He ran the NAACP. Now he’s leading the Sierra Club’s fight against climate change

This story originally published in Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Leading one of America’s largest and most influential environmental advocacy groups has never been an easy task.

But after the tumult that has rocked the Sierra Club the last few years, it may be especially challenging.

The Oakland-based nonprofit has grappled with the legacy of its founder, John Muir, with some Sierra Club members and staff describing Muir as blatantly racist and others rejecting that narrative as wildly overstated. The club was roiled by allegations of workplace discrimination and harassment, and by frustration among volunteers who said its national leadership was determined to strip the autonomy of their local chapters. Amid those debates, longtime executive director Michael Brune resigned in 2021.

Now Ben Jealous has stepped into the fray — and he’s got an ambitious agenda for tackling the climate crisis.

Jealous started last month as the Sierra Club’s seventh executive director. He’s the first person of color to lead the 131-year-old organization. He’s got a unique background, having previously run the NAACP, the nation’s largest civil rights group.

In an interview this week, Jealous told me he’s eager to keep making the Sierra Club more diverse and to focus its energies on social injustices — injustices that are worsened by climate change and, at times, make it harder to fight climate change. In his first blog post on the club’s website, for instance, he decried a planned freeway expansion through Black and Latino neighborhoods in Milwaukee, saying it would fuel greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, and continue a history of racist urban planning.

Part of his plan for the Sierra Club is beefing up staffing in places facing the greatest environmental injustices.

“We’re only as strong as our weakest link,” Jealous said. “The states that we historically have had the least staff are the states where corporations are prepared to do the most mischief. There’s an urgent need for us to change that.”

Jealous has a long history of environmental activism, informed by his childhood growing up on California’s Monterey Peninsula and making regular trips to redwood groves and Yosemite National Park. As a teenager, he led tours at Monterey Bay Aquarium and helped organize a rally at the state capitol to protest clear cutting of timber. As a reporter and editor at the Jackson Advocate, a Black-owned newspaper in Mississippi, he wrote about cancer clusters and industrial pollution.

At the NAACP, he launched a climate justice program and helped persuade the leaders of the Sierra Club and Greenpeace — another influential environmental nonprofit — to support civil rights activists in their campaign to defend voting rights.

“There is no green vote without the Black or brown vote,” Jealous told me, quoting fellow activist Van Jones.

So what are Jealous’ top policy priorities? How does he plan to help California and other states move beyond natural gas, without breaking the bank for families who can’t afford induction stoves? And where does he think big solar farms should be built?

The following highlights from our conversation have been edited and condensed for clarity.

**

You’ve been on a listening tour over the last month, visiting Sierra Club chapters across the country. What have you heard from staff and volunteers about John Muir’s legacy and about the need to build a more inclusive movement?

Muir was a white man in the 19th century who said a lot of things that sounded like a white man in the 19th century. He was also somebody who was clearly wrestling with the issues of the day. When he was on his 1,000-mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico, they say he carried Thoreau’s papers — his arguments against slavery — in his pocket.

The Sierra Club has had a real reckoning. Those sorts of reckonings are healthy. They’re never easy. And they’re a necessary part of being an organization that’s accountable and prepared to evolve and become ever more inclusive, in a country that’s becoming ever more diverse.

The listening tour is still going. Some of these chapters have received a lot of attention from national leaders of the Sierra Club. Some of them much less so. The Mississippi director has led that state for 24 years, and he says I’m the first executive director to ever visit his state. And before the end of my first month, I’ll be the first executive director to come there twice.

What have you heard from local chapters about the tension between grass-roots volunteers and national staff, in terms of who sets the organization’s agenda?

The power of the Sierra Club has always been its members. When I was growing up in Monterey, it was the club’s Ventana chapter that supported me and my buddies when we started the first high school chapter of the Student Environmental Action Coalition. While it’s always the hardest number to quantify, your greatest asset in a membership organization is the volunteer hours.

To the extent the Sierra Club has had tensions internally, we should welcome that as a sign of our vitality. I benefited early in my career from being trained by proteges of Martin Luther King. Many of them would repeat the lessons that Dr. King taught them about organizing. One of those lessons, “If you are comfortable in your coalition, then your coalition is too small.”

In this democracy, to get big things done, we need big, uncomfortably large coalitions. The Sierra Club is the only such coalition among the national environmental organizations. You see it reflected in our national staff, in multiple chapters. There is clearly a lot more work to be done. But we are on a path to become big enough to win the even bigger victories that we must win.

One of the Sierra Club’s most successful campaigns has been Beyond Coal, which has contributed to the shuttering of hundreds of coal plants across the United States. How do you plan to tackle natural gas, another fossil fuel that is now America’s largest source of electricity, and which is burned for heating and cooking in tens of millions of homes?

First off, we’re still in the midst of Beyond Coal. We’re still fighting to stop people from bringing coal-fired plants back online — to power cryptocurrency server farms, for instance.

However, we also have the capacity to push further. Beyond oil and gas is the obvious next frontier, and more broadly beyond petrochemicals. We’re also focused on accelerating our ambition to electrify everything, everywhere, for everybody.

How do you make sure that “electrify everything” doesn’t become a financial burden for families that can least afford it? We’re talking about people needing to replace their gas heaters and stoves — and gasoline-powered cars — with electric appliances and vehicles that are, at least for now, usually more expensive.

The good thing is that there’s a Moore’s Law that seems to be happening across our electrification goals. You see battery power getting bigger, and costs getting lower. You see solar panel efficiency increasing rapidly. You see LED grow lights becoming more and more effective, and cheaper. So it’s reasonable to expect that the things that are problems today — like supply-chain issues that drive up the cost of electric vehicles — will not be problems tomorrow.

When it comes to saving the planet, the social injustice that’s the greatest obstacle is poverty. I’m based in Maryland. Poverty is why my neighbors in West Virginia historically would vote to support politicians who they knew would blow up the mountains they loved and dump them into the streams they loved — because they needed those coal-extraction jobs.

Racism has always been the wedge that kings and oligarchs have used to weaken people’s ability to assert their claims to justice. It’s an artifact of an old colonial divide-and-conquer strategy. So for those at the Sierra Club who have wondered why we are so on fire to fight racism, I explain that it’s an obstacle to us saving the planet. Racism helps to ensure poverty, which keeps people desperate in making bad decisions about the future of the planet.

I’m guessing you liked the financial incentives for rooftop solar panels, electric heat pumps and other clean energy technologies in the Inflation Reduction Act, which President Biden signed last year.

My optimism about this moment for the planet, and for the Sierra Club, comes from fact we have carrots on the table. It gives us something to help guide industry and impoverished communities in the right direction.

I’m also hopeful when I see the Sierra Club’s Massachusetts chapter working to introduce a bill in the state Legislature that would cut red tape and increase incentives for accelerating solar panel deployment across commercial rooftops and as parking garage canopies. That’s the type of thing I believe bipartisan cooperation is possible on, and urgently needed.

I’ve been writing about the challenge of building large solar and wind farms, when there’s so often opposition from environmentalists — sometimes including local Sierra Club chapters — who say these renewable energy projects can destroy wildlife habitat. There are also significant environmental conflicts around mining for lithium and other metals needed for electric cars. How do you plan to walk that tightrope between clean energy and conservation?

We need to relieve as much pressure on wild places as possible. That’s why it’s urgent to accelerate solar adoption across commercial rooftops and on lands that have already been disturbed by industry. Right now in many instances, the pressure to put it on the plains — or cut down a forest, even — comes from the difficulty of doing it in other places. We need to figure out how to align incentives and cut red tape, and get solar panels onto all the surfaces it would enhance, not destroy.

The extraction issues are going to be even thornier. I’ve spoken to investors who estimate we are 50 million tons of copper short of what our electrification goals will require. All of that cannot come from the Global South, let alone from countries that may be ruled by dictatorships, or by governments that otherwise have zero environmental regulations.

Sierra Club members are understandably accustomed to stopping everything they can when it comes to extraction. And yet we have to reckon with the fact that there’s a need to extract, in order to revamp how we power the globe.

Figuring out how to do that responsibly starts with getting our activists in conversation with environmentalists in the Global South, and helping each side absorb that this needs to be done in an equitable way. The United States must increasingly take responsibility for meeting its own needs, and not require people who are politically disempowered to take all the poisons.

Last question: Are there any California-specific environmental issues that you’re especially eager to work on?

The future of Pacific Gas & Electric. As a thought experiment, I was ruminating on the importance of the battle to save Hetch Hetchy — the way it shaped the Sierra Club, the way that it shaped environmentalism in California, the way it made drinking water always seem more sacred in San Francisco. I asked myself, what would be the equivalent of that battle today?

The mayor of San Jose has suggested that the state should take over PG&E and move to rapidly transition the company to a customer-owned cooperative. That’s an idea that I want to dig into, that we will dig into. In the context of all the wildfires, all the power outages, all the complaints — it’s certainly a reasonable question for the mayor of San Jose to ask, and one that we as a club need to really engage and figure out what we think is possible.

That idea also feels relevant to your earlier point about prioritizing rooftop solar. PG&E and California’s other investor-owned utility companies have been pushing for years to reduce financial incentives for rooftop solar — and now they’re finally getting what they want. PG&E’s critics say rooftop solar is a threat to the utility business model.

The shameless profit-maximizing of power companies is an obstacle to saving our planet. One way or the other, we need to get them working for all of our long-term future, not just the short-term gain of their shareholders.

ONE MORE THING

Jimmy Carter, America’s 39th president, entered hospice care over the weekend. The 98-year-old “decided to spend his remaining time at home with his family and receive hospice care instead of additional medical intervention,” the Carter Center said.

If you’re not familiar with Carter’s environmental legacy, this piece by the Washington Post’s Maxine Joselow is worth reading. During his four years in office, Carter protected more than 100 million acres in Alaska, championed solar power as a means to burn less oil and created the federal Energy Department, which today plays a crucial role in funding climate solutions.

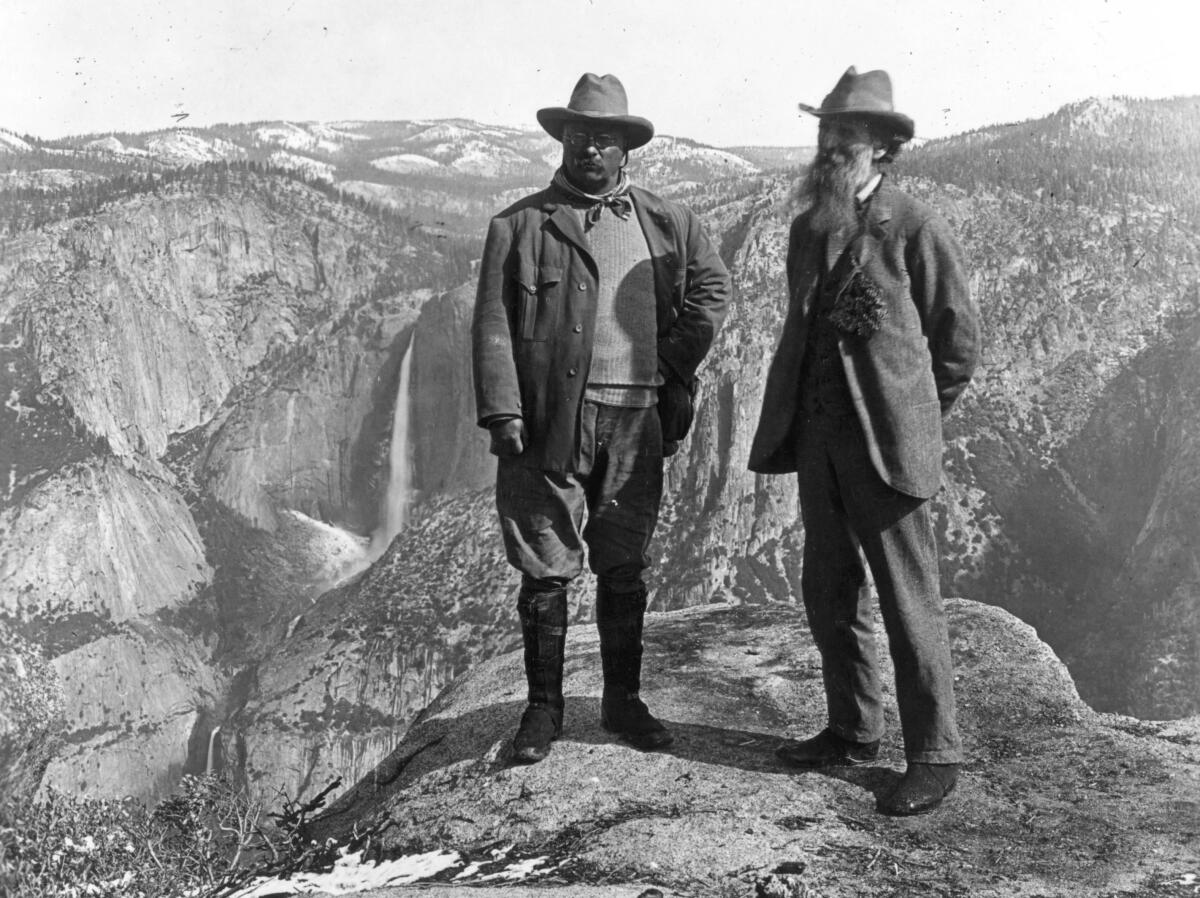

On a related note, I’m currently reading “The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America,” by the historian Douglas Brinkley. The book opens with an anecdote about President Roosevelt bursting into a White House Cabinet meeting in 1903 to breathlessly declare that he had seen an unusual bird for Washington, D.C., in the winter.

Not a bad quality in a president, if you ask me.

That’s all for today. We’ll be back in your inbox on Tuesday. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous editions, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. For more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.