Remnants of the salt evaporation process can still be seen in thousands of acres of altered wetlands along San Francisco Bay. (Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

SAN JOSE — Standing on the edge of a repurposed marina, at the end of a long wooden walkway that harked back to more prosperous times, Brenda Buxton took in the disorienting landscape.

Directly before her were the remnants of an industrialized, salt-encrusted pond that stretched for what felt like miles. Here along the southernmost edges of San Francisco Bay, the water glimmered a strange tinge of red. Its flatness belied the threat of rising seas.

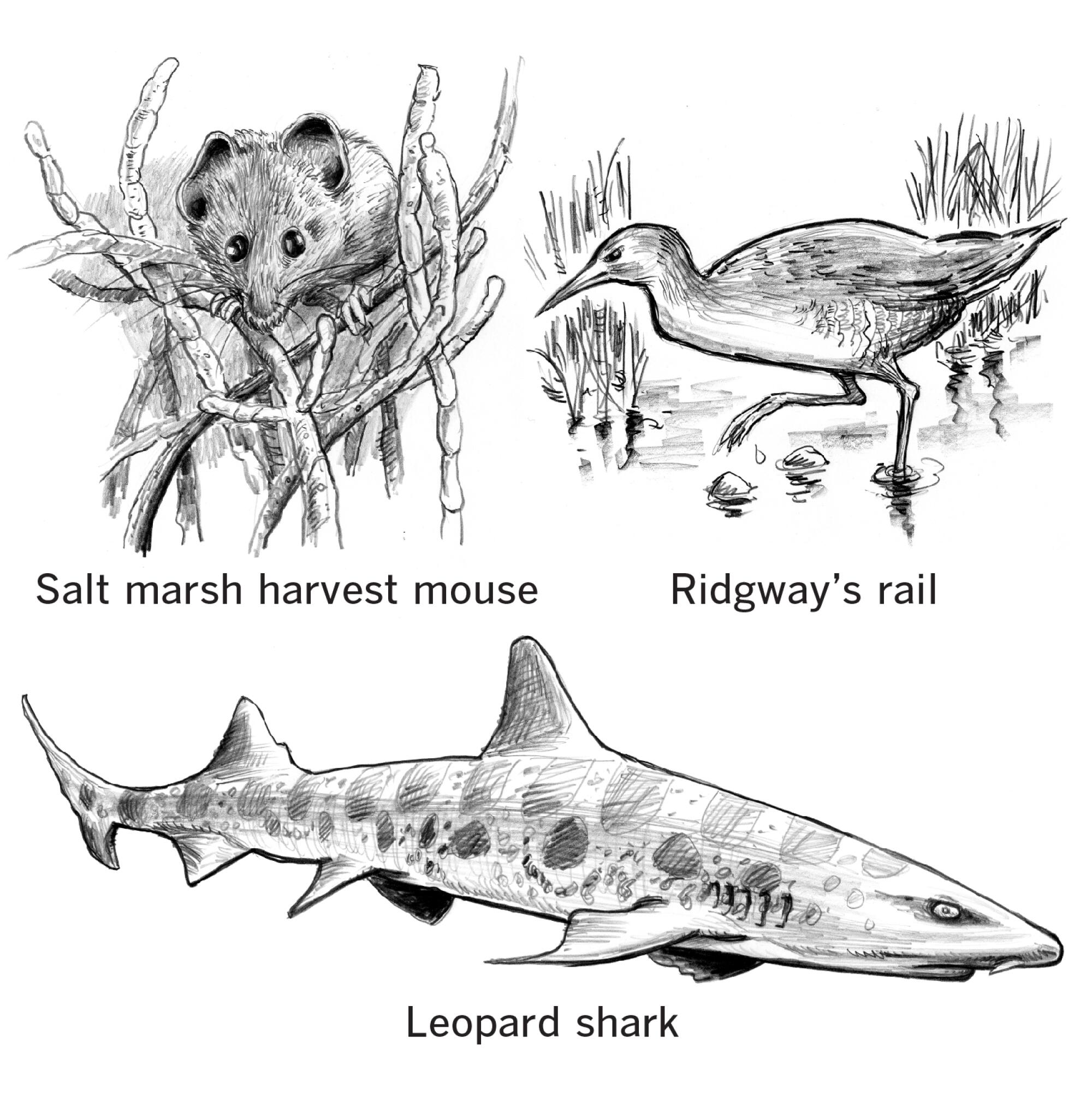

She scanned the horizon for signs of wildlife and envisioned the wetland she wished she could see instead: sweeping acres of marsh grass swaying gently with the breeze. Thousands of shorebirds and a special red-bellied mouse that exists nowhere else in the world. She could almost smell the slightly earthy air of this once-muddy shoreline resetting each day with the tide.

It’s painful, Buxton finally said out loud, to realize just how long it can take to revive ecosystems left so ruined but critical to our survival.

Therein lies the crux of the largest, most ambitious tidal wetland restoration project west of the Mississippi, an effort that has gone on for so long that most people today have forgotten it exists.

Saving a vanishing marsh — while also figuring out what to do with a community that would drown if its existence continued to be overlooked — takes decades if not generations, costs hundreds of millions of dollars and requires the ability to think so long-term and so large-scale that every step seems unprecedented.

Buxton may never see the full fruits of her labor, but the vision she has helped set in motion could ultimately reframe how California adapts to sea level rise. If done right, this multilayered effort to rebalance the land would pave the way for even more imaginative projects that seek to build with nature rather than against it.

“There are a lot of creative ideas out there, but the question is: Can we get them in the ground fast enough?” said Buxton, who has dedicated much of her life to the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. “We only have so much time left before it’s too late.”

::

A bird flies over tracings of tidal channels that used to meander through this historic marsh, which has been trapped for decades as a manmade salt evaporation pond. (Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

It’s hard to imagine today, but before this part of the Bay Area became a land of shimmering tech campuses and political prestige, its claim to fame was predominantly salt.

Salt was the true gold that put San Francisco on the map, and the South Bay, with its reliably warmer climate, turned out to be perfect for harvesting the mineral. The native Ohlone people knew this and had gathered, for thousands of years, the evaporated crystals that would form on the uppermost edges of the region’s vast and vibrant marshlands.

California’s earliest settlers were quick to capitalize on this wisdom in the 1850s. Salt, in addition to preserving food, is a critical ingredient for mining, canning, bleaching paper — even refining gasoline. Sodium chloride also kickstarted the modern chemical industry and made possible the chlorine needed to treat sewage and purify drinking water.

To speed up evaporation, one saltmaker built a big, shallow pond and used pumps and tidal gates to control the flow of seawater. Others followed suit, diking more wetlands into pond after manmade pond. The water turned shocking hues of reds, pinks and greens as different microorganisms latched onto the saltier environment. Fly over San Francisco today and it’s hard to miss the surreal-looking patchwork of magenta and lime-green water — a vivid display of how the shoreline became one of the largest salt evaporation complexes in the world.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

But it is also thanks to salt that thousands of acres of tidal marsh were never paved over. Because salt made so much money, there was little incentive to build expensive housing or more complicated infrastructure — a fate that befell most other wetlands in California.

About 90% of the state’s marshlands, in fact, have been choked, drained or filled to accommodate development. A study led by the U.S. Geological Survey found that salt marshes along the West Coast could disappear entirely in less than a century.

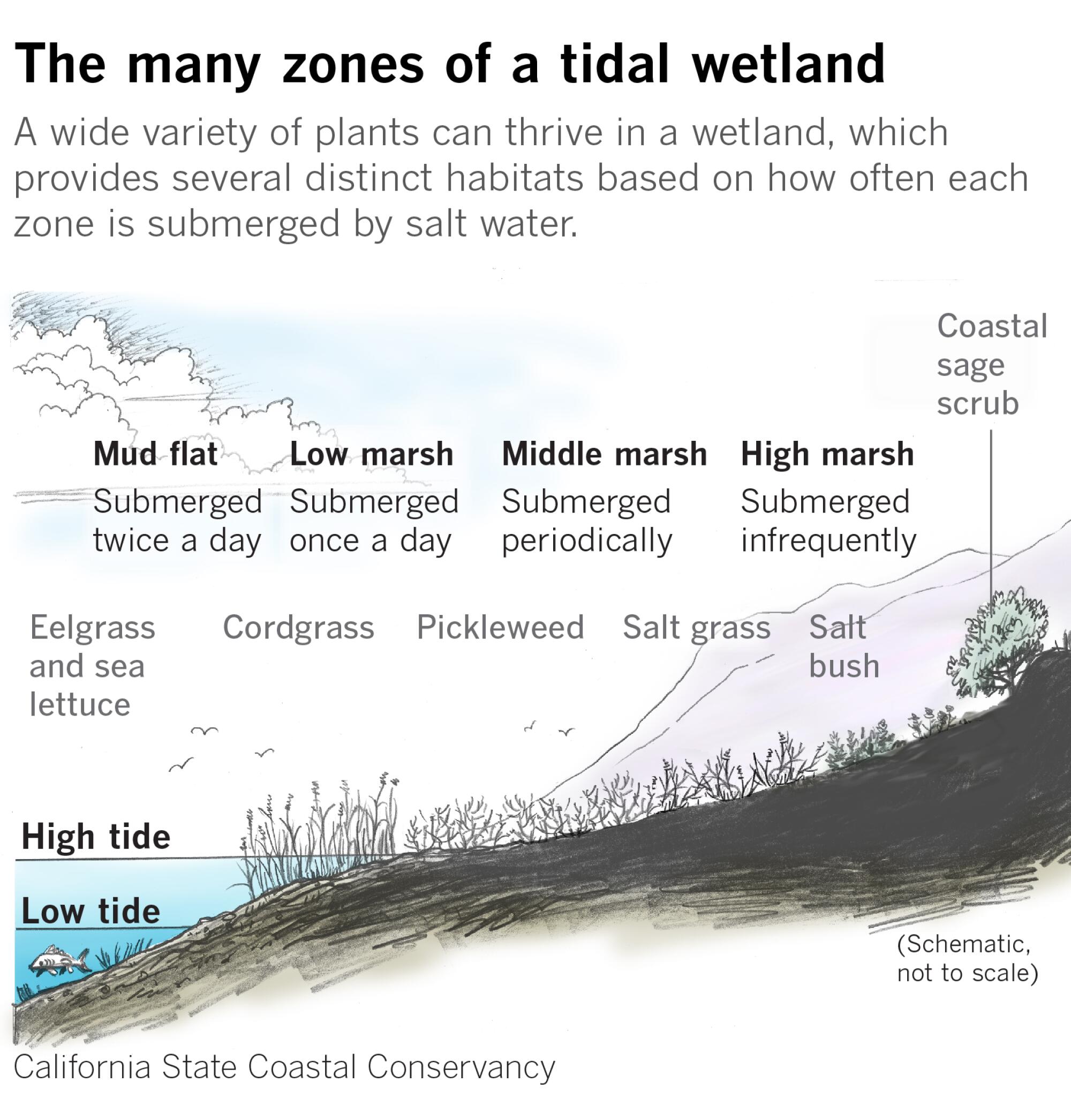

Not quite land and not quite sea, tidal marshes serve as a refuge for migrating fish and a remarkable array of wildlife.

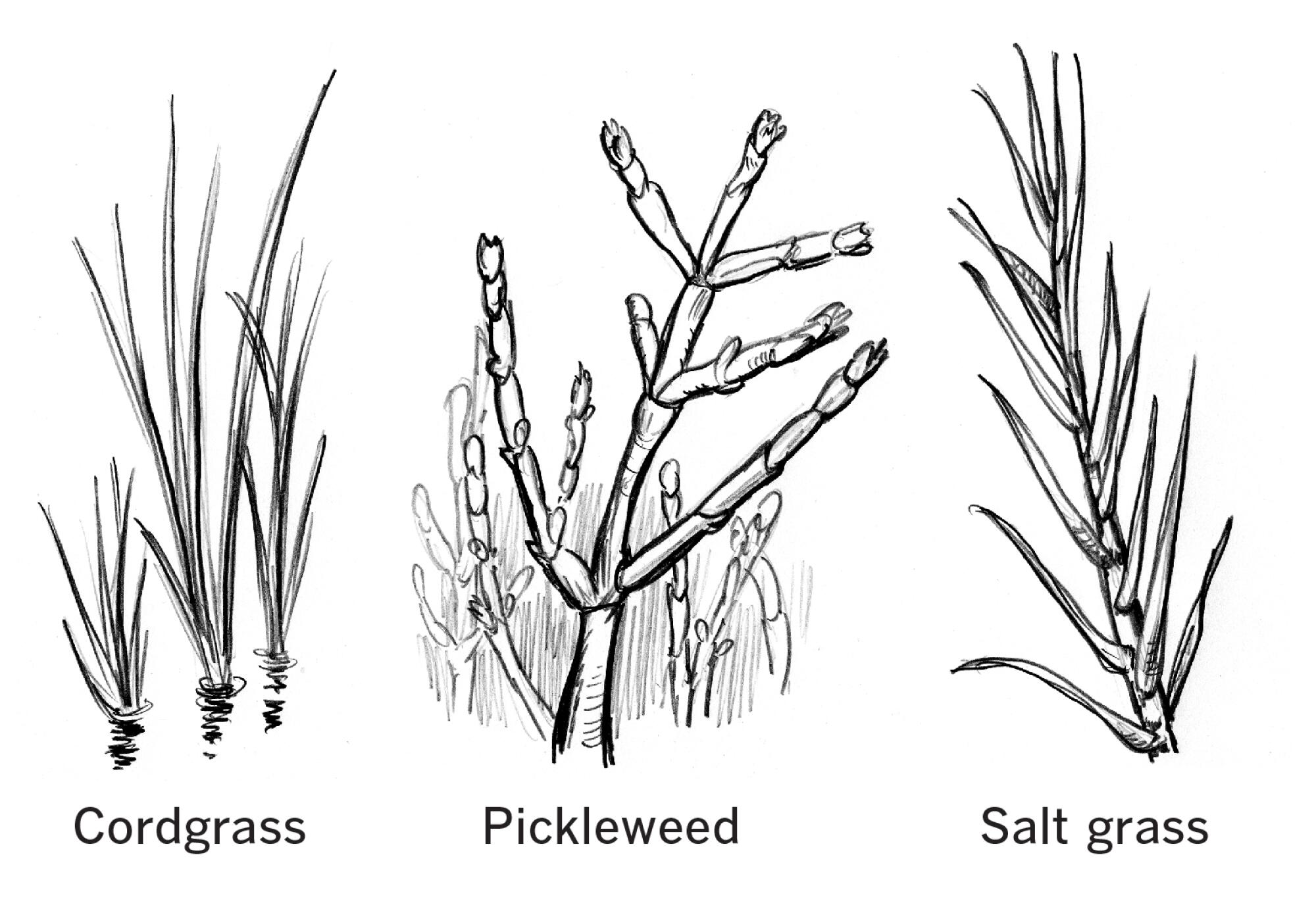

These muddy ecosystems also help stabilize shorelines by absorbing floodwaters like a sponge. They filter polluted runoff before it flows into the sea, and their pickled, half-submerged plants play an outsized role in putting more oxygen into the air.

They are also extraordinary when it comes to sequestering planet-warming gases: Studies show that coastal wetlands, left to their own devices, can capture and store three to five times more carbon dioxide than tropical forests — sometimes much, much more.

The pressure to revive as many wetlands as possible has been mounting for decades, and it became clear that the salt ponds — the last uncluttered stretch of San Francisco Bay — were a strategic place to start. Federal wildlife officials began by acquiring 13,000 acres from Leslie Salt Co. in the 1970s and preserving the open space as the first urban wildlife refuge established in the United States.

“It took a grass-roots effort, a community coming together that said that conservation didn’t have to just exist up in the mountains or in the wilderness — that it can be done in an urban landscape,” said Matt Brown, who manages the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

In the following decades, officials continued to cobble together funding to purchase more salt ponds from Leslie and its successor, Cargill. Then in 2002, in a deal worth $243 million and shepherded by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), Cargill agreed to sell more than 15,000 acres.

Re-creating a swath of former wetlands larger than Manhattan has turned out to be far more challenging than imagined.

Restoring the marsh is the straightforward part, said Buxton, who took on this task decades ago for the California State Coastal Conservancy. “You breach the berm, the water comes in and then five, 10 years later, the mud builds up to the right tidal elevation, the pickleweed comes back, the spartina comes back — and a few years later, after the plants have established, the animals show up. … Marshes make themselves.”

But getting to this last step, where nature can finally finish the job, has been one uncharted step after another. Officials tested their plans with a few ponds at Eden Landing and Ravenswood, two nearby nature preserves. Each berm breached was a victory, but everyone knew what the real game changer would be: the nearly 3,000 acres of former wetland fronting the community of Alviso.

Buxton, to explain this final piece of the puzzle, did an about-face and turned her back to the water. A single road sloped downward toward the flood-battered neighborhood, where abandoned canneries and weathered homes clustered together.

“You go from the water down into the town,” she said, noting how Alviso, sitting more than 10 feet below sea level, fills up like a bowl whenever it floods.

Simply breaching the salt ponds would drown this already beat-down town, and the Sophie’s choice loomed large: Was it possible to save both Alviso and a much-needed marsh, or must this entire community be sacrificed?

::

A once lively seaport, Alviso served in the mid-1800s as the gateway to Santa Clara Valley. Nestled before a plain of half-submerged marsh grass, beneath abundant skies filled with migrating fowl, this burgeoning little community was even home to California’s first governor.

But when railroads became the transportation of the day, Alviso got snubbed. No longer a critical hub for anything, the town eventually became a landing place for Chinese, Japanese and Portuguese immigrants who built up their lives in the canneries. Filipino laborers, Dust Bowl refugees and Mexican braceros also made this weary place home.

Santa Clara Valley, which later became Silicon Valley, continued to grow at the expense of this bypassed town. Farmers pumped so much groundwater out of the land that Alviso began to sink. Flooding haunted residents as the ground dropped below sea level.

Aerial images from past floods show the town so inundated that only the roofs of homes could be seen above water.

San Jose, which annexed Alviso in 1968, also turned its back on the community. The city planted its sewage treatment facilities by the shore and used one end of town as a garbage dump. Residents had been promised street paving, fire protection and much-needed storm drains in exchange for consolidation, but decades later, many say Alviso still feels like an afterthought.

“We’ve always been the dirt underneath the shoes of San Jose. … When you say the word Alviso, people are like, ‘Oh, that’s the place that stinks’ or ‘You live in ghetto town,’” said Jozette Galvan, whose grandfather, a field worker, and father, a construction worker, helped build up the community. “It’s only ghetto if you see it that way. Alviso has always been great — it’s humble, everybody knows everybody. … My uncle, my aunts, my cousins, we’re all still here.”

These inequities have given the wetland movement some pause. Relocating longtime families like Galvan’s — a logical move if you were designing purely from an environmental perspective — was a moral and costly dilemma.

“A lot of people had the idea of just buying them out and restoring the whole area. But they’re here, this is their community — they’ve remained even after they’ve been flooded so many times,” said Rechelle Blank, chief operating officer at Valley Water, the agency in charge of flood protection for Santa Clara County. “It’s a very tight community, and they’ve built themselves up.”

With some unconventional engineering and a bit of compromise, it seemed possible to do it all. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, whose age-old tactic was to fortify a shoreline with concrete, had to come around to the feasibility of also accommodating nature. Officials finally came up with a plan to construct a special four-mile-long levee out of dirt that would not only protect the town but also enhance the marsh.

The levee, they reasoned, would protect Alviso’s 2,500 residents from the water that would flush in once the ponds were breached. It would also spare a sewage treatment plant and a water purification center that serve more than a million people in the region. Companies like Hewlett-Packard and Google were moving into Alviso, making the economic case for flood protection even greater.

As for the marsh enhancement, a long and gradual dirt slope — extending many hundreds of feet — will be added to the bayside of the levee to give the wetland different elevations to evolve. Conservancy and wildlife officials have been designing each section of the slope, known as an ecotone, so that mud flats, middle marsh and a variety of upland habitats can take root. A bike and walking trail will run along the top of the levee, providing more access to nature for the entire region.

The estimated cost at the time, in 2015, was $174 million. But it took years to obtain the necessary permits, and even more years to truck in enough dirt for the levee. There was also some back-and-forth on how high the levee should be: The Army Corps, which had never had to incorporate future threats of sea level rise into a design, said 12.5 feet would be sufficient based on existing conditions. Other agencies insisted it needed to be 3 feet higher and quite a bit wider.

By the time the project team finally secured a construction bid for the bigger levee, in 2021, the bill had more than tripled — to a staggering $545 million.

Cobbling together the extra funds has sacrificed even more time in the race against sea level rise. Many are now turning to the federal government. Some have also started to question whether big tech companies should help foot the bill. A $61-million boost came from a conservation tax, known as Measure AA, that a group of Bay Area leaders had crafted in 2016 to help fast-track local wetland projects.

Back on the banks of the salt pond in Alviso known as A12, on a windy autumn day last year, Buxton — who has worked for the state conservancy since the 1980s — recounted the latest numbers and joked about her gray hair. Plans were finally underway to build at least 1.6 miles of the four-mile levee with the money they had, but there was still no groundbreaking date.

Buxton wasn’t quite ready to say it, but she was finally retiring. She had really wanted to see this project to the end, she said, but when she saw the new construction timeline, she couldn’t help but think, “I’m not going to be alive for this.”

She apologized for her morbid humor, but she’s been thinking a lot lately about time.

Getting the details in order has gone on for so long that an entire generation of people in the Bay Area know almost nothing about the salt ponds. Those in high school and college today weren’t even born when California took on such an immense vision.

The good news, Buxton said, is that future projects will at least have a case study to turn to. There will never have to be another unprecedented restoration in the state that takes this much time to figure out.

She’s still holding out hope she will one day see this flattened landscape teeming with marsh life. Shorebirds, no longer endangered, will be pecking at the exposed mud during low tide. The long, sloping wetland will be covered with pickleweed, which will turn bright red each fall.

And Alviso, she said, will have more time together as a community — protected from rising water through the end of the century, and hopefully well into the next.

::

Richard Santos was skeptical when the wetland restoration effort first came to town. Born in Alviso in 1944, he grew up working in the canneries and saw firsthand how the community got ignored. But now, everyone seems to want a piece of Alviso.

First, it was business parks on the outskirts of town. Then proposals for a manufacturing and trucking distribution center. Housing pressures have also swooped in on this last bit of bay that had gone unnoticed for decades.

So with the wetlands, Santos thought it was just more people coming in with their own ideas for Alviso. But he soon realized saving the marsh was also going to save the community he’s fought his whole life to protect.

He remembers picking bell peppers as a kid where San Jose’s sewage treatment facilities loom today. Back then, it was just the fog, not the stench from the compost dump, that hung over town. His father worked six, often seven, days a week, but always made time to fish with him along the estuary.

“The way I was raised, everybody worked,” he said. “Everybody worked in orchards and fields and nobody was exempt. And it was — well, you didn’t know it was difficult at the time because we were so isolated.”

When a flood in 1983 submerged Alviso, Santos, a firefighter at the time, waded in chest-deep water to help his community evacuate. He still thinks about all the families that had to camp for weeks in school gymnasiums.

Now 78, Santos is still fighting for the community. Days after retiring from the fire station, he joined the agency in charge of flood protection for San Jose. He couldn’t stop working, he said, because he was worried Alviso would be forgotten.

“I still get bitter sometimes,” he said. “When you’re not treated right, you never forget it.”

Like the marshy fringes of the bay that were once erased, the people of this long-neglected town, he said, deserve a second chance.

::

One morning in April, months after Buxton had finally passed the baton, Santos threw on a tie and welcomed a crowd of high-ranking officials to Alviso. Shovels rose out of a massive pile of dirt. A ribbon awaited cutting. The clouds hung heavy with signs of rain, but no one paid much mind. It was time, at long last, to celebrate this new truce with nature.

“Climate change is real, and that means that there has to be changes. We can’t do things the same way we’ve done for years and years,” said Col. Antoinette Gant, commander of the Army Corps’ South Pacific Division. “This partnership that we have here is an outstanding model of what can be done when you bring everybody together to the table.”

In a quiet moment after the crowd dispersed, Evyan Sloane, a sea level rise adaptation specialist who had stepped into Buxton’s shoes, ruminated on the immensity of the work ahead. Seeing the project site for the first time filled her with awe. She could hardly wrap her mind around just how much restorable marshland was left in such an urbanized part of California.

“Just the sheer scale of what we’re doing here is really cool, because a lot of the projects in climate change adaptation are still trying to demonstrate that we can use nature, and this is way beyond that,” she said.

As the sky opened up and poured rain onto the land, she breathed in the damp air with joy.

“I have been looking at the maps, trying to study them — but then you get out here, and it’s so much bigger than you can even imagine.”