Lee Vining, Calif. — In a fevered bid for wealth, white ranchers and gold miners began pouring into the remote Mono Lake Basin east of Yosemite in the 1850s, taking over the ancestral lands of Native Americans who had existed there from time immemorial.

To members of the Mono Lake Kutzadika Paiute tribe, it was an assault on their traditions, their culture and their very survival.

They had thrived for thousands of years amid the bounty and hardship of the Sierra Nevada range, surrounded by its wildlife, its water resources and its sacred places, such as a spring that women used for purification rituals and that was festooned with rock carvings.

Now, 150 years after the Mono Lake Paiute culture was vanquished, the tribe has dwindled from 4,000 members to just 83. Tribal leaders are also facing the long and expensive process of gaining federal recognition of their Native American status — a step needed to establish a land base, a measure of sovereignty, and to qualify for assistance to help with healthcare, education and protection of sacred sites.

“Stress is an understatement,” said Charlotte Lange, 67, chairwoman of the tribe that despite being unrecognized maintains a tribal organization and holds monthly meetings in Lee Vining, a small town known as an eastern gateway to Yosemite along U.S. 395 near Mono Lake. “We just want a place to call home, and time is running out.”

“It breaks my heart to hear tribal elders worry that they won’t live long enough to see it happen,” she said. “Eight of our elders passed away in the last year and a half alone.”

Lange wishes federal officials were more appreciative of the long and difficult history they are trying to overcome.

California’s Native American population plunged from 150,000 to 30,000 in the mid-1800s, according to Benjamin Madley, a UCLA historian and author of “American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873.”

The Native California population has rebounded to about 150,000, many of whom belong to the state’s 110 federally recognized tribes. Those groups are able to determine their own destiny, and in many cases, that destiny has involved lucrative gambling palaces.

The Mono Lake Paiutes are among roughly two dozen unrecognized and landless tribes in California that have initiated petitions for federal recognition by the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Few of those efforts are likely to succeed, experts say, because they usually cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, require extensive documentation and research by anthropologists, historians and tribal members, and can take a decade or more.

“Luckily, the Mono Lake tribe is well documented and has a strong case,” said Dorothy Alther, an attorney with California Indian Legal Services who is representing the tribe on a pro bono basis.

“But these things take years,” she added. “It’s a matter of keeping up with federal rules and regulations that never stop changing, and tribal attorneys that come and go.”

The Mono Lake Paiute had something to crow about in September when Rep. Paul Cook (R-Yucca Valley) introduced a bill that would bypass the petition process by having Congress extend federal recognition to the tribe. It raised expectations, only to expire as the session ran out.

Cook went on to become a San Bernardino County supervisor, and it remains unclear whether his successor, Rep. Jay Obernolte (R-Big Bear Lake), plans to resubmit the bill.

“If Obernolte doesn’t resubmit the bill, we’ll find someone else to do it,” Alther said. “In any case, we’d like the bill to be as bipartisan as possible.”

Lange holds out hope, in part, because of President Biden’s nomination of Deb Haaland, a congresswoman from New Mexico, to lead the Interior Department. If approved, Haaland would make history as the first Native American to oversee an agency that manages millions of acres of public land and the powerful Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Critics among Indigenous groups, however, point out that every new administration vows to do better on Native American lands, but rarely lives up to the promises.

***

Without federally protected land to call home, Mono Lake Paiute tribal members are scattered across the state. But their spiritual hubs remain nearby the almost million-year-old alkaline Mono Lake in the shadows of the jagged eastern escarpment of the Sierra Nevada.

The tribe takes its name from its traditional word for what was once a high-protein food source, the pupae of tiny black alkaline flies that carpet the Mono Lake shoreline. They have a crunchy, nutty flavor, which makes them very snackable when dried.

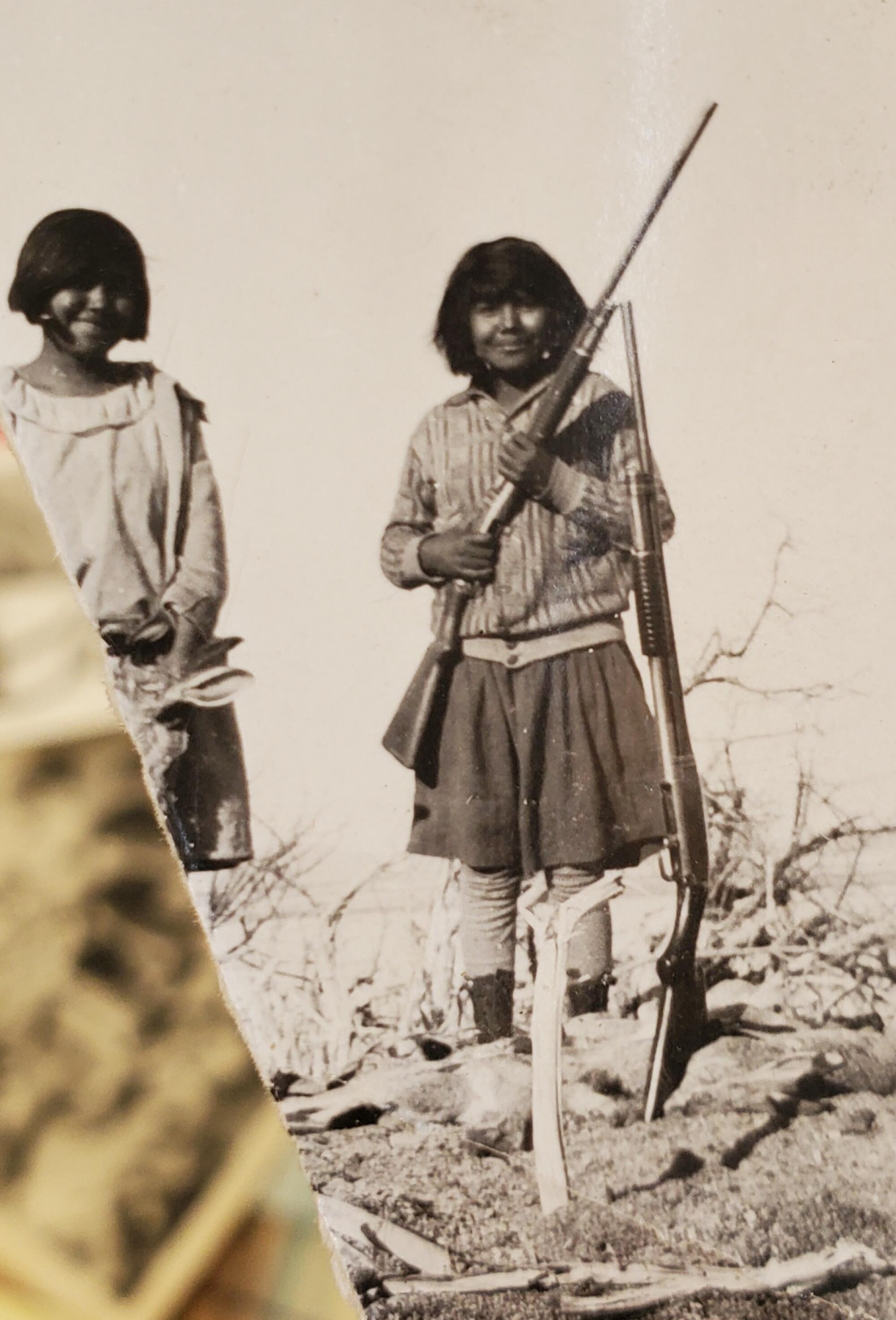

The tribe’s ancestors adapted to life in the high-altitude valley with short growing seasons by irrigating villages, harvesting pine nuts and hunting pronghorn antelope and jackrabbits for food and pelts for clothing.

During long treks over a network of routes in the Sierra Nevada, they protected their skin from mosquito bites and sunburn by coating themselves with a layer of mud.

Reminders of their presence — grinding stones, arrowheads and stone carvings known as petroglyphs — are found throughout the region, and are considered to be sacred by Native Americans.

***

The plight of the Mono Lake Paiute is an all too common story for California’s tribal communities, Madley said.

“Despite the signing of 18 treaties in the 1850s,” he said, “the U.S. Senate refused to ratify any of them.”

“That’s because state officials and news organizations directed their congressional delegation in Washington to vote against the treaties,” he said. “Their argument being that the land was too valuable because it might contain gold, timberlands, water and ranchlands.”

“After gold was discovered just north of Mono Lake in 1859,” he said, “ranchers unleashed hundreds of cattle in the area for sale to miners seeking to strike it rich.”

After that, he said, “there was a slew of massacres along the eastern Sierra Nevada.” They included the slaughter of a large group of men, women and children on the northern shores of Mono Lake.

In 1904, Congress broke up tribal lands throughout the region into allotments. These tracts were given to individual members of “homeless tribes” to produce income from sales and leases.

The new allottees, however, had few defenses against whites who had mastered the art of making a quick profit. Among them were agents sent from Los Angeles in the 1920s to secure a reliable water supply for the burgeoning metropolis about 350 miles to the south.

Within a few years, most of the Kutzadika allottees, had sold their lands to white outsiders, who were often seeking water rights.

In 1950, the tribe requested an investigation into their living conditions in hopes that federal officials might “set aside land for us,” according to Bureau of Indian Affairs records. Instead, they were told that there were no public lands available, and all the water resources were owned by Los Angeles.

In 1976, the tribe launched its ongoing effort to petition for federal recognition by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The tribe touts support from more than a dozen other recognized tribes throughout the Sierra Nevada, as well as the Mono Lake Committee, a 41-year-old nonprofit conservation organization.

Support also comes from the Forest Service, which has set aside a grove of Jeffrey pine trees for traditional purposes, and the National Park Service, which permits tribal members to enter Yosemite National Park at no cost.

The stakes are high. A federally recognized tribe has sovereignty and does not pay taxes. It is also exempt from following state or county legal ordinances. Yet it is entitled to full service from local law enforcement authorities and fire departments, hospitals, and road and flood control systems.

It is eligible for assistance from legal programs created to help impoverished tribes reclaim lands lost over the decades through tax sales, fraud and violence, and to find new housing for members displaced by disasters such as the wildfire that a year ago destroyed dozens of buildings and killed at least one person in the community of Walker, Calif., about 44 miles north of Mono Lake.

***

There has always been a hope among tribe members for a Mono Lake Reservation — a place to preserve the group’s dialect, stories and values for future generations. To some, that dream seems to be as distant as ever.

Gazing out at Mono Lake as the sun set over the snow-clad Sierra Nevada peaks on a recent weekday, Ronda Kauk, 37, a Kutzadika mother of four and lifelong resident of Lee Vining, placed a hand over her heart, trying not to cry.

“It’s hard and it’s sad,” she said, “and it hurts me right here.”