Newsom wants to waive environmental rules in the delta amid drought worries

As January’s drenching storms have given way to an unseasonably dry February, Gov. Gavin Newsom is seeking to waive environmental rules in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta in an effort to store more water in reservoirs — a move that is drawing heated criticism from environmental advocates who say the action will imperil struggling fish populations.

In an executive order signed Monday, Newsom directed the State Water Resources Control Board to “consider modifying requirements” for California’s two water conveyance systems in the delta, the State Water Project and the federally operated Central Valley Project.

“While recent storms have helped replenish the state’s reservoirs and boosted snowpack, drought conditions continue to have significant impacts on communities with vulnerable water supplies, agriculture and the environment,” an announcement of the order read. “Until it is clear what the remainder of the wet season will hold, the executive order includes provisions to protect water reserves.”

As part of the governor’s effort, the state Department of Water Resources and the federal Bureau of Reclamation have submitted a petition to state water regulators seeking an “urgent, temporary change” in water-quality and outflow requirements in the delta “to ensure the availability of an adequate water supply while also ensuring protection of critical species and the environment.”

California officials are touting a $2.6-billion deal to boost the health of a vital watershed, but environmentalists are calling it a backroom scheme.

The agencies are requesting an easing of requirements that would otherwise mandate larger flows through the estuary. The aim is to hold back more water in Lake Oroville while also continuing to pump water to reservoirs south of the delta that supply farmlands as well as Southern California cities that are dealing with the ongoing shortage of supplies from the shrinking Colorado River.

“In Oroville, we want to conserve storage, and south of the delta in state-managed reservoirs, we want to build up storage,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the state Department of Water Resources.

The extreme weather swings over the last two months make this approach necessary, Nemeth said. This approach “provides flexibility for water supplies” if California stays dry in the coming months and achieves a “balance” in managing water while protecting the environment, she said.

Environmental and fishery advocates condemned the state’s approach. They say it will be harmful for such species as Chinook salmon, longfin smelt and endangered delta smelt.

“We are watching the demise of our native fish and wildlife in the delta in real time,” said Doug Obegi, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “And it’s these kinds of decisions by the governor and the State Water Board to waive the rules, the rules that we already know are inadequate, that are leading inexorably toward this ecological crisis in the delta.”

Obegi, along with leaders of The Bay Institute and San Francisco Baykeeper, wrote to the State Water Board last week expressing alarm that state and federal agencies were about to violate minimum flow requirements in the delta.

They were referring to requirements for sufficient flow to keep the saltwater-freshwater boundary near a western point in the estuary after high-flow events, such as the torrential rains in January. The requirements, part of 1995 water-quality standards, call for enough flows through the estuary to keep salinity at levels that benefit fish including longfin smelt and delta smelt.

Obegi and the other delta advocates wrote that this requirement aims to ensure “a more natural outflow pattern of a gradual decline from a peak flow” to prevent declines in fish populations. And they said state and federal agencies have been violating those requirements since Monday.

“Why do we have rules if we’re not going to actually follow them?” Obegi said.

About 95% of the water that flowed into the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta in the first two weeks of January ended up in the Pacific Ocean. Here’s why.

Obegi said the Newsom administration is effectively giving a “get-out-of-jail-free card to allow the state and federal water projects to steal the environment’s water” and send much of it to the agriculture industry in the Central Valley, along with cities.

He argued that state officials decided to waive the rules and “gut the environmental protections” after facing pressure from legislators and others who called for loosening restrictions in the delta to free up water supplies.

Nemeth denied that, saying her agency is seeking relief from meeting the salinity requirement at the western location near Port Chicago because officials believe other existing protections are adequate.

“There is a way to protect species absent this requirement,” Nemeth said in an interview. “If there are ways in which we can continue to protect the environment but are less costly in terms of water supplies, that’s how the department would like to balance, given where we are in our current drought conditions.”

By not having to release more water from Lake Oroville, Nemeth said, “we can continue to grow storage from snowmelt into the reservoir.”

Officials at the State Water Board said they are reviewing the petition and that the board’s executive director will decide on the request within the next week.

State regulators have approved similar previous petitions to waive water-quality requirements in the delta during drought years from 2014 to 2016 and in 2021 and 2022.

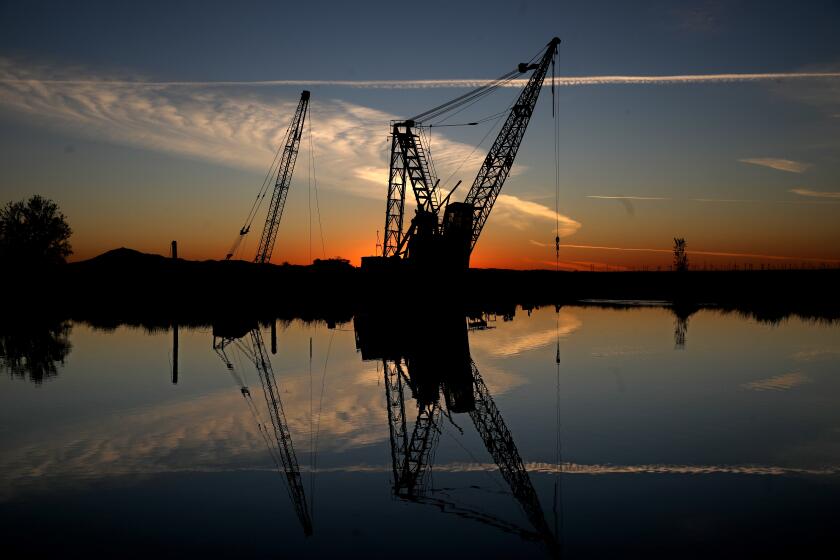

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is formed by the convergence of California’s two largest rivers and lies at the heart of the state’s water system. The delta’s fragile ecosystem has been deteriorating for years, with demands for water taking a toll on the environment.

“This comes at a time when our salmon stocks have been clobbered,” said John McManus, president of the Golden State Salmon Assn.

The last three years of severe drought have been particularly devastating for salmon, and recently low numbers of adults have returned to spawn, McManus said.

“There is fear up and down the coast, and beyond, that we may not have a salmon fishing season this year because of the poor condition of our salmon stocks,” McManus said.

As the state gets drier, and wildfires climb to higher elevations, snow is melting faster and earlier than before — even in the middle of winter.

This is the time of year when juvenile salmon are swimming downstream, he said, and they rely on the flow through the delta to help push them to San Francisco Bay.

“At the very time of year when they need outflow the most, here comes Gavin Newsom basically telling state water managers that they can cut the outflow,” McManus said.

State officials said Newsom’s order is aimed at protecting water supplies amid climate-driven extremes. The governor said in the order that the extreme swings in recent months point to “an overarching need to continually reexamine policies to promote resiliency in a changing climate.”

In addition to the measures in the delta, the governor ordered state agencies to expedite permits for projects that will capture stormwater runoff and recharge groundwater.

Newsom kept in place existing drought measures and ordered agencies to make recommendations on further actions by the end of April, including the possibility of lifting any emergency measures that are “no longer needed.”

How to divide Colorado River cuts: A breakdown of how California’s proposed water reductions compare with an offer submitted by six other states

The state’s reservoirs have risen dramatically after the storms in January. The Department of Water Resources recently announced that water suppliers will probably receive 30% of their full allotments from the State Water Project, up from an initial allocation of 5%.

Lake Oroville is now at 69% of its capacity, an above-average level, and other reservoirs have similarly risen.

California’s snowpack in the Sierra Nevada measures 186% of average for this time of year.

Critics of the governor’s action questioned how the current situation can be interpreted as a “water emergency.”

“Newsom is encouraging state agencies to consider waiving even the inadequate water rules we have — for the third year in a row — in order to increase water diversions to Central Valley agribusiness,” said Jon Rosenfield, science director for San Francisco Baykeeper. As the state continues to waive protections, he said, “some species that have lived in the Bay for millennia will pay the ultimate price.”

The endangered delta smelt population has declined to low numbers in the wild. Obegi said he’s concerned that state data show 20 delta smelt — a high number — have been “salvaged,” and presumably killed, at the pumps this month.

State and federal water agencies, however, conducted a biological review and concluded that waiving the requirements “will not result in unreasonable impacts to fish and wildlife.” The California Department of Fish and Wildlife agreed.

The governor’s order allows the state to maximize water supplies north and south of the delta while protecting the environment, said Lisa Lien-Mager, a spokesperson for the California Natural Resources Agency.

“These actions reflect the need to create as much flexibility as possible to safeguard water supplies after three historic dry years and uncertainty today about how the rest of the wet season will unfold,” Lien-Mager said. “Californians expect us to take every action possible to protect our long-term water reliability while balancing the need to protect fish and important aquatic habitat.”

Citing global warming, California Gov. Gavin Newsom has unveiled a new water strategy to conserve, capture, recycle and desalinate supplies.

The State Water Contractors, an association of 27 agencies, supported Newsom’s order. The agencies receive water under contract from the State Water Project for farming areas or cities.

“We must be nimble in ensuring responsible water management for both water supply and the environment,” said Jennifer Pierre, the association’s general manager. She said many of California’s current regulations, including the delta salinity and outflow requirements, “do not reflect the climate whiplash we are now experiencing.”

Pierre said the state’s approach is an “appropriate action to help realign California’s water management decision-making.”

The delta isn’t the only region of California where a decision about river flows is provoking controversy. The Bureau of Reclamation announced this week that it is reducing flows from Northern California’s Iron Gate Dam into the Klamath River by about 11% to “address limited available water supply” and risks for fish species including shortnose and Lost River suckers and coho salmon.

Leaders of the Yurok and Karuk tribes said they are concerned the decrease in flow will affect coho salmon eggs and put the fish at risk.

Tribal leaders recently celebrated the federal approval of plans to demolish four dams on the Klamath River, calling it a positive step for the government to move toward meeting its obligations to the region’s Native people.

“Dam removal will dramatically improve water quality and restore salmon access to hundreds of miles of historical habitat,” Karuk Tribe Chairman Russell “Buster” Attebery said. “But if the bureaucrats at Interior have their way and deny salmon adequate flows for spawning, the dam removal effort will be fruitless and the sad history of colonization and genocide will continue for another generation.”

Karuk Councilmember Arron “Troy” Hockaday said the water savings “will make it more likely that irrigation deliveries will be available to water users.”

“This has more to do with potatoes than it does fish,” he said.