Tribal bid for federal recognition could pave way for L.A. area’s first Indian casino

A local tribe’s bid for federal recognition is getting a boost from organized labor and a member of Congress who recently introduced legislation that would extend acknowledgement status to the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation and create a 300-acre reservation within Los Angeles County.

The tribe is one of a number of Indigenous groups whose ancestors first populated the Los Angeles Basin and who are seeking the ability to govern themselves on sovereign land. A bill submitted Tuesday by U.S. Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove (D-Los Angeles) would allow the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation to bypass a costly federal petition process that can take a decade or more to complete. It would also allow the tribe to entertain economic opportunities, including building a casino.

If passed in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and approved by the president, up to 300 acres of land acquired and taken into trust by the Department of Interior on behalf of the tribe “will be regulated under the federal Indian Gaming Regulatory Act,” according to the bill.

“Although the excitement is about a casino, for me this is a story about Gabrielino identity and land equity, and an opportunity to right a federal wrong,” said Kamlager-Dove, who serves on the House Committee on Natural Resources.

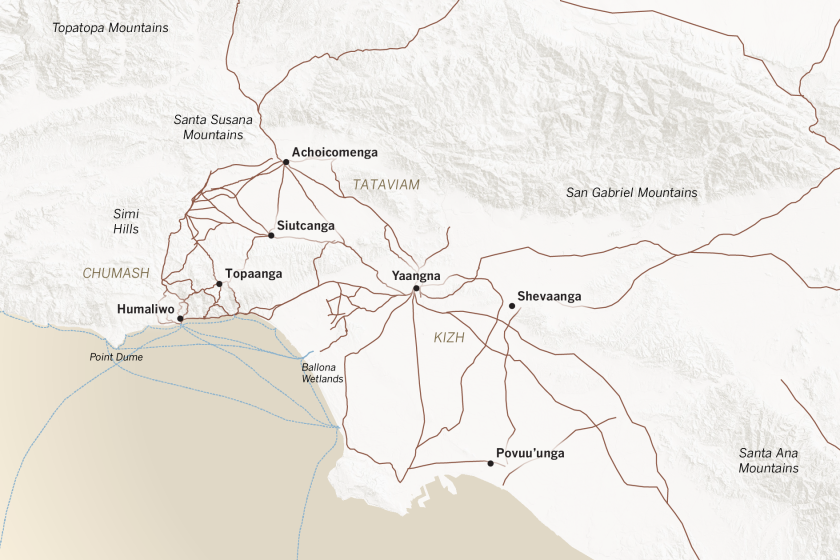

The ‘Mapping Los Angeles Landscape History’ project seeks to illustrate major Los Angeles-area Indigenous settlements.

“This community has almost been denied its ability to exist because it doesn’t have federal recognition, which brings many kinds of protection and support. It has been waiting a long time for this,” she said.

For tribal members, federal recognition represents self-reliance.

“I want to thank Congresswoman Kamlager-Dove for this gift,” said Sandonne Goad, chairwoman of the 700-member tribe. “It’s overwhelming, exciting and full of joy.”

The bill touts support from leaders of the politically influential Unite Here Local 11, a union representing 32,000 hospitality workers in Los Angeles and Orange counties and greater Phoenix.

Unite Here Local 11 officials were unavailable for comment. But Kamlager-Dove said, “I’m really happy about the support from the union.”

The effort is also supported by Sean Harren, president of Teamsters Local 986; Darrel Sauceda, chairman of the board at the Los Angeles Latino Chamber of Commerce; Dolores Huerta, president of the nonprofit Dolores Huerta Foundation; and Pastor William D. Smart Jr., president and chief executive officer of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Southern California.

“What I like about this tribe having a right to build a casino is that it could provide a stable economic future with health benefits, student scholarships and decent homes — and it’s about time,” Smart said.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass was unavailable for comment, but a spokesman offered a statement that did not address the bill directly.

“Los Angeles is home to more Native Americans/Alaska Natives than any other county in the United States and the mayor will continue to lock arms with the tribes, as we all work together to fight to make Los Angeles better for all,” said Zach Seidl, deputy mayor of communications.

Wild animal rehabilitation organizations claim California officials are hassling their operations after decades of cooperation. The state denies it.

Making the tribe’s reservation dreams become reality won’t be easy. The bill will need bipartisan support in a divided Congress, and any proposal for significant development such as a full-scale casino complex would face the concerns of local governments and surrounding communities.

“I hope there’s no pushback, but I know there will be,” Goad said. “We will prevail no matter what comes our way.”

The stakes are high. A federally recognized tribe has sovereignty, does not pay taxes and is exempt from following state or county legal ordinances. It is entitled to full service from local law enforcement authorities and fire departments, hospitals, and road and flood control systems.

It is also eligible for federal assistance from legal programs created to help reclaim lands lost over the decades through tax sales, fraud and violence, and with healthcare, education and protection of sacred sites.

For the state’s federally recognized tribes that do own large casinos, particularly those within easy driving distance of major cities, gambling has yielded an enormous payout, allowing them to use their growing clout and the legal authority of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act to take back remains and artifacts held by museums and universities for proper care and burial.

Today, the industry that began just three decades ago as a handful of bingo parlors has mushroomed to include 85 Indian casinos across California — businesses that provide 124,000 jobs and add about $19 billion to the state economy annually, according to the American Gaming Assn.

Indian casino sites said to have been under consideration in Los Angeles County over the last two decades have included a downtown parcel, a former dump in Monterey Park, property in Compton, and Hollywood Park in Inglewood.

Before any of that could take place, however, a tribe would have to take the land in question into trust as sovereign Indian territory. No Native American group in the county has done this.

After two mountain lions who were transplanted to the Mojave Desert died of starvation, California wildlife officials have revised their relocation policy.

In 2001, then-Rep. Hilda Solis sponsored legislation asking Congress to extend recognition to a different Gabrielino group in Los Angeles County. But the bill was “shelved during the 9/11 crisis,” said Wallace Cleaves, a member of the Gabrielino/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians.

Some say it never resurfaced because of intertribal conflicts among more than five Gabrielino factions, including some wanting to build casinos.

Kamlager-Dove’s bill has already generated a backlash from several Gabrielino groups who feel more deserving of recognition.

In an interview, Goad suggested a solution almost certain to trigger more controversy.

“Those others can join our tribe,” Goad said. “We’re already processing 250 applications” for membership.