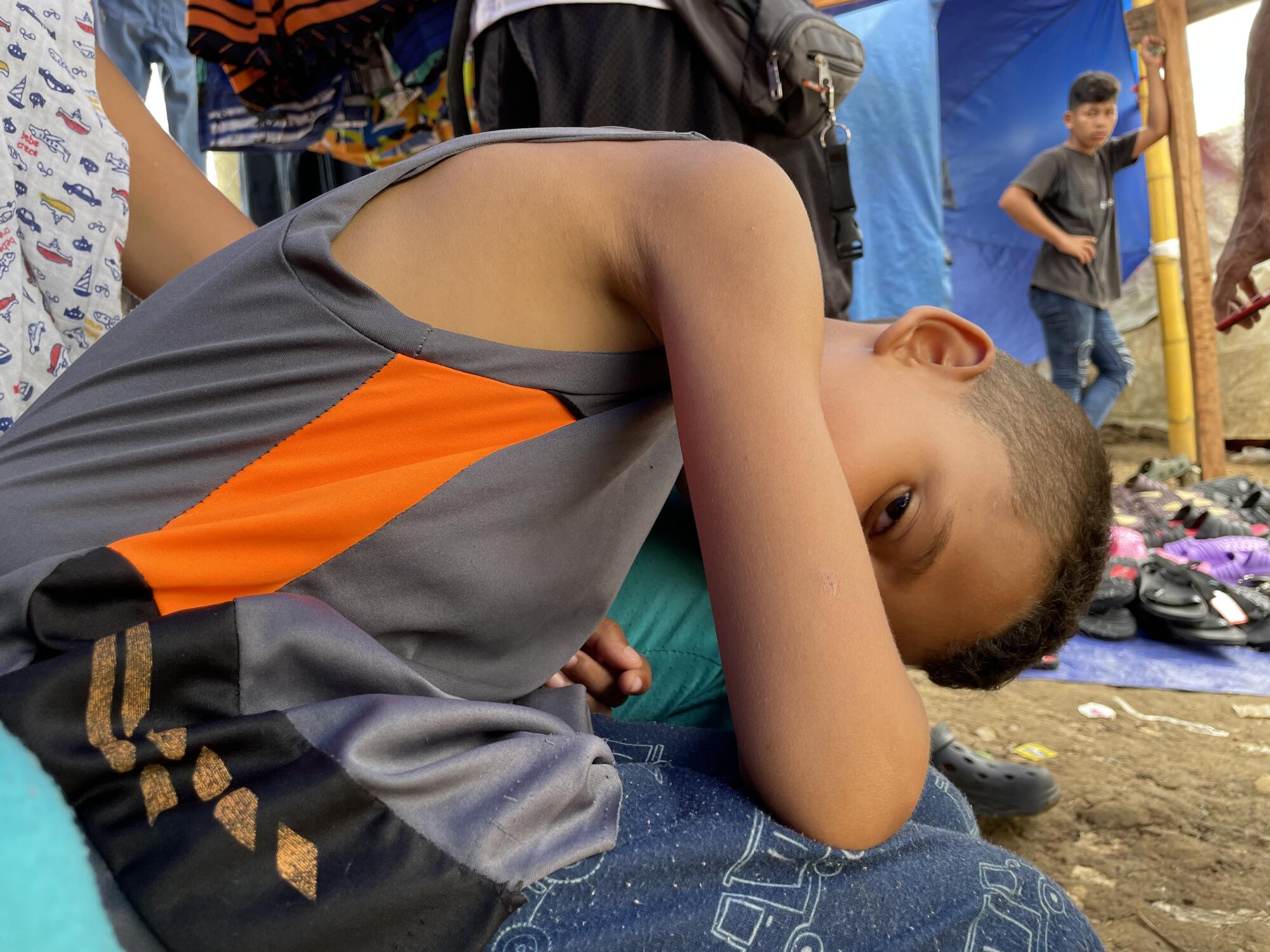

Rosmary’s slender arms gently move to caress Marino, her seven-year-old son who rests on her legs and who, like her, also managed to survive the crossing.

Both are almost thin to the bone. The weight loss has been brutal. The mother wears a purple blouse and plastic sandals, which were given away at the camp, because the so-called “death river” not only took her son and her husband, but also the few belongings they had with them.

“We walked for seven days with our feet knee-deep in mud. My son, the eldest, told me ‘Mom, look at that body over there, look at that body over there,’ and I said, no, no, I don’t want to see anything... When what happened to my husband and my baby happened, it hit me very hard. I never thought that someone in my family would also die,” she says.

She had heard the name “death river” countless times among the caravan of 26 migrants who, along with her, crossed the jungle. Many were afraid of it because they said it was the most complicated passage of the journey.

Rosmary knew firsthand that the nickname was not for nothing. The person who was guiding them, and to whom she had paid $3,000 in advance, did not want to wait until the current went down. The river was raging, recalls the mother.

Several migrants refused to set out and clamored to wait for the river to calm down, but the guide refused to wait any longer; every moment was money lost because other groups were waiting for him.

The line moved deeper into the waters. Rosmary was carrying suitcases. Juan, her husband, carried Daniel, her youngest son, in his arms and Pablo, her oldest son, 16, held Marino. In a stretch of the river, a current caused her to lose her balance and she felt a rush of water completely submerge her. She managed to scream and see how her husband also struggled against the water while holding her son. That was the last image she had of them.

A young Haitian man in the caravan pulled her by the arm, saving her from drowning. When she came to full consciousness, she screamed out the names of her husband and son. Both had disappeared in the current. People from the caravan came to her aid and offered her comfort. In the same group, another man was also crying almost madly. He had let go of his child’s hand who also disappeared under the water... Within minutes, three people lost their lives.

“I only have him and Pablo, my 16-year-old son... I only have them,” she says as he touches Marino’s hair.

Marino has a fever; in less than two hours and he has already defecated six times. Rosmary confesses that she prefers to take him to the bathroom among the dense jungle trees rather than enter the pestilential and flooded bathrooms of the Lajas Blancas migrant camp where she has been waiting since mid-August for the remains of her son and husband.

Along this migratory route, fear is a constant companion. In addition to flash floods, snakes or poisonous insect bites, there are assaults and rapes at the hands of illegal armed groups that control these routes for drug and arms trafficking.

Once they have crossed the Darien, nightmares give way to worse images, the memories of those who were left abandoned in the jungle with broken bones or hallucinating in fever and pain after being bitten by an insect or snake.

“I saw about five corpses in the jungle,” says Jean, a 27-year-old Haitian man traveling with his pregnant wife who was injured on the way while trying to cross the Muerte River.

“I carried my wife, and I could bring her here, but I think of those people who stayed in the jungle. People with broken bones, waiting days for help and no one stops. I saw dead people on the banks of the river, dead in their tents, the body of a girl who passed by me in the river and the screams of pain from the women, I can’t get it out of my head,” he said.

Meat for the vultures

There are four migrant reception stations in Panama, three in the province of Darien, on the border with Colombia, and the fourth on the border with Costa Rica. The four stations house a total of 2,527 migrants, including men, women, boys and girls of Caribbean, African and Asian origin, mostly of Haitian, Congolese, Bangladeshi or Yemeni nationality.

For those who have lost a loved one, these shelters become a bureaucratic limbo. Here, the American dream is transfigured and the desire for a better life becomes a single desire for a miracle, to see their relatives alive again or at least to recover their bodies and give them a dignified burial.

In Lajas Blancas everything has a price: sleeping, drinking water and even sending a WhatsApp is priced at two dollars or recharging a cell phone at three dollars.

The town has stopped subsisting on agriculture and fishing to fill itself with stalls selling food, water and clothing for migrants.

Lajas Blancas is named after some white river stones (lajas) and is territory that also belongs to the indigenous ethnic groups of the Emberá-Wounaan and the Guna Yala.

Some of the Wounaan are hired by the authorities to work in the migrant camps serving food to the almost 500 migrants a day who constantly arrive there.

On the roads of the village, everything smells of humidity, mud, dirt mixed with the smell of firewood and roasted chickens that the residents usually sell to the migrants.

There is no silence, even at night. The rumbling of storms and dogs mingle with the shouts, cries or conversations of migrants wandering through the night.

Everyone in this town knows that the death toll is much higher than the 50 migrant deaths reported this year in the Darien by Panamanian authorities.

It is enough to walk along the paths of the Turquesa River that crosses these lands. There are corpses along the river, it reeks of death, and it is impossible to even identify them after being devoured by the flocks of harpies that fly through these lands or by other animals.

“The harpy is the symbol bird of Panama,” says Neldo, a member of the Wounaan indigenous community with whom we take a boat tour.

The situation in the camps is almost unsustainable, according to international aid organizations. In 2021, 121,737 migrants entered Panama through the Darien jungle, and in just ten months the sum exceeded the amount of the last 11 years combined.

Jean Gough, UNICEF’s regional director for Latin America and the Caribbean assigned to the Darien area, says her teams have never seen so many children crossing and often unaccompanied. “Such a rapid influx of children heading north from South America should be treated urgently as a serious humanitarian crisis.”

Records from Panama’s security minister indicate that 18,000 migrants crossed the jungle last August and one in five were children, most of them Haitian. The total death toll is a big unknown.

Those who survive the Darien are transported in buses by Panamanian authorities to the border with Costa Rica, where hundreds again set out on the road north.

Ahead of them will be more than 5,000 kilometers through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico to reach the United States, the final destination for almost all of them.

From hope to an eternity in hell

Geobaldo is a 42-year-old Venezuelan who lost his six-year-old son. He was traveling with his wife and three little ones. Ivan, six years old, Santiago, two, and Marci, 10 months old.

For two months now, Geobaldo’s routine has been reduced to walking from the camp where he shares a mat with his family to the information station in the hope that there will be news about the body of his little Ivan.

Nightmares torture him, he says. And he can’t get out of his head the terror he felt when the force of the river snatched his son from his hands.

“I carried the older boy and the baby, and my wife carried the girl, but it was too much weight with the baby and the suitcases, and I could not hold my child,” said Geobaldo, who before migrating was an employee of an oil company in his native Venezuela.

Geobaldo dreamed of giving his children a better life in the United States. Of working and saving money to open a restaurant. The force of the river not only took away his son, but also all those dreams.

“In the jungle we lasted seven days with the children and it’s the worst thing I’ve ever experienced. I don’t have the energy to fight anymore,” he says on the verge of tears.

“I would like to scream, to run, to hit. I am desperate... I would give anything to have my son’s body,” he says.

According to UNICEF, since the beginning of this year, more than 150 children have arrived in Panama without their parents, some of them newborns, and at least five children were found dead in the jungle this year, but many bodies remain unrecovered.

Rosmary and Geobaldo have been in limbo for almost two months. The authorities have told them that they are looking for the bodies, but they believe this is a lie.

Rosmary goes out every day to meet new migrants arriving at the camp. She hopes that someone has seen her son. That October morning 580 migrants arrived, according to the authorities’ count.

In the distance, the voices of a group of vendors can be heard talking as they watch a black man lying on the ground and crying loudly.

“His wife died,” says one of the vendors.

Rosmary, seeing the scene in the distance, hears the cries, the comments of the vendors and pauses in conversation.

“That’s how many of us arrived. A Haitian saved my life, but it would have been better to let me die... I feel dead in life,” she says.

Suscríbase al Kiosco Digital

Encuentre noticias sobre su comunidad, entretenimiento, eventos locales y todo lo que desea saber del mundo del deporte y de sus equipos preferidos.

Ocasionalmente, puede recibir contenido promocional del Los Angeles Times en Español.