These five people could make or break the Colorado River

This is the June 16, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Alex Cardenas. J.B. Hamby. Jim Hanks. Javier Gonzalez. Norma Sierra Galindo.

There’s a good chance you’ve never heard of them. But with the Colorado River in crisis, they’re arguably five of the most powerful people in the American West.

They’re the elected directors of the Imperial Irrigation District, or IID, which provides water to the desert farm fields of California’s Imperial Valley, in the state’s southeastern corner. They control 3.1 million acre-feet of Colorado River water — roughly one-fifth of all the Colorado River water rights in the United States.

And if you live in Southern California — or in Phoenix, Las Vegas, Denver or Salt Lake City — the future reliability of your water supply will depend at least in part on what IID does next.

That’s because the Colorado River has been over-tapped for a century — and now climate change is making things worse, sharply reducing the river’s flow. Lake Mead is just 28% full, its lowest level ever. Lake Powell is at 27%. A federal official said this week that the seven states dependent on the river — including California — will need to cut their water use between 2 million and 4 million acre-feet next year to avoid outright catastrophe at the two major reservoirs.

That’s a startling amount of water — at the high end, about eight times what Los Angeles consumes from all sources in a year.

“The challenges we are seeing today are unlike anything we have seen in our history,” Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton said during a Senate hearing Tuesday, as reported by my colleague Ian James.

Those kinds of cutbacks almost certainly won’t be possible without IID’s help. And that help is not guaranteed.

The Imperial Valley’s landowning farmers have fought bitterly to protect their senior water rights — hence the importance of the five individuals whose campaigns they fund, and whose actions they closely scrutinize. In 2002, for instance, the IID board voted down a proposal to sell lots of Colorado River water to San Diego County. Under pressure from the George. W Bush administration, they eventually reversed themselves — a move that invited the wrath of farmers, with long-lasting political consequences.

As recently as last year, IID didn’t participate in a deal between California, Arizona and Nevada agencies to leave more water in Lake Mead. Two years earlier, the district sued to block a similar agreement known as the Drought Contingency Plan.

Now the Imperial Valley will once again be asked to help solve the West’s water woes. Will those five board members be willing to strike a deal to use less water? Or will they bow to pressure from the valley’s farm barons to resist?

I posed that question to J.B. Hamby — IID’s youngest board member but already a mighty force in the region’s politics.

Hamby was elected in 2020 at age 24, after an aggressive campaign in which he slammed the incumbent director for supporting the San Diego water deal two decades earlier. He argued that future water transfers should be subject to a public vote.

But when we spoke this week, Hamby sounded ready to negotiate. He suggested IID might need to implement a “temporary, emergency fallowing program,” in which farmers are paid not to plant crops in certain areas — a concept many locals have historically seen as a threat to the Imperial Valley’s economy and way of life, but one of the most reliable ways to save large amounts of water. IID could also increase the incentives it pays farmers to install more efficient irrigation equipment.

Why bother with any of that when the Imperial Valley’s senior water rights — some of the oldest on the Colorado River — should protect the region from mandatory cutbacks, at least until almost everyone else runs out of water? That’s an easy one, Hamby said: If Lake Mead gets so low that water can no longer pass through Hoover Dam, the Imperial Valley is toast.

“Our sole water supply is the Colorado River. We don’t have groundwater, we don’t have other streams or other rivers that we can depend on like other agencies,” he said. “If we lose the Colorado River, we don’t have anything.”

Of course, IID’s not about to forgo a bunch of water for nothing.

First and foremost on Hamby’s mind? Additional support for the Salton Sea. The sparkling desert oasis has been shrinking as less irrigation runoff flows from Imperial Valley farms fields, resulting in large amounts of air pollution in the low-income, largely Latino region, and an ecological crisis for fish and migratory birds. California has dedicated hundreds of millions of dollars to restoring wildlife habitat and tamping down toxic dust from the lake’s drying shores, but those efforts are years behind schedule.

If IID agrees to use less Colorado River water the next few years, that will mean even less water flowing into the Salton Sea. Any deal to boost Lake Mead needs to accelerate restoration efforts at the Salton Sea, Hamby said — while also indemnifying the irrigation district against legal responsibility for any public health or environmental damage from reduced inflows.

It was lack of support for the Salton Sea that prompted IID to sue over the Drought Contingency Plan three years ago.

“We have this horrible situation where you can’t save both Lake Mead and the Salton Sea at the same time,” Hamby said.

The Imperial Valley will also be looking for funding to counteract the economic harm from reduced crop production. The money could come from the infrastructure bill signed by President Biden last year. It would support not only farmers who fallow their fields, Hamby said, but also “the tractor people and the seed people and the bee people and everybody else who help form this economic ecosystem” — as well as non-farming groups and businesses that will feel the ripple effects.

Hamby stressed that all these ideas are preliminary. And he made clear that he’s not talking about another permanent water transfer like the one with San Diego County, but rather Imperial leaving unused water in storage in Lake Mead.

So maybe IID plays a key role in addressing the immediate crisis on the Colorado River. Longer term, though, water managers in the West’s ever-growing megacities continue to eye the Imperial Valley as an ideal place to permanently reduce water use — in part by irrigating more efficiently, and in part by retiring farmland dedicated to super thirsty crops such as alfalfa.

That will be a tougher nut to crack, politically speaking.

After accounting for water it’s sending to San Diego and other parts of Southern California, IID has used about 2.5 million or 2.6 million acre-feet of Colorado River water annually the last few years. But when I asked Hamby what a more sustainable number would be — in other words, how much less water Imperial should use — he didn’t want to go there.

Plenty of local farmers still use flood irrigation, and Hamby acknowledged there’s room for more efficiency. But the region has “a long-term interest in continuing to have a vibrant farming economy,” he said — and “people still eat irrespective of whether it’s wet or dry.” The Imperial Valley is one of the most fertile places in the country. It’s a major producer of lettuce, carrots, beets, broccoli, onions, grapefruit, dates, cantaloupes and other crops — not to mention cattle for beef and dairy.

Hamby also pointed to the huge amounts of water that are still wasted, in his view, in cities such as Los Angeles.

“It’s very easy to point at the alfalfa field,” he said. “But what about drying out the lawns and useless grass?”

The question of Imperial’s long-term water use could be settled between now and 2026, when current rules for sharing water shortages across the Colorado River Basin expire. The federal Bureau of Reclamation and the seven states along the river — California, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming — are gearing up to negotiate new rules.

Which brings us back to the five individuals who could make or break those all-important talks — and the Imperial Valley farm barons who play an outsize role in determining who those individuals are.

Hamby is up for reelection in 2024, so there’s no guarantee he’ll still be around. But he won his first election by a big margin, and he served as IID vice president his first year in office, even as he clashed with his colleagues. He told the Imperial Valley Press that fellow IID directors Alex Cardenas and Norma Sierra Galindo called him “little Satan” and accused him of having no soul, to which the newspaper reports that he responded by telling them “to do something that is biologically improbable to themselves.”

Galindo might not be on the board much longer. Four years ago, she survived a challenge from a candidate backed by a handful of farmers seeking greater control of the region’s Colorado River supplies. Now she’s down by 231 votes as officials finish counting ballots from last week’s election. Her opponent, Imperial City Councilmember Karin Eugenio, was endorsed by the Imperial County Farm Bureau and received campaign support from some of the same growers who failed to oust Galindo in 2018.

Cardenas, whose opponent Andrew Arevalo was bankrolled by some of those same farmers, is up by 23 votes, out of more than 3,500 cast. And in IID’s third district, where Jim Hanks is retiring, the leading candidate is Gina Young Dockstader, the farm bureau’s choice and a recipient of substantial agriculture industry campaign funds. She’ll be headed to a November runoff.

As crazy as it sounds, a few thousand votes in an often-ignored corner of California could help determine the fate of a dwindling river that nearly 40 million people depend on for drinking water. And these elections are so low-turnout that double-digit margins of victory aren’t uncommon. It’s not hard for farmers to influence the outcomes with five-digit sums.

There’s no guarantee that IID directors elected with ag industry backing will do the farmers’ bidding. And not all farmers want the same thing. While many of them oppose Colorado River reductions, a few are eager to sell water to the highest bidder.

But messy as the Imperial Valley’s politics are, if you live in the American West or care about its future, they matter to you.

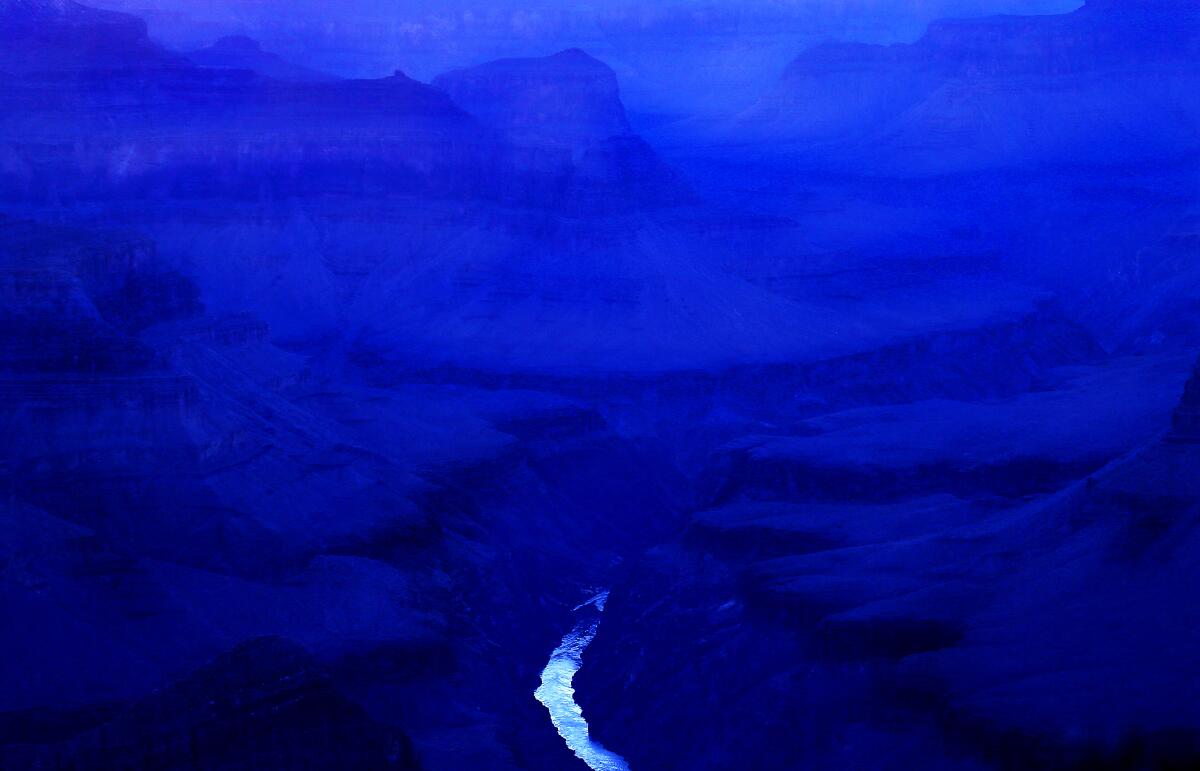

That’s true from the Rocky Mountains to the Grand Canyon, and from the lights of the Las Vegas Strip to the shores of the Gulf of California. Those places are getting hotter, drier and more fire-prone — but they’re still beautiful, each in its own way, as L.A. Times photographers Luis Sinco and Brian van der Brug document in this amazing photo journey down the Colorado River.

Take some time and soak in their images. You won’t regret it.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

DROUGHT AND FLOODS

Did Californians learn anything during the last drought? Some of our water-saving habits stuck, but we’ve still got a long ways to go to live in harmony with the drying climate, The Times’ Hayley Smith writes. If you’re looking for ways to cut back, here are tips from my colleagues Karen Garcia on how to find leaks in your home, Jeanette Marantos on how to care for drought-tolerant plants and Laura J. Nelson on how long to stay in the shower. And since many of you have asked, golf courses do face watering restrictions — but those restrictions are a lot more slippery than what’s being required of homes, Ian James and Hayley Smith report. State officials have also cut off San Joaquin River flows to thousands of cities and farms, per Ian and Sean Greene.

While much of the West grappled with drought, Yellowstone National Park shut down due to torrential floods, forcing more than 1,000 visitors to flee the park. “I’ve heard this is a 1,000-year event, whatever that means these days. They seem to be happening more and more frequently,” Yellowstone Superintendent Cam Sholly said, per this story by the AP’s Matthew Brown and Lindsay Whitehurst. Indeed, this is what climate change looks like in the West — an overall drying trend, but when the water does come, watch out. Extreme heat certainly doesn’t help. Death Valley hit 122 degrees over the weekend, a record for that date, while UC Davis had to bring its commencement ceremony to an abrupt halt due to dangerously high temperatures. Seven people were hospitalized and dozens more reported heat-related illness after attending the graduation, my colleague Gregory Yee reports.

Environmentalists slammed the Los Angeles River master plan approved by L.A. County supervisors this week. The county “made us believe that through its steering committee we would have real community engagement, and that it intended to think out of the box and not just add more concrete to the channel,” one activist told my colleague Louis Sahagún. Also along the L.A. River, the polluting Farmer John’s meatpacking plant that for years produced Dodger Dogs is shutting its doors, Thomas Curwen and Andrew J. Campa report for The Times. Like many Western rivers, the Los Angeles has been reshaped by large amounts of concrete. In fact, the San Pedro River in Arizona and Mexico is the last major free-flowing river in the desert Southwest — and conservationists say a new Endangered Species Act listing could help protect the waterway, the AP’s Felicia Fonseca reports.

FORESTS AND FIRES

Only 62% of federal firefighter positions are filled — and the pay raise promised by Congress last year is still in limbo. Those are just two details from this disturbing story by my colleague Alex Wigglesworth on the morale crisis facing firefighters as bigger, more aggressive blazes wreak havoc on their mental and physical health. And you’ve probably heard this before, but California could be facing a terrible summer (and fall) of fires. “It’s climate change,” Orange County Fire Authority Chief Brian Fennessy said, per this story by Alex and Hayley Smith. “I’m not a scientist, but I’ve been doing this 40-plus years, and I’ve never seen fire spread the way it is.” This weekend, a blaze broke out in Angeles National Forest, followed by another one Wednesday.

Pacific Gas & Electric not only ignited the Dixie fire — its “excessively delayed response” allowed the blaze to get out of control, California fire officials say. Details here from Hayley Smith, who writes that more than 10 hours elapsed between the initial spark and a PG&E worker discovering the fire. Nearly 1 million acres burned, in the second-largest fire in the state’s recorded history. Separately, PG&E pleaded not guilty in the 2020 Zogg fire, which was sparked by its equipment and killed four people. The embattled utility company also pledged to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2040, five years ahead of California’s deadline, the AP’s Kathleen Ronayne reports. But PG&E hasn’t offered many details yet to back up that climate commitment.

A subset of environmentalists opposed to forest thinning — which most experts see as an important tool for minimizing wildfire risk — continue to challenge projects they see as harmful logging in disguise. One such fight is playing out on the north side of Southern California’s Big Bear Lake, The Times’ Louis Sahagún reports, in a debate over bald eagles, e-bikes and the best way to keep communities from burning down. Another one is roiling Yosemite National Park, where opponents of ongoing forest thinning say the National Park Service should have done an environmental analysis first, Louis writes. Conservationists are also suing the Biden administration to protect old-growth forests in Oregon and Washington, the AP’s Andrew Selsky reports.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Los Angeles wants to dramatically expand public transit before the 2028 Olympics — but can the city pull it off? The Times’ Rachel Uranga took a look at L.A.’s plans and talked with Sen. Alex Padilla about the potential for federal funding. But lest anyone forget that ditching petroleum-fueled cars will be super hard, look to Ventura County, where the oil industry just spent nearly $6 million to defeat new regulations at the ballot box, as Cheri Carlson reports for the Ventura County Star. And as for Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to end the sale of new gasoline vehicles by 2035, state officials are looking for ways to make sure it doesn’t drive up costs for low-income drivers, per Nadia Lopez at CalMatters. Elsewhere in the West, some state officials say the Biden administration’s desire to build electric car chargers along remote rural highways isn’t feasible, the Wall Street Journal’s Jennifer Hiller writes.

It’s been 19 years since California passed a law to prohibit agricultural burning — and the ban still hasn’t happened, even though it was originally supposed to take effect by 2010. San Joaquin Valley residents breathe some of the nation’s deadliest air, and farmers burning abandoned crops only makes it worse, my colleague Tony Briscoe writes. Drought is part of the problem, with farmers who don’t have enough water to sustain their orchards and vineyards sometimes tearing them up and burning them.

Arizona is renting land to a Saudi company at below-market rates, so that the company can pump lots of groundwater to grow alfalfa that it sends to Saudi Arabia to feed cattle. That’s the finding of an Arizona Republic investigation by Rob O’Dell and Ian James. The aquifer the company has tapped is also designated as a potential future water source for Phoenix. In other news, researchers say the Colorado River Basin may have experienced an even worse drought 1,800 years ago than the one we’re suffering now, per Matthew Renda at Courthouse News Service... so I guess that means Arizona and the rest of us will be fine?

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Renewable energy is “bailing out” Texas as the state suffers an unusually early heat wave, driving up electricity demand as people crank up their air conditioners. So says one of the Lone Star State’s leading energy experts, who told CNN’s Ella Nilsen that a growing fleet of wind turbines and solar farms “spares us a lot of heartache and a lot of money.” In Texas and elsewhere, though, there are serious headwinds to expanding that fleet. Supply chain issues have gotten so bad that two California energy providers are suing renewable power developer EDF over its termination of solar-plus-storage contracts, per this Reuters story by Nichola Groom. And in California’s Imperial Valley, companies preparing to mine lithium for energy storage systems and electric car batteries say the state might kill the industry before it gets started with a high tax, the Desert Sun’s Janet Wilson reports.

America’s largest power company has long refused to promise “net-zero” greenhouse gas emissions by a certain date. Now NextEra Energy is instead pledging “real zero” — a plan to cut climate pollution close to nothing by 2045 without offsets or carbon capture. It’s a wildly ambitious plan, as Katherine Blunt reports for the Wall Street Journal, and it marks a fascinating evolution for a company that has built solar farms in the California desert and hopes to construct a giant hydropower project near Joshua Tree National Park. NextEra’s plan also depends heavily on green hydrogen. Speaking of which — the Biden administration finalized a $504-million loan guarantee to support a massive green hydrogen project that could help Los Angeles stop burning fossil fuels at a power plant in Utah, per Utility Dive’s Ethan Howland. For background, see my recent coverage of L.A.’s Intermountain plans.

The Biden administration is investigating 160 coal ash ponds where the toxic waste could be contaminating groundwater, including sites in Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming and Montana. Details here from Hannah Northey at E&E News. In Montana, Northern Cheyenne and Crow tribal members want state officials to require a thorough cleanup at the Colstrip coal plant that not only protects drinking water aquifers, but also creates hundreds of jobs, Kelsey Turner writes for Native News Online. Back at the federal level, environmentalists are frustrated that President Biden still hasn’t nominated anyone to lead the office that oversees coal mine cleanups, James Bruggers reports for Inside Climate News. Biden has been in office for more than 500 days.

ONE MORE THING

The Sierra Nevada tree thought to be Earth’s oldest living organism — a 4,853-year-old Great Basin bristlecone pine known as Methuselah — has competition. Researchers in Chile say an ancient cypress called Gran Abuelo may be six centuries older.

If that’s the case, much respect to Gran Abuelo — it’s not a competition. The key lesson here is about doing what it takes to keep both trees strong. As L.A. Times letters editor Paul Thornton writes, “With global warming unleashing catastrophic change on the planet’s 3 trillion trees, they’ll need our help — and our restraint — to continue outlasting human civilizations.”

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.