First-of-its-kind clean hydrogen plant planned for Los Angeles County

An energy company with big ambitions to produce the clean fuel of the future announced a deal Tuesday with Lancaster officials to make hydrogen by using plasma heating technology — originally developed for NASA — to disintegrate the city’s paper recyclables at temperatures as high as 7,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Solena Group’s process has no commercial track record, and the company has not yet secured financing to build its $55-million facility in Lancaster, in northern Los Angeles County. Solena is one of many firms looking for ways to cheaply produce hydrogen without generating planet-warming gases in hopes that the clean-burning fuel will one day replace oil and gas for transportation or heating.

But the company’s process, which uses so-called plasma torches, caught the attention of Lancaster Mayor R. Rex Parris.

The city will expedite Solena’s permitting process and send the company its paper recyclables, rather than paying to dump them in a landfill. Some U.S. cities have been sending recyclables to landfills since China stopped accepting exported waste in 2018.

If the hydrogen plant doesn’t materialize or otherwise fails, Parris said in an interview, there’s little downside for the city.

The upside would be pioneering a technology that could dramatically cut emissions. Lancaster will own a small stake in the plant.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“If we continue producing energy as we have been, we’re not going to be here in 50 years,” Parris said, referring to the impacts of climate change. “I’m excited to see how well it works, and how quickly we can expand this through the nation.”

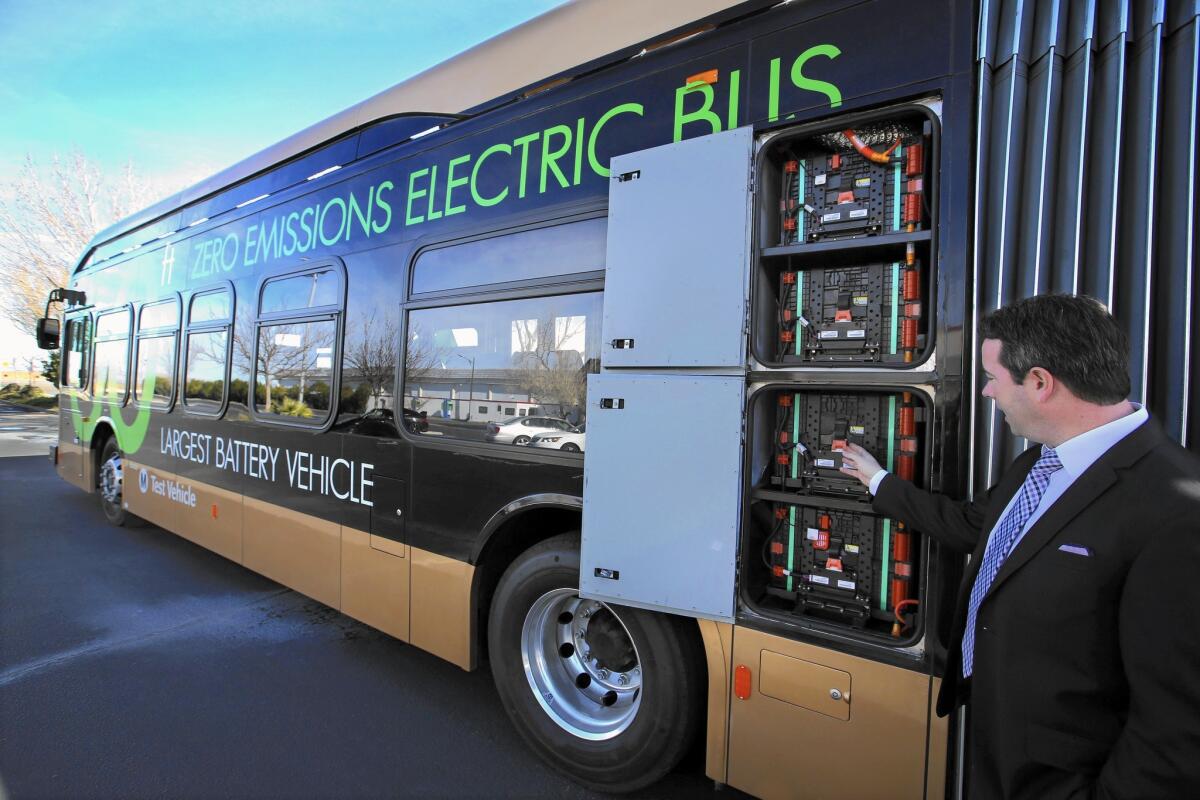

A maverick Republican, Parris has made climate change his signature issue. He helped make Lancaster the first city in Southern California to ditch its privately owned electric utility and buy cleaner power for residents. He also convinced the Chinese automaker BYD to build an electric bus factory in Lancaster.

As a trial lawyer, he is representing thousands of people suing Southern California Gas Co. over the alleged health impacts of the 2015 methane blowout at the company’s Aliso Canyon storage facility.

“Most of what we do is the first time it’s ever been done,” Parris said.

Solena Group’s chief executive, Robert Do, has been honing his waste-to-fuel technology for decades.

Do co-founded the company in the 1980s with Salvador Camacho, a former NASA engineer who helped the space agency develop a plasma heating technique that could generate temperatures high enough to simulate re-entry to Earth’s atmosphere. The technology was critical to testing the heat shields that would protect the first Americans in space as they returned to Earth.

A 1994 NASA publication described plasma heating as “passing a strong electric current through a rarefied gas to create a plasma — ionized gas — that produces an intensely hot flame.” Camacho started a spinoff company utilizing the technology in 1971.

“It’s a pretty well-demonstrated industrial equipment,” Do said in an interview.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Solena Group would use some of the gas it produces — mostly hydrogen and carbon monoxide — to power its plasma torches.

The company has tried and failed to build a commercial facility before. In 2015, for instance, a joint venture between Solena and British Airways to produce jet fuel at a facility in London fell apart after oil prices crashed, undercutting the project’s economics.

Do is hopeful that California policies requiring cleaner energy will create an atmosphere where his technology can thrive.

“Our technology can only follow what the market demands are,” he said.

Welcome to the first edition of Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change, energy and the environment in the American West.

There’s huge demand for hydrogen in industrial processes such as petroleum refining and fertilizer production.

The fuel burns cleanly, but it’s typically produced from coal or natural gas, in processes that emit planet-warming carbon dioxide. A tiny portion of global supply is produced through electrolysis, which involves splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen atoms.

As solar and wind power have gotten cheaper, experts have grown more optimistic about the potential to produce hydrogen through electrolysis powered by renewable energy. In theory, that could make hydrogen an abundant, climate-friendly fuel.

In addition to cleaning up industry and transportation, “green hydrogen” could replace some of the fossil natural gas that homes and businesses use for heating and cooking, a possibility touted by Southern California Gas Co. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, meanwhile, said last year that it would attempt to build the world’s first power plant fueled by hydrogen.

Green hydrogen is still too expensive to make much of a dent in global demand. But costs are moving in the right direction.

The consulting firm BloombergNEF released a report in March finding that with supportive public policies, renewable hydrogen could meet 24% of the world’s energy demands by 2050, and reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels and industry by one-third.

The analysis didn’t consider the type of process that Solena Group is proposing, known as “plasma gasification.”

While the concept isn’t totally unheard of, it has yet to be proven commercially, several hydrogen experts told The Times.

Scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a federal research institute, studied gasification as part of a recent report. They found that producing hydrogen through gasification of organic waste — basically applying heat and pressure until the waste becomes a gas — could be one of the cheaper strategies for bringing down carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere.

How would that work? The trick is to understand that organic waste — such as paper goods — might otherwise decompose in landfills, where it would ooze methane, a heat-trapping gas. Diverting that waste from the landfill, and converting it to hydrogen, would avoid some of those emissions. And the hydrogen would also displace a dirtier fuel, such as diesel in a heavy-duty truck.

“There’s a price of hydrogen at which it starts to become economical,” said Sarah Baker, a chemist at Lawrence Livermore and the report’s lead author.

Can methane gas bubbling up from manure ponds help California fight climate change?

Baker and her colleagues considered only conventional heating methods, not higher temperature plasma torches.

But Solena Group is targeting the same goal: Cheap hydrogen with minimal carbon emissions and an overall planetary benefit.

The company hopes to sell hydrogen to operators of fueling stations for hydrogen-powered vehicles, a small but growing market.

“For something like passenger vehicles, we already have an increasingly low-cost, low-carbon alternative in electric vehicles,” said Ben Gallagher, an expert in emerging technology at the consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. “For heavy-duty vehicles like trucking or street sweepers or garbage trucks or buses, this is a potential avenue for hydrogen, because a battery would be so heavy.”

Solena Group has a lot still to prove. The company has partnered with Fluor Corp., a multinational engineering and construction firm, to build its plant in Lancaster, which it hopes will be permitted by early next year and producing hydrogen by late 2022.

If the firm can produce hydrogen at the low price point it’s claiming — reliably enough to attract investors, and without generating noxious byproducts — it would be a big deal, said Jeffrey Reed, a renewable fuels expert at the University of California, Irvine.

“Gasification is potentially quite cost effective for producing hydrogen,” he said.