California is turning mountain lions into roadkill faster than they can reproduce

In the last eight years there have been 535 mountain lions reported killed on California highways — a steady toll of one to two each week that scientists suggest may exceed the reproductive rate of increasingly isolated and inbred puma clans.

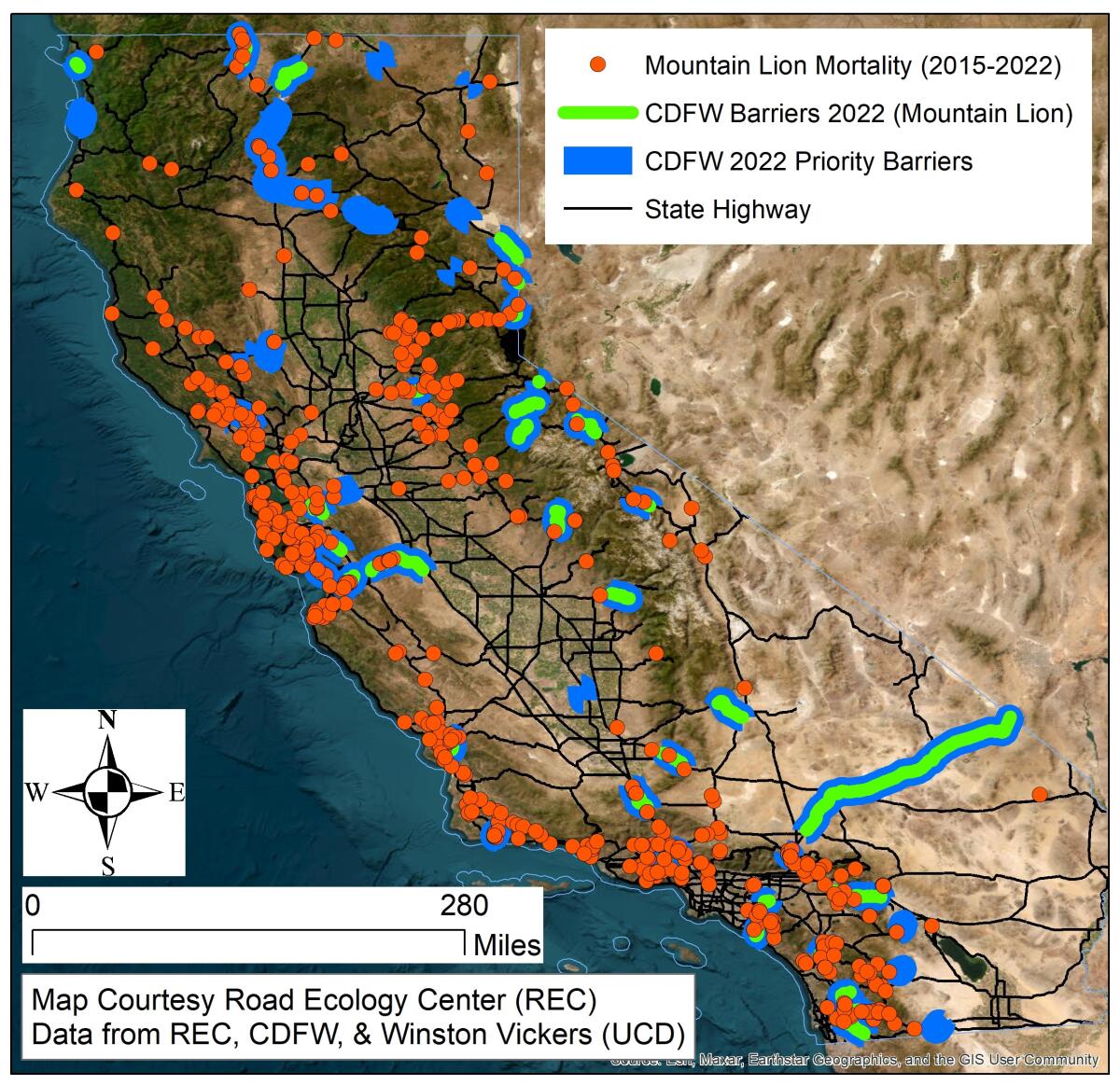

“We may have reached a critical threshold: mountain lions getting killed by cars faster than they can reproduce,” said Fraser Shilling, director of the road ecology center at UC Davis, who on Thursday released a statewide map of the lethal collisions between 2015 and 2022.

“Southern California is the undisputed capital of freeways and car culture,” he said. “But state highways have turned out to be a dead end for mountain lions.”

The desert tortoise is teetering on the brink of extinction. Can California’s Endangered Species Act save it from oblivion?

To produce the map, Shilling said, mountain lion strike data were collected from CHP, Caltrans, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, UC scientists and others and merged into a geographic information system for visualization.

Most of the vehicle strikes were clustered along stretches of highways and freeways that reach out beyond major population centers including Southern California, the Central Coast, the Bay Area, and the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada range.

Overall, however, the annual number of roadkills involving mountain lions — except for 2020 when traffic was unusually low because of coronavirus stay-at-home orders — has shown a slight downward trend, while the amount of vehicle traffic remained unchanged, Shilling said.

For instance, in 2022, 77 mountain lions were reportedly killed by vehicles, compared with 92 in 2017, Shilling said.

“Those numbers could suggest that the fewer mountains you have in a given area, the less likely it is to hit one,” he added. “In any case, every time one dies on the road we’re repeating the tragedy of P-22.”

The legendary mountain lion known as P-22 roamed the hills in and around Griffith Park for more than a decade until he was hit by a vehicle and found injured in a Los Feliz backyard. State officials decided to euthanize P-22 on Dec. 17 because he was suffering from numerous health issues.

P-22 had braved a 20-mile odyssey to get from the Santa Monica Mountains to Griffith Park. The cat’s route took him over concrete and backyards, through culverts and across commuter traffic on the 405 and 101 freeways.

Free tickets for a Feb. 4 celebration of life honoring P-22 at Griffith Park’s Greek Theatre were all claimed within just a few hours after the reservation window opened.

Vehicle strikes, rat poison, inbreeding, urban encroachment and wildfire are all contributing to a dire prognosis that scientists call an “extinction vortex.” There’s an almost 1 in 4 chance that the charismatic cats could be extinct in the Santa Monica and Santa Ana mountains within 50 years.

The snowy owl is a North Pole native but appeared around Christmas Day in Cypress and hunkered down on the rooftop of a house.

The carnage that is plaguing mountain lions and other wildlife — and is now causing state transportation officials to rethink future development plans — started long before Los Angeles became known for its spiderweb freeway systems.

The first historical record of roadkill in California came from Joseph Grinnell, of UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, in 1920, when he became alarmed “by the number of dead animals of various sorts on the road.” He was driving a Model T Ford through northern Los Angeles County’s Soledad Pass.

“This is a relatively new form of mortality,” he wrote, “and if one were to estimate the entire mileage of such roads in the state, the mortality must mount into the hundreds and perhaps thousands every 24-hours.”

Flash forward 103 years, and crashes with wildlife are prompting calls for a variety of projects designed to reduce fatal collisions while helping animals such as bears, elk, deer, bighorn sheep and mountain lions cross dangerous highways to find food and mates.

Mountain lions are not endangered in California, but in the Santa Monica Mountains, the 101 Freeway exists as a near-impenetrable barrier to gene flow for a group of about 10 of the predators. In the Santa Ana Mountains, the 15 Freeway restricts the movement of a family of about 20 cougars.

Winston Vickers, a veterinarian at the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center, said, “a big worry has always been that the impact of cars combined with other sources of mortality can be a threat to mountain lion survival, especially if a population is declining genetically.”

Shilling’s survey comes at a time of ongoing efforts by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to identify and prioritize wildlife movement barriers across the state and develop plans for wildlife crossings.

Among them is the $87-million Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing currently under construction over a 10-lane stretch of the 101 Freeway near Liberty Canyon in Agoura Hills.

Other dangerous stretches, according to Shilling and state wildlife authorities, include Interstate 5 over the Tehachapi Mountains north of Los Angeles, Interstate 15 near the Riverside County city of Temecula, State Route 91 in Orange County, State Route 74 through Riverside County’s Santa Rosa Mountains, and Interstate 8 in San Diego County.

Gov. Gavin Newsom a year ago signed the Safe Roads and Wildlife Protection Act into law, which received bipartisan support and requires Caltrans to identify barriers to wildlife movement and prioritize crossing structures when building or improving roads.

For Shilling, such improvements can’t come soon enough. “We basically have given up on the idea of protecting wildlife if it costs us the ability to drive,” he said.

The big question now, he suggested, is this: Are we willing to do enough to protect the creatures that also have homes in California?