California promised to close its last nuclear plant. Now Newsom is reconsidering

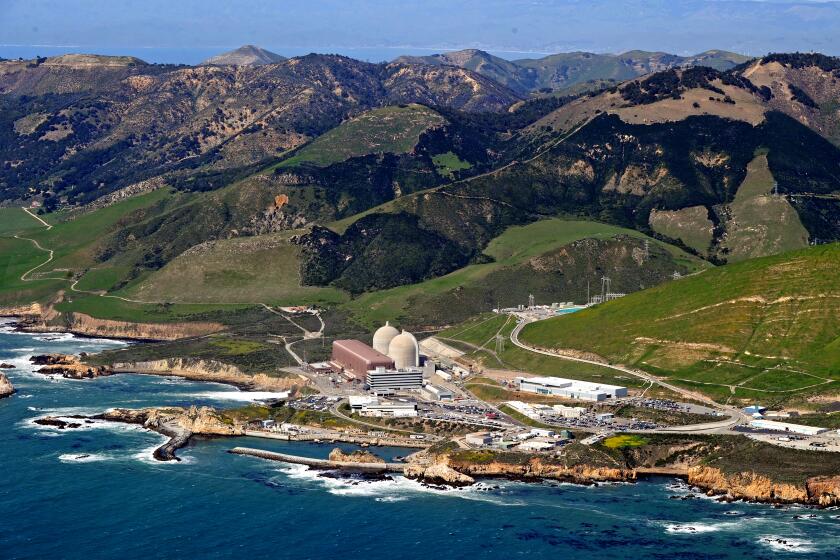

With the threat of power shortages looming and the climate crisis worsening, Gov. Gavin Newsom may attempt to delay the long-planned closure of California’s largest electricity source: the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant.

Newsom told the L.A. Times editorial board Thursday that the state would seek out a share of $6 billion in federal funds meant to rescue nuclear reactors facing closure, money the Biden administration announced this month. Diablo Canyon owner Pacific Gas & Electric is preparing to shutter the plant — which generated 6% of the state’s power last year — by 2025.

“The requirement is by May 19 to submit an application, or you miss the opportunity to draw down any federal funds if you want to extend the life of that plant,” Newsom said. “We would be remiss not to put that on the table as an option.”

He said state officials could decide later whether to pursue that option. And a spokesperson for the governor clarified that Newsom still wants to see the facility shut down long term. It’s been six years since PG&E agreed to close the plant near San Luis Obispo, rather than invest in expensive environmental and earthquake-safety upgrades.

But Newsom’s willingness to consider a short-term reprieve reflects a shift in the politics of nuclear power after decades of public opposition fueled by high-profile disasters such as Chernobyl and Three Mile Island, as well as the Cold War.

Nuclear plants are America’s largest source of climate-friendly power, generating 19% of the country’s electricity last year. That’s almost as much as solar panels, wind turbines, hydropower dams and all other zero-carbon energy sources combined.

Diablo Canyon is the state’s largest clean energy source. Will emissions rise after it closes?

A recent UC Berkeley poll co-sponsored by The Times found that 44% of California voters support building more nuclear reactors in in the Golden State, with 37% opposed and 19% undecided — a significant change from the 1980s and 1990s.

The poll also found that 39% of voters oppose shutting down Diablo Canyon, with 33% supporting closure and 28% unsure.

Nuclear supporters say closing plants such as Diablo would make it far more difficult to achieve President Biden’s goal of 100% clean energy by 2035, and to mostly eliminate planet-warming emissions by midcentury — which is necessary to avert the worst impacts of climate change, including more dangerous heat waves, wildfires and floods, according to scientists.

Nuclear plants can produce power around the clock. The stunning growth of lithium-ion battery storage has made it easier and cheaper for solar panels and wind turbines to do the same, but those renewables still play much less of a role when the sun isn’t shining and wind isn’t blowing, at least for now.

The U.S. Commerce Department, meanwhile, is considering tariffs on imported solar panels, which could hinder construction of clean energy projects that California is counting on to avoid blackouts the next few summers, as Diablo and several gas-fired power plants shut down. Newsom said in a letter to Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo this week that her department’s tariff inquiry has delayed at least 4,350 megawatts of solar-plus-storage projects — about twice the capacity of Diablo Canyon.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

He urged Raimondo to “take immediate action to resolve this issue as soon as possible.”

“This Department of Commerce tariff issue is one of the biggest stories in the country,” Newsom told The Times’ editorial board. “Looking at retroactive 250% tariffs for everything coming out of Malaysia or Vietnam, and Taiwan, elsewhere — this is serious.”

The governor said he’s been thinking about keeping Diablo open longer since August 2020, when California’s main electric grid operator was forced to implement rolling blackouts during an intense heat wave. Temperatures stayed high after sundown, leaving the state without enough electricity to keep air conditioners humming after solar farms stopped producing.

A few hundred thousand homes and businesses lost power over two evenings, none of them for longer than 2½ hours at a time, officials said. The state only narrowly avoided more power shortfalls during another heat storm a few weeks later, highlighting the fragility of an electric grid undergoing a rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Newsom spokesperson Anthony York said the governor’s decision to reconsider Diablo Canyon’s closure timeline was driven by projections of possible power shortages in the next few years. Those projections, he said, came from the California Independent System Operator, which oversees the electric grid for most of the state.

Anne Gonzales, a spokesperson for the grid operator, couldn’t immediately provide the projections. She said in an email that the agency supports “considering and exploring all options” for keeping the lights on, as doing so gets harder due to climate impacts including more extreme heat waves, more aggressive wildfires and hydropower supplies diminished by drought.

Newsom told the editorial board that reliable electricity is “profoundly important.” He also acknowledged the growing number of scientists, activists and former U.S. energy secretaries who have pressed him to rescue Diablo for climate reasons.

“Some would say it’s the righteous and right climate decision,” Newsom said.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory is the subject of a new documentary, “In the Dark of the Valley.”

Extending the plant’s closure deadline — PG&E is on track to shutter the first reactor in 2024, and the second in 2025 — wouldn’t be easy even with funding from the Biden administration. The federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission would need to hurry to renew Diablo’s operating license. Newsom suggested several state agencies would need to be involved, too — as well as the Legislature, which last year declined to even give a committee vote to a bill designed to keep Diablo Canyon open.

For Newsom to extend Diablo’s life, he would also need PG&E’s cooperation in applying for federal funds. The company committed to closing the plant in 2016, when it struck a deal with environmental groups and its own union workforce to get out of the nuclear business — a decision that was eventually endorsed by regulators and lawmakers.

Asked whether PG&E is open to changing course on Diablo, spokesperson Lynsey Paulo said in an email that the company is “always open to considering all options to ensure continued safe, reliable, and clean energy delivery to our customers.”

“PG&E is committed to California’s clean energy future, and as a regulated utility, we are required to follow the energy policies of the state,” Paulo said.

Newsom said he’s asked PG&E to consider what it would take to keep Diablo Canyon open longer, including the possible role of federal funds.

“Based on the conversations we’ve been having with PG&E, it’s not their happy place,” he said.

The company declined to comment on how federal funds might be used to Diablo’s benefit. State officials have previously told The Times that operating Diablo past 2025 would require billions of dollars of upgrades to comply with earthquake safety rules, and with environmental regulations governing the use of ocean water for power-plant cooling.

To Ralph Cavanagh — co-director of the clean energy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, and a key architect of the 2016 deal to shut down Diablo Canyon — applying for federal funds would be a fool’s errand.

Cavanagh said it’s his understanding that only certain types of power companies with specific economic challenges are eligible for the nuclear funding, and PG&E isn’t one of them. The infrastructure bill approved by Congress last year — which set aside the money Newsom is interested in seeking — says funds are only available to nuclear plants that compete in a “competitive electricity market,” which Diablo Canyon does not.

York, Newsom’s spokesperson, acknowledged in a text message that there’s “some question about whether Diablo is eligible” for the federal money, and that “PG&E would need to talk to” the federal Energy Department to get more clarity.

Cavanagh also said solar, storage and other clean energy resources could replace Diablo cheaply and reliably, as envisioned in the 2016 deal. As for the supply chain and tariff issues that have slowed solar and battery storage projects, he pointed out that both of Diablo’s reactors will still be online through summer 2024, with the second sticking around until August 2025.

“We have time to get our arms around that,” he said.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

While NRDC supports keeping some nuclear plants operating where safety risks are lower, the technology’s fiercest critics argue nuclear is fundamentally unsafe. They consider Diablo Canyon especially risky because it’s near several seismic fault lines along California’s Central Coast. As far back as the 1970s — when then-Gov. Jerry Brown protested the plant’s construction — Diablo has stirred fears of an earthquake-driven meltdown spreading deadly radiation across the state.

Nuclear waste is another concern. In the absence of a permanent underground storage repository for spent fuel, radioactive waste is piling up at power plants across the country, including the shuttered San Onofre facility along the coast in San Diego County.

Rescuing Diablo Canyon is far from California’s only option for averting blackouts.

There are many other steps the state might take — and in many cases is actively taking — to keep the lights on after sundown the next few summers, such as adding batteries to the grid, paying homes to use less energy and coordinating electricity supplies more closely with other Western states. Longer-term options include investing in geothermal energy and offshore wind.

Newsom told The Times’ editorial board he plans to announce a “resilience fund” in next month’s update to his annual budget proposal, to pay for projects that would help avoid rolling blackouts the next few years.

But the governor also thinks keeping Diablo Canyon around at least a little while longer is worth considering, despite the political backlash it might provoke. He pointed to modeling by the state’s Public Utilities Commission and Independent System Operator showing that worsening heat waves — fueled by climate change — are making it harder to keeps the light on.

“We threw out the old playbook. We’re going to worst-case scenario,” he said. “We are being very sober.”

Supporting nuclear is a key climate priority for the Biden administration. But federal officials hadn’t seemed optimistic PG&E would apply for a share of the Energy Department’s $6-billion nuclear bailout fund. During a visit to Southern California last week, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm told reporters she’s “not sure that the community [around] Diablo Canyon is on board yet.”