Compromise on plastics ban comes under fire in California Legislature. Ballot fight likely

It appears increasingly likely Californians will get a chance to vote on a single-use plastics ban in November after efforts to craft compromise legislation came under fire this week from groups supporting the ballot measure.

Led by state Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica), lawmakers submitted a bill Thursday they hoped would preempt the initiative and head off a costly initiative battle and possibly years of litigation. Some environmental groups support the legislation, but key backers of the ballot measure say it gives away too much to the plastics industry, which has fought off numerous previous attempts to restrict single-use containers, including those made of polystyrene.

Polystyrene — the lightweight foamy plastic found in disposable coffee cups and some food containers — is a dividing line in the debate. Allen’s bill does not ban polystyrene, as the ballot measure would. Instead, it calls for a 20% polystyrene recycling rate by 2025.

According to the EPA, just 3.6% of polystyrene in packaging is recycled.

“We need to get the most problematic material out of the system,” said Linda Escalante, Southern California legislative director for the Natural Resources Defense Council. She is one of the three ballot initiative petitioners, along with Michael Sangiacomo, former president of the Bay Area waste management firm Recology, and Caryl Hart, vice chair of the California Coastal Commission.

“I can’t see sacrificing the initiative over this,” she said. “We don’t want to get tied down to a flawed system for years and years.”

The initiative — known as the California Recycling and Plastic Pollution Reduction Act — would require all single-use plastic packaging and food ware used in California to be recyclable, reusable, refillable or compostable by 2030, and single-use plastic production to be reduced by 25% by 2030.

Along with banning polystyrene, it also requires the producers and distributors of plastic products to pay for the program — levying a less than 1-cent fee per item.

Critics of the initiative say its language is vague and, because it doesn’t have buy-in from the plastics industry, is potentially problematic.

They believe the legislative process and the resulting legislation will ultimately be a more effective way to regulate plastic waste, allowing for clearer regulatory directives for state agencies and plastic producers to follow.

“This bill would put California in the front of the world at fighting plastic pollution,” Allen said. “It holds producers responsible for the end use of their products.”

Among other items, the 73-page bill requires producers to reduce single-use plastic packaging and food ware by 25% by 2032 and mandates that producers pay $500 million a year in mitigation funds. It is the product of weeks of negotiations involving Allen, the plastic industry’s lobbyists, environmental groups and others.

Dart Containers, a Michigan-based plastics company and the world’s largest manufacturer of foam cups and containers, has not taken a position on the amended legislation. But Margo Burrage, Dart’s director of communications, said the company prefers the legislative route, “where a solution can be effective and comprehensive while taking into account ways to update the state’s aging infrastructure to meet the recycling and composting demands of any mandates or requirements.”

Some leading environmental groups — including the Nature Conservancy, the Ocean Conservancy, Azul and Oceana — have announced support for the latest revision of the bill. In a statement, the Nature Conservancy’s Jay Ziegler said his group welcomes the legislation and sees it “as consistent with the single-use plastic ballot measure to address the mounting plastic pollution crisis around us.”

But other environmental groups say the legislation, as drafted, doesn’t go far enough and allows the plastics industry to self-regulate.

“It’s giving them the keys to the car,” said Judith Enck, a former regional administrator for the EPA and president of Beyond Plastics, a Vermont-based environmental organization. “Would you let the tobacco industry oversee antismoking initiatives?”

In the ballot initiative’s 12-page version, CalRecycle is given wide authority over the implementation of the program.

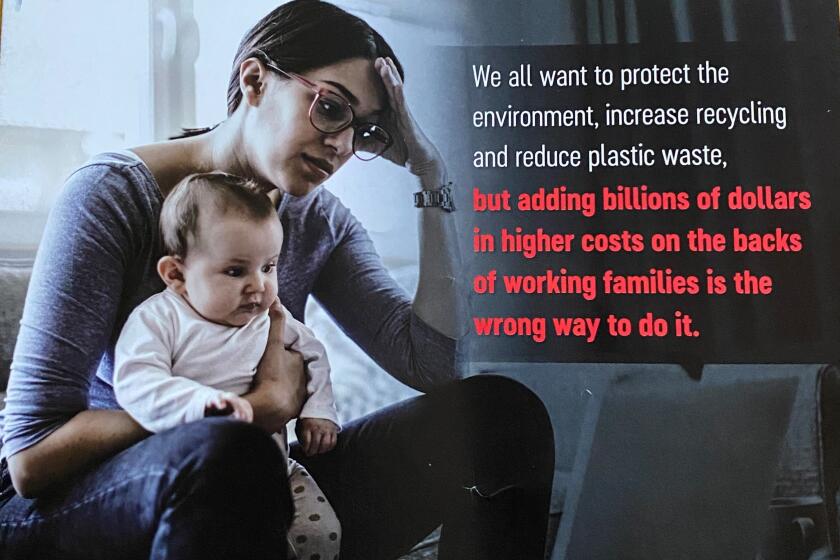

Last month, an industry-backed group, the Environmental Solutions Coalition, started targeting key lawmakers by sending mailers to their constituents. The mailers, first reported by The Times, warned that tough restrictions on single-use plastics containers would drive up costs, an effort that critics derided as deceptive and misleading.

Members of 18 environmental justice organizations, including Mothers of East Los Angeles, objected. In a June 15 letter to the ballot petitioners, the groups urged them to keep the initiative and laid out their concerns.

“Suffice it to say that we just don’t have confidence that an industry so prone to deceiving the public for so long about the impacts of its products on our communities and our planet will now take the starring role in its own demise voluntarily,” they wrote.

An industry front group, the ‘Environmental Solutions Coalition,’ is sending fliers claiming plastics restrictions will drive up costs.

In addition, environmentalists and the petitioners are concerned that the legislation doesn’t address the toxicity of plastic waste. They argue it also opens up the potential for “chemical” or “advanced” recycling in the state, which they contend does not actually recycle plastic but instead creates fuels while emitting hazardous waste products into the air.

According to a report from the U.S. General Accounting Office, chemical recycling uses heat and/or chemical reactions to break down used plastics into new plastic, fuel or other chemicals.

“In our opinion, an effective ... law defines recycling in a way that is limited to mechanical recycling, prioritizing product-to-product or closed-loop recycling as these systems reduce reliance on virgin materials,” Enck and colleagues from 20 other environmental groups, including Californians Against Waste and the Environmental Working Group, wrote in a June 15 letter to Allen.

There are no chemical recycling plants in California. Many environmentalists, however, worry that if the plastics industry is left in charge of the state’s recycling program, that would change.

“California is the fifth-largest economy in the world,” Enck said. “It’s cliche, I know, but what California does, so does the rest of the country. That’s why it’s so critical they do this right.”

More to Read

Updates

9:27 a.m. June 17, 2022: This article has been updated to reflect the position of Dart Containers on the most recent revision to the legislation.