GREENVILLE, Calif. — To descend the grade of State Highway 89 into the rubble of Greenville is to retrace the steps of a community’s trauma.

It was here that the second largest wildfire in California history — and the first ever to burn from one side of the Sierra Nevada to the other — decimated the town of about 1,000 people.

Hillsides once thick with trees are now blackened and splattered with bright blue-green hydromulch to fight erosion. The town center is a grid of bare lots and debris piles.

But while most people would see devastation here, Sue Weber sees hope and opportunity. A former nun in Mother Teresa’s order, Weber is part of an unprecedented effort to not only rebuild Greenville, but to build it back better than it was before.

It’s an endeavor that involves the Dixie Fire Collaborative, a grass-roots rebuilding coalition Weber co-chairs. It has grown to include members of an Indigenous tribe and loggers backed by an environmental nonprofit who want to convert dead and scorched trees into lumber for new homes and businesses. Above all, they say, they want to ensure a tragedy on this scale will never happen here again.

“There’s the mysteries and the beauties of destruction and creation,” Weber said. “Everything can be destroyed but now we have this capacity to create something so valuable.”

During a recent tour of Greenville’s downtown, Weber pointed to the charred remains that once held pieces of her community: That pile of rubble was the pharmacy. Over there, the post office. This was the old bed and breakfast that Weber once called home.

One thing she is adamant about is that Greenville can’t simply rebuild exactly the way it was. Even before the fire, its population was on the decline, and its poverty rate was more than double that of California as a whole. “You have to have economic development in the game,” she said.

The Dixie Fire Collaborative, which draws about 150 people to its monthly meetings at Greenville Elementary School, has drawn inspiration from other communities that have suffered disaster. Weber and others visited Greensburg, Kan., which was nearly destroyed by a tornado in 2007. Leveled buildings have been replaced with energy-efficient structures that are powered by wind. They’re also looking to Joplin, Mo., which is increasing its population a little over a decade after it too was devastated by a tornado.

“They said the biggest piece is pretty much what we recognize. Most people want to go fast,” Weber said, snapping her fingers. “Just to rebuild back as opposed to really stopping and really intentionally looking at what’s the best way to build back that’s healthy and helpful for everybody.”

For that reason, the Dixie Fire Collaborative has embarked on a multi-stage process to gather community input and create an architectural plan for the downtown.

The collaborative is working to attract broadband service to lure young professionals and remote workers. It is coordinating a popup that will see food trucks and a mobile saloon set up shop downtown, a first step toward drawing people back to the area to spend money at local establishments. And it’s exploring cost-effective, fire-hardened housing alternatives like those made of insulated concrete or cross-laminated timber, or built with 3-D printers or assembly line production.

For the Mountain Maidu people, it was exceptionally painful to watch the fire take out the heart of their ancestral territory.

If they’d still been stewards of the land, they say, the fire would never have burned as severely as it did.

For centuries, the Maidu cultural hub of Kótasi, meaning “on the snowline,” thrived in the area that is now Greenville, said Trina Cunningham, executive director of the Maidu Summit Consortium, a nonprofit dedicated to reacquiring and protecting ancestral lands.

The Maidu regularly burned vegetation in the surrounding hills for scores of purposes: to stimulate the production of seeds, to control pest populations and to keep the land open so they could better spot intruders and game. The fires also helped the Maidu obtain basket making materials, tools and medicine.

“They knew when to burn and where to burn and how to burn,” said Allen Lowry, vice chair of the Maidu Summit Consortium.

The land became adapted to these regular, low-intensity fires set under ideal conditions, but in the mid-1800s, that balance was upended.

“During the Gold Rush, everything changed very quickly,” Cunningham said. “It was a horrible history of our families in this place.”

Settlers slaughtered the Maidu, exposed them to diseases, took their land and forced their children into boarding schools that stripped them of their culture. They logged the hills surrounding the village, removing the largest, most fire-resilient trees, and they clear-cut swaths of forest, replacing the diverse flora with tightly-packed, single-species plantations that “burn like gas,” Lowry said. They also suppressed both cultural burns and nature-sparked fires.

During the Dixie fire, winds funneled flames down the hills toward Greenville. The combination of dry brush and dense timber whipped the conflagration into a high-severity crown fire, in which flames run across the treetops, gaining speed and spitting out embers.

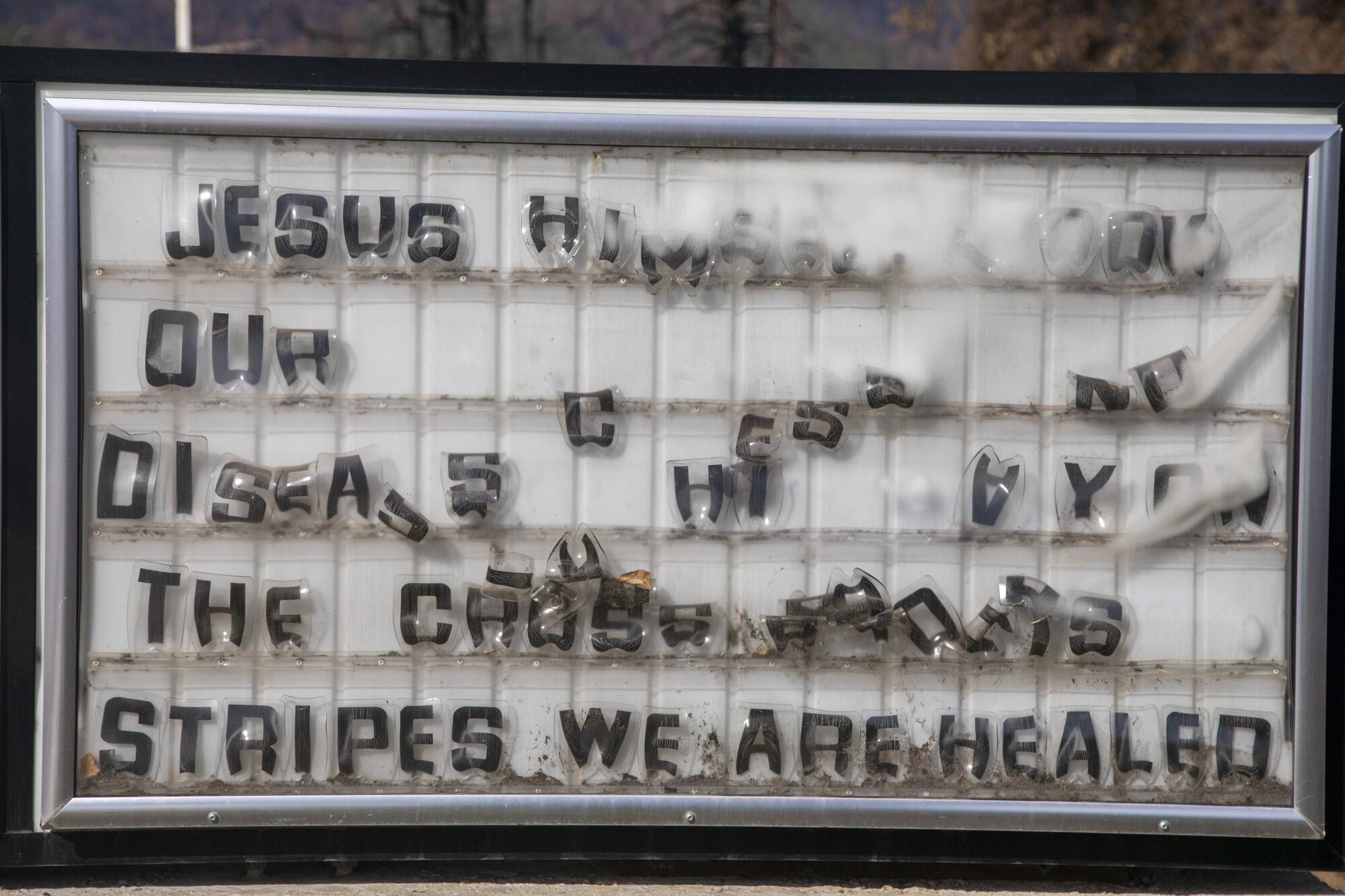

Firefighters trying to defend Greenville were overwhelmed by myriad spot fires. The flames burned so hot, many of the street lamps melted. The Greenville Rancheria’s offices and health facilities were destroyed.

“We would never have let it get to this state,” Cunningham said. “And to have to watch it when we knew that it could have been prevented is just horrific. It’s like another form of torture.”

The Maidu had just two years before claimed a significant victory when Pacific Gas & Electric Company returned 2,325 acres of ancestral meadow land called Tásmam Kojóm. They had been working to reintroduce cultural burning to reduce the effects of future catastrophic blazes when the Dixie fire ripped through, upending their plans and leaving them grappling with what to do next.

In a development Lowry called “almost ironic,” state investigators have since found that PG&E’s equipment sparked the Dixie fire, and the utility has said it may also have been responsible for starting another fire that merged with the Dixie.

Lowry estimates that in the past two decades, about 90% of the Maidu’s ancestral land has burned in repeated fires. “We read that the climate is changing, and we can see it, we can feel it,” he said. “And fires like this are just going to be the way it’s going to be.”

Today, as Greenville rebuilds, Cunningham sees an opportunity for the Maidu to cast aside the feeling that they are refugees in their own homeland. It’s possible now for the town to embrace the Maidu’s culture, creating what she calls an immersion experience. The larger community has been receptive, she said.

Possibilities include a park with interpretative panels in Maidu, street signs in Maidu or buildings decorated with cultural designs, Cunningham said. She would also like to see a Maidu Institute of Ecology built in Plumas County, with different learning campuses where Maidu people can pass on knowledge about their concepts of existence and relationship with nature.

“We are in those discussions of rebuilding,” Cunningham said, “to make sure that the Mountain Maidu aren’t erased again from one of the communities that are so important to us.”

Nearly a year after fire swept over Greenville, the only activity on the streets of downtown are workers hauling concrete and cutting down the tens of thousands of burned trees that must be removed from roadsides to mitigate hazards or cleared from lots so people can rebuild.

Randy Pew, a third-generation logger born in Greenville who now lives in nearby Crescent Mills, describes the trees as “incredibly valuable, but not worth a dime.”

They are valuable because they can be milled into timber and used to provide residents with lower-cost building material, he said. But they’re also worthless because there is nowhere to take them to be milled. Existing mills are backlogged processing trees salvaged from their own burned landholdings.

Pew, who runs J&C Enterprises with his son Jared, hopes to change that. He has partnered with the nonprofit Sierra Institute for Community and Environment to build a sawmill in Crescent Mills, using a grant from the Sierra Nevada Conservancy. They cut their first board in December and hosted a ribbon-cutting ceremony May 18.

“We’re going to call it Dixie pine,” Pew said as he showed off the mill’s uniquely designed equipment, including greenhouses engineered to be used as solar dry kilns and gearhead motors he found on Craigslist and sent two men to Canada to purchase at an enormous cost saving.

It’s the kind of creative partnership that representatives of the state and nonprofit say is sorely needed to both invigorate local economies and support sustained, landscape-scale forest restoration activities. It’s also ripe for replication across the Sierra Nevada, which has many shuttered sawmills and an abundance of burned trees, they said.

Jonathan Kusel, founder and executive director of the Sierra Institute, recalls driving past burned stumps and wondering what had happened to the rest of the tree. In many cases, he learned, agencies like the California Department of Transportation were paying contractors large sums to grind the trees up into wood chips by the side of the road.

“How can we do something to add value, or utilize the value that’s in that log?” Kusel wondered. “So that was the birth of the idea.”

A rural sociologist, Kusel has devoted his life’s work to restoring and preserving both ecosystems and economies, which he sees as inseparably linked. It’s not lost on him that a partnership with a for-profit logging firm might raise eyebrows. But to him, people are a part of these landscapes, the same as trees, birds and bears. He believes it’s possible to meet their needs for both wood products and jobs in a sustainable way.

“We have lumped all loggers and mill operators into this bad category,” Kusel said. “But you hear Randy talking and you do hear that concern for the system. And what it also entails is a concern for the social system.”

Right now, J&C is sourcing logs from lots that homeowners’ insurance companies have paid them to clear, as well as from CalTrans. Before the agency agreed to provide the logs, Pew estimates that 15 houses’ worth of wood was being chipped each day.

“It’s really heartbreaking to drive by these massive trees and watch them busting them up with an excavator and ram them through a chipper,” said lumber mill employee Dan Kearns, a volunteer firefighter whose Facebook broadcasts made him a local folk hero during the Dixie fire.

But Kearns said the heartbreak turns to fury “when you get told it’s going to be $400 a square foot to rebuild your house.”

The operators hope to eventually transition from processing salvage logs to milling trees removed from forests during thinning projects intended to restore the landscape to more fire-resilient precolonial conditions. They say it’s a strategic way to supplement grant and government funding to help ensure the work continues and that the local community benefits.

“When people are thinning the forest, it’s so hard for the material to pay its way out of the woods,” said Georgia Reid, a wood utilization project specialist with the Sierra Institute. “A lot of times the treatment can’t even happen because there’s no disposal pathway.”

At a mid-March meeting of the Dixie Fire Collaborative, emceed by Weber and attended by Randy Pew, whose other son Tyler is helping lead the committee’s rebuild team, community members continued to feel their way back from the brink.

Over bratwursts provided by Mary’s German Grill, people shared news of progress on a new gas station and a popular jerky manufacturer that had laid a foundation in its reconstruction effort. There were updates on debris removal and soil sampling and questions about solar panels and fire sprinkler permits.

Then Reid announced the mill would soon formally open. The sedate crowd erupted in claps and whistles.

“It’s really helping rebuild hope,” Kusel said later. “We can recover.”