California could face power shortages if these gas plants shut down, officials say

It’s been nearly a decade since California ordered coastal power plants to stop using seawater for cooling, a process that kills fish and other marine life.

But now state officials may extend the life of several facilities that still suck billions of gallons from the ocean each day.

Staff at the California Public Utilities Commission recommended this month that four natural gas plants in Southern California, which are now required to shut down in 2020, be allowed to keep operating up to three additional years. Without the gas plants, PUC staff said, the state may face power shortfalls as soon as summer 2021 — specifically on hot days when energy demand remains high after the sun goes down and solar farms stop generating electricity.

Energy regulators aren’t panicked, since there’s still time to make up for the expected shortfall.

And critics say shortages are unlikely and regulators are being overly conservative.

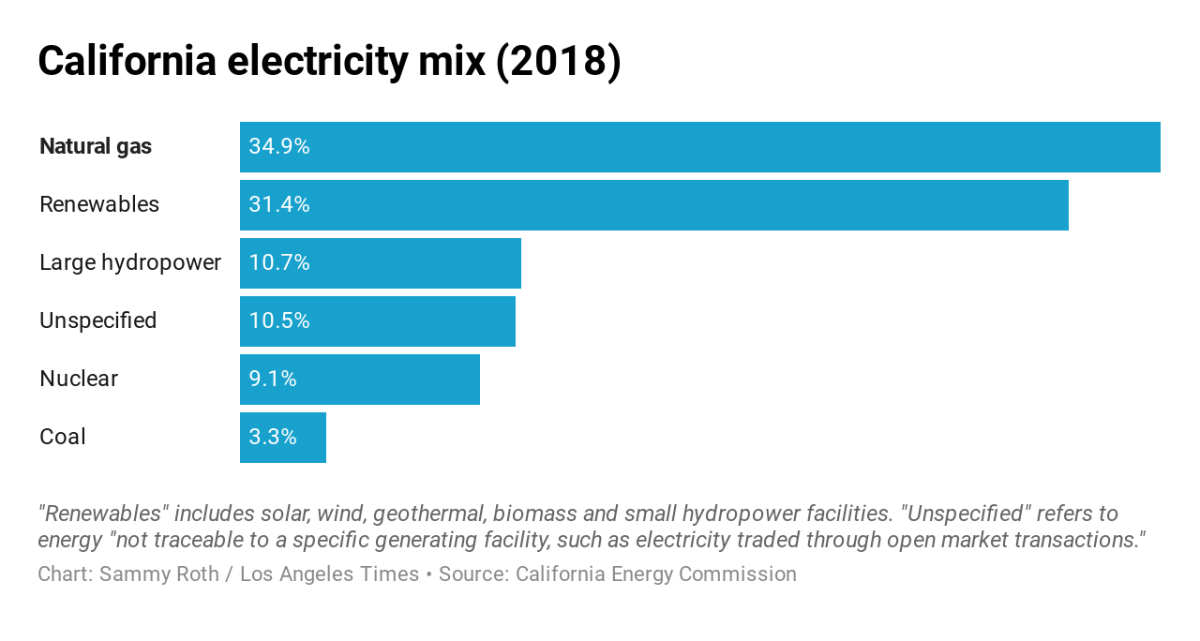

Still, the PUC’s proposal highlights increasingly urgent questions about how much natural gas California should continue to allow on its electric grid, and for how long. The state now gets one-third of its electricity from renewable sources, and state law requires 100% climate-friendly energy by 2045.

Burning natural gas contributes to the climate crisis. But it’s also California’s largest power source.

Taking too much gas off the grid too fast could inadvertently derail California’s clean energy and climate goals, said Jan Smutny-Jones, chief executive of the Independent Energy Producers Assn., a trade group that represents developers of gas plants and renewable energy facilities.

“If we suddenly start having reliability problems, that’s a good way for losing popular support for the greening up of our energy system,” he said.

PUC staff are recommending the commission ask another agency, the State Water Resources Control Board, to allow gas-burning generators to operate past 2020 at four coastal power plants: Alamitos, Huntington Beach, Redondo Beach and Ormond Beach. PUC staff also say Southern California Edison and other energy providers should sign contracts for 2,500 megawatts of new power, to replace those coastal gas plants when they do eventually shut down.

The five-member Public Utilities Commission won’t vote on the staff proposal until Oct. 24 at the earliest. A spokesman for the state water board said in an email that it would be “premature for us to comment,” since the board hasn’t yet received a formal request to extend the life of the coastal gas plants.

Loretta Lynch, a former president of the Public Utilities Commission, thinks the whole exercise would be a waste of ratepayer money.

Lynch said extending the coastal gas plants and requiring energy providers to buy thousands of megawatts of new power — purchases that could include additional natural gas — would be “diametrically opposed to state goals.” The PUC has presented “zero evidence” of a need for new power, she said.

Lynch pointed out that the analyses projecting shortfalls don’t actually show California won’t have enough power come 2021. Rather, they show utilities might not be able to meet a requirement to have a reserve of 15% more power than they expect to need — a requirement Lynch believes is excessive.

“Everybody knows we’re got plenty of power,” she said.

The bucolic orchards of Sutter County north of Sacramento had never seen anything like it: a visiting governor and a media swarm — all to christen the first major natural gas power plant in California in more than a decade.

San Diego Gas & Electric, California’s third-largest investor-owned utility, also says the 15% reserve margin provides enough of a cushion that immediate action isn’t needed. In written comments to the PUC, SDG&E described another assumption underlying the projected shortfall — that California can’t count on out-of-state power being available during high-demand periods — as “unreasonably conservative and unsupported by recent history.”

Advocates for California’s marine ecosystems aren’t happy, either.

Shelley Luce, president of the environmental nonprofit Heal the Bay, said she wants to see the four coastal gas plants shut down and replaced with renewable energy. That’s what the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power is planning to do with its own ocean-cooled gas units, following Mayor Eric Garcetti’s decision earlier this year not to spend billions of dollars rebuilding three facilities with dry-cooling technology that doesn’t use ocean water.

If the state water board does extend the life of the four coastal power plants, officials should require a “substantial increase” in protection and restoration of habitat for the fish, shellfish and microscopic organisms that would be harmed, Luce said.

“Every minute those plants operate, marine life is being impacted,” she said.

State officials insist the projected power shortfall is real, and serious. So does Southern California Edison.

There are several factors at play, according to the PUC and the California Independent System Operator, which runs the power grid for most of the state.

One is the planned retirement of thousands of megawatts of capacity at a time when California increasingly needs energy generators that can fire up in the evening, to replace the solar farms that supply more and more of the state’s power during the day.

Another is California’s reliance on out-of-state power plants to supply a portion of its energy. That arrangement is growing tenuous as other states shut down coal plants and pass their own clean energy targets, leading to a tightening of supply across the western United States, officials say.

A third factor is California’s use of large amounts of hydroelectric power, which depends on water supplies that are getting more uncertain as climate change leads to longer, more extreme droughts.

The state’s energy market has probably had excess capacity in recent years, said Mark Rothleder, vice president for market quality and regulatory affairs at the Independent System Operator. But that’s starting to change, as on-again, off-again solar and wind farms replace coal, gas and nuclear power.

If state officials don’t act soon, there could be rolling blackouts or sharp increases in electricity prices come 2021, Rothleder said. The 15% cushion is crucial, he said, because it ensures the state can withstand power plant outages or higher-than-expected demand.

“We need new capacity,” Rothleder said.

The Eland solar contract had been delayed due to concerns raised by the city electrical workers union.

It’s not clear what kinds of additional power Southern California Edison would buy if the PUC signs off on its staff’s recommendations.

Lithium-ion batteries that can store solar energy for use after dark are one option, said Colin Cushnie, Edison’s vice president of power supply. The utility could also invest in energy efficiency, or “demand response” programs where customers are paid to use less power during high-demand periods.

Natural gas is another option.

Cushnie said his utility has no plans to contract for new gas plants. So did Ted Bardacke, executive director of the Clean Power Alliance, a government-run energy provider that serves about 3 million people across Southern California and would also be required to buy new power under the PUC proposal.

But those energy providers could sign contracts with existing gas plants that have extra capacity, or were mothballed by their operators because cheap solar and wind power undercut their economics. Those contracts could extend the lifetimes of gas plants that would otherwise close, or remain closed.

Calpine Corp., a Houston-based company that owns 20 gas plants in California, has “brought back units that we expected to retire,” Matt Barmack, the company’s director of market and regulatory analysis, told state officials last week during a discussion of the expected power shortfalls.

Calpine and other gas plant owners see a long-term future for their investments, even as California works to achieve net-zero planet-warming emissions by 2045. Calpine commissioned a study, released in June, finding California will still need at least 17,000 megawatts of gas capacity in the middle of the century as a backstop for solar and wind. In theory, those plants would fire up rarely, with utility ratepayers paying their owners to keep them ready to go.

But many clean energy advocates argue California should get off gas entirely — partly because of the carbon emissions generated by burning gas, and partly because gas plants also emit local air pollution, often in disadvantaged communities that have long suffered from hazardous air quality.

Two of the coastal gas plants that could soon get a new lease on life — Ormond Beach Generating Station in Oxnard and Alamitos Generating Station in Long Beach — are located in or near neighborhoods with high pollution levels.

Ventura County’s largest city is a coastal town where miles of power plants, vast tracts of farmland and private oil and gas holdings limit access to the shore.

In the long run, some experts say, new types of energy storage and other clean technologies could reduce or eliminate the need for gas — protecting the climate and fish along the coast.

David Olsen, who chairs the Independent System Operator’s board of governors, thinks the projected power shortages highlight the need for California to invest in geothermal power plants, which are more expensive to build than wind and solar farms but can generate climate-friendly electricity around the clock. One of the country’s most powerful geothermal reservoirs sits beneath the ground at the southern end of the Salton Sea, in Imperial County.

With more geothermal, “we wouldn’t have to be finding these very large amounts of resources to make up for the solar when the sun sets,” Olsen said.