Newsletter: Here are the last coal plants clinging to life in the American West

This is the Feb. 10, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

As long as West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin III holds the keys to the Senate, it’s highly unlikely President Biden can win passage of legislation requiring utility companies to shut down fossil-fueled power plants and replace them with clean energy.

But that hasn’t stopped coal plants from continuing to fall like dominoes.

Yes, U.S. consumption of the dirtiest fossil fuel increased last year as rising natural gas prices made coal relatively more competitive. But the long-term trends are clear: Utility companies are moving faster and faster to phase out coal power as solar panels, wind turbines and battery storage systems get cheaper, and as many states enact laws to fight climate change.

Two years ago this month, I tallied the few dozen remaining coal plants in the American West, noting which ones were scheduled to close and which power companies planned to keep burning coal indefinitely. In December 2020, I updated the tally.

After the events of 2021, there are now fewer than 10 Western coal plants without a planned retirement date, by my count.

Here’s what’s changed over the last year, state by state — including some twists and turns involving cryptocurrency.

Idaho

I’m starting with the deeply conservative Gem State because it offers a striking example of the economic forces at work. Idaho has no requirement for utilities to eliminate fossil fuels — but that’s exactly what the state’s largest electric company is doing.

It’s been almost three years since Idaho Power committed to 100% clean energy by 2045, citing customer demands and the falling costs of renewable energy sources, which are often cheaper than coal. Just last month, the company sped up its plans to ditch coal, pledging to stop buying electricity from Wyoming’s Jim Bridger Power Plant by 2028 and Nevada’s North Valmy plant by 2025.

And while Idaho Power expects to increase its use of natural gas — less polluting than coal but still a fossil fuel — it’s mostly planning investments in solar, wind and batteries, along with transmission lines to get that clean power where it needs to go.

“There’s a strong desire to move toward 100% clean electricity,” Jared Ellsworth, the company’s resource planning director, told me, adding the company is confident it can do so successfully. “We don’t feel like we have to sacrifice reliability or cost.”

Montana

Montana’s Lewis and Clark Station shut its doors on March 31. But coal is far from dead in Big Sky Country.

Anne Hedges, director of policy and legislative affairs at the Montana Environmental Information Center, tells me Colstrip Steam Electric Station is “the most complex [coal] plant in the nation,” and I’m inclined to agree with her. The two generating units have six different owners serving utility customers across nine states, and they disagree on if or when to shut the plant down.

The fight has pitted plant owners based in Oregon and Washington — where state laws require electric utilities to get out of the coal business — against South Dakota-based NorthWestern Corp. and Talen Energy, a subsidiary of New York private equity firm Riverstone Holdings. The battle involves several lawsuits, some focused on legally dubious measures passed by the Montana Legislature and signed by Gov. Greg Gianforte designed to keep Colstrip running beyond an expected closure date of 2025.

“NorthWestern has been doing everything in its power to force the other owners to keep that plant operating,” Hedges said.

Montana is also home to two smaller coal plants.

One of them, Beowulf Energy’s Hardin Generating Station, has found new life powering cryptocurrency “mining,” an energy-intensive process. Beowulf formed a joint venture with Marathon Digital Holdings of Las Vegas, which said in a news release last month that it had “successfully deployed 30,391 top-tier bitcoin miners and completed the construction of its mining facility in Hardin, MT.” After upgrades to the coal plant in November, Marathon produced 34 bitcoin on Dec. 1, the company said.

Hedges compiled data showing that Hardin fired up its generators just 72 days on average from 2017 through 2020, likely due to the poor economics of coal power. But in 2021, the coal plant operated on 236 days in the first three-quarters of the year alone.

“It terrifies me that cryptocurrency could just wipe away climate progress,” Hedges said.

Montana’s other small coal plant, Colstrip Energy LP, has a contract to sell electricity to NorthWestern through June 2024. But NorthWestern has indicated it may not be interested in a contract renewal. The coal plant will be forced to closed if its owners can’t find another customer, according to Lee Roberts, president of Rosebud Energy Corp., which operates the facility.

“We’ve pursued every market we can think of,” Roberts told me. “We’ve made no progress.”

New Mexico

New Mexico is one of several Western states with laws requiring utilities to achieve 100% clean electricity — eventually.

But just like in California, the transition may not be smooth. The Land of Enchantment’s largest utility — Public Service Co. of New Mexico, better known as PNM — is warning that its customers could face rolling blackouts this summer if coal-fired San Juan Generating Station closes as expected in June. Shockingly, PNM says it’ll have a negative reserve margin without San Juan — meaning it won’t have enough power to cover expected electricity demand, let alone the large buffer utilities typically build in.

The power shortfalls could be even worse than anticipated if the entire West bakes in a heat wave like it did in August 2020, when California saw rolling blackouts. If everyone is blasting air conditioning at the same time, there’s less power to go around.

Across the region, “utilities are struggling with the mandate to keep power reliable,” said Seth Feaster, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “You have to keep the power on, or the wrath of your legislature and regulators comes down upon you, like what happened in Texas. And it ends up costing you a fortune, because then they fine you.”

What’s gone wrong in New Mexico? PNM blames several factors, including pandemic-related supply-chain delays that have slowed construction of four solar farms paired with lithium-ion batteries. The utility is also frustrated with the state’s Public Regulation Commission, which it says took far too long to approve those renewable energy facilities. The commission rejected a natural gas plant that PNM had hoped to build, too, among other decisions supported by climate activists and opposed by the utility.

Keeping San Juan open a few extra months “would go a long way toward solving the issue,” said Tom Fallgren, PNM’s vice president of generation. But it would be no easy task, requiring approval from the commission and the plant’s other owners.

New Mexico is also home to Four Corners Power Plant, whose majority owner, Arizona Public Service Co., has pledged to shut it down by 2031. New Mexico regulators recently rejected PNM’s plan to sell its 13% share of the coal plant to Navajo Transitional Energy Co., which is owned by the Navajo Nation, saying the utility hadn’t identified adequate replacement energy sources.

PNM is appealing to the New Mexico Supreme Court, arguing the sale would save customers money. Climate activists say the firm should instead try to accelerate the plant’s closure, rather than selling to a company that might try to keep it open indefinitely.

Colorado

In August, Colorado Springs Utilities powered down Martin Drake Power Plant for the last time. Also last year, the state’s largest utility — Xcel Energy — set deadlines for shuttering several coal plants, including Comanche, Hayden and Pawnee. With other utilities planning to shut down the Craig, Rawhide and Ray Nixon generating stations, Colorado could eliminate coal by 2035.

But some climate advocates want to see Xcel ditch coal not later than 2030, and stop investing in natural gas as a replacement fuel source — a strategy they say does not comport with a Centennial State law requiring big reductions in heat-trapping emissions.

Xcel “really surprised us this year in their lack of leadership,” said Amelia Myers, Western director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

The company has defended its plans, with Alice Jackson — chief executive of Xcel’s Colorado subsidiary — telling the Colorado Sun’s Mark Jaffe, “It comes down to a compromise. We’ve come to a constructive solution for Colorado and our customers.”

Arizona

Arizona Public Service Co. plans to shutter the coal-fired Cholla Power Plant by 2025. Tucson Electric Power says it will stop operating two coal units at Springerville Generating Station by 2032, while phasing down their use substantially before then.

The rest of the story is hazier.

The electric cooperative Tri-State Generation and Transmission has won praise from climate activists for speeding the transition away from coal in other states, but it currently plans to keep burning coal at Springerville indefinitely. And Salt River Project — a Phoenix-area utility — has no plans to shut down its own Springerville unit, with spokesperson Scott Harelson telling me in an email that the unit “is equipped with state-of-the-art emission controls and currently provides economical and reliable energy.”

That doesn’t satisfy climate advocates, who point to research suggesting that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius would require the United States to achieve 100% clean energy by 2035. Activists also aren’t happy that Salt River Project may keep running the coal-fired Coronado Generating Station until 2032, and that it plans to spend nearly $1 billion expanding a gas plant.

The Grand Canyon State is also home to Apache Generating Station, which owner Arizona Electric Power Cooperative has no plans to retire. Interestingly, one of the rural co-ops that buys energy from the coal plant is California’s Anza Electric, which supplies power to a few thousand homes and businesses in Riverside County, in the high desert east of Temecula. Anza is one of a small handful of Golden State electricity providers that still relies on coal, along with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Anza’s general manager, Kevin Short, told me the utility is adding solar and batteries to its system as fast as possible, including as part of a microgrid that can keep the area’s “tiny little downtown” powered five or six hours into the night after a sunny day. Anza’s reliance on the Apache coal plant dropped from about 23% of its energy supply in 2020 to 14% last year, Short said.

“The intention is we need to be done with it,” he said. “I don’t want to be the last coal user standing in the state.”

Wyoming

The Equality State is home to two coal plants without closure dates: Dry Fork and Laramie River stations, each of whose largest owner is Basin Electric Power Cooperative. Spokesperson Andrew Buntrock told me Basin Electric’s energy mix dropped from 85% to 40% coal between 2000 and 2020, although then-general manager Paul Sukut wrote in a 2020 report that the co-op was not planning to abandon coal anytime soon “because we need this generation to maintain reliability for the foreseeable future.”

Then there’s Gillette Energy Complex, the site of several coal plants majority-owned by Black Hills Corp. of South Dakota. The firm hadn’t previously shown much desire to stop burning coal, but it announced plans last year to convert the Neil Simpson II coal plant to natural gas in 2025. Spokesperson Stephanie Dowling tells me Black Hills plans to shutter its other Gillette coal plants — known as Wygen I, II and III — or convert them to natural gas at the end of their “engineered life,” between 2033 and 2040.

Arguably the most interesting Wyoming story involves PacifiCorp, the six-state utility owned by billionaire Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. The company has long defended its coal fleet, which supplies power to some Northern California residents.

But Berkshire said last year it would shutter all its Wyoming coal units, despite state lawmakers’ efforts to save coal. The company plans to stop burning coal at the Naughton plant by 2025, Dave Johnston by 2027, Jim Bridger by 2037 and Wyodak by 2039.

Once again, that doesn’t guarantee a smooth transition. PacifiCorp is battling the Biden administration over haze-forming emissions from Jim Bridger, with Gov. Mark Gordon signing an emergency order to stop the possible shutdown of two coal units after the Environmental Protection Agency declared Wyoming’s air-pollution plan to be out of compliance with the Clean Air Act.

State and federal officials are currently negotiating a settlement, which could result in PacifiCorp agreeing to convert the two coal units to less-polluting natural gas — a desirable outcome for Buffett, since the company was planning to do that anyway.

The Sierra Club isn’t impressed with PacifiCorp’s timeline for ditching coal. Myers called the firm “the worst utility in the West.”

Utah

PacifiCorp is a major player in Utah, too, operating the Hunter and Huntington coal plants. It currently anticipates that Huntington will retire in 2036. Hunter’s future is less certain, although the company currently expects the plant to close in 2042, spokesperson Tiffany Erickson said.

Climate activists say the federal government should have required the two plants to install pollution-control equipment to reduce emissions that lead to hazy air and diminished views in national parks, including Utah’s “Mighty Five.” The Obama administration tried to mandate those upgrades, but President Trump’s appointees gutted the proposed rules — and now Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency is defending Trump’s rollback. The Sierra Club and several other groups are suing the EPA to force the issue.

Erickson told me PacifiCorp believes Utah’s regional haze plan complies with the Clean Air Act. More broadly, the utility has touted its clean energy ambitions, saying in a September news release that it planned to reduce planet-warming emissions 74% below 2005 levels by 2030 and was moving toward “a bold energy future with low-cost, reliable, sustainable power for its customers.”

Elsewhere in Utah, Los Angeles and several other California cities continue to work toward shutting the coal-fired Intermountain Power Plant and replacing it with natural gas turbines, and eventually renewable hydrogen. Climate activists also expect Bonanza Power Plant, which is owned by Deseret Power Electric Cooperative, to close by 2030 under the terms of a legal settlement.

Nevada

Last but not least, the Silver State.

It’s a simple story here. The state’s largest utility, NV Energy — also part of Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway — says it will shut down the North Valmy coal plant by 2025. Nevada’s only other coal plant is operated by Nevada Gold Mines. The company has said it will convert the TS Power Plant to natural gas, although representatives didn’t respond to my email asking if that’s happened yet.

And there you have it: Everything you possibly could have wanted to know about the last coal plants in the American West.

Here’s what else is happening around the region:

TOP STORIES

California is poised to fine Southern California Gas $10 million for working to block climate action. The state’s Public Utilities Commission says SoCalGas repeatedly violated an order to stop spending customer money fighting clean energy policies, and that “such insolence must be accorded a high degree of severity.” Here’s my story, which details the company’s sweeping campaign to protect its business model. SoCalGas has defended its actions, arguing its 1st Amendment rights are at stake. In a separate case involving SoCalGas using ratepayer money to fight other climate measures, the utilities commission on Wednesday proposed fining the company $150,000 — far less than the $255 million recommended by the commission’s own consumer watchdog.

In related news, Los Angeles City Councilmember Nithya Raman introduced a motion that would ban gas hookups in new buildings no later than 2030, with the backing of Mayor Eric Garcetti. Here’s the story from City News Service; most of the policy details still need to be worked out. I’ll have more on this in the next few months. In the meantime, if you’re looking to keep up with local politics during an election year, you might sign up for our City Hall bureau’s brand-new L.A. on the Record newsletter.

“It’s easy to get discouraged when you’re thinking about the whole climate-change issue. But when you look at sports, you see underdogs pulling off amazing things all the time.” As the Winter Olympics got underway in Beijing, The Times’ David Wharton wrote about how skiing and snowboarding are faring in an increasingly snow-starved world. Here in Southern California, this Sunday’s Super Bowl could be the hottest ever played, with temperatures possibly reaching the high 80s, Paul Duginski writes.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

A wealthy Silicon Valley suburb tried to shirk its affordable housing responsibilities by declaring the whole town to be mountain lion habitat, and arguing new duplexes and fourplexes would pose a threat to the iconic species. Mountain lion experts were not amused, saying Woodside’s plan could actually make matters worse by pushing housing construction away from already-developed areas and into wildland habitat, my colleague Liam Dillon reports. The move prompted an immediate outcry, with California’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, basically calling the town’s plan illegal. Woodside officials quickly backed down.

Turlock Irrigation District, a farm water provider in the San Joaquin Valley, is getting a $20-million state grant to test out solar panels covering irrigation canals. Details here from John Holland at the Modesto Bee. You may remember I wrote about this idea last year. If Turlock’s pilot project is successful, solar panels on canals could help the state cut emissions while reducing evaporation, and also limit the land-use battles that have frustrated solar and wind energy development on public lands.

California’s bullet train is now expected to cost $105 billion, up from a previously estimated $100 billion. That’s far higher than the $33-billion price tag California voters were told to expect when they approved funding for high-speed rail in 2008, Ralph Vartabedian reports for The Times. In other public transit news, something odd is happening at BART, aka Bay Area Rapid Transit. The agency has issued a stop-work order to a key engineering firm while it conducts a conflict-of-interest review, Ralph writes.

AROUND THE WEST

A Utah county wants to pump groundwater near the Nevada border to supply growing Cedar City — but tribes, ranchers, environmentalists and rural politicians in both states say the withdrawals would threaten sacred springs and habitat. It’s pretty much a classic Western water conflict, Blake Apgar reports for the Las Vegas Review-Journal. In another interstate battle, the Salt Lake Tribune’s Brian Maffly reports that Oakland may have finally killed Utah’s plan to export coal through the port city.

Central Valley water officials are relying on a study by oil industry consultants to declare that irrigating crops with oil-drilling wastewater is safe. But independent experts say the study has gaping holes, Liza Gross reports for Inside Climate News. Her investigation finds it’s not yet clear if there are health risks from eating food grown with oil industry “produced water.”

Congress appropriated a bunch of money to start paying down the National Park Service’s maintenance backlog. It seems like there’s a need for a big influx of funding to house Park Service employees, too, with Rob Hotakainen reporting for E&E News that many rangers and other workers from Yellowstone to Acadia can’t find homes they can afford anywhere near the parks. In better public lands news, Kylie Mohr reports for High Country News that the cash-strapped Bureau of Land Management will now have a nonprofit foundation to help fund its initiatives, much like the one that has long supported the National Park Service.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

As temperatures continue to rise, Californians could lose air conditioning for roughly one week each summer because the demand for cooling will have exceeded the capacity of the electric grid. So write my colleagues Alex Wigglesworth and Ruben Vives, based on new research led by a Penn State scientist. With the Golden State making big plans to build renewable power facilities and increase energy efficiency, hopefully that future won’t come to pass. But it’s still a reminder of the major challenges ahead. Speaking of which, the California Independent System Operator just projected the state will need $30.5 billion worth of new power lines by 2040, along with 120 gigawatts of new clean energy capacity. Details here from Utility Dive’s Kavya Balaraman.

The suburbs between Denver and Boulder, Colo., were built out of the ashes of the coal industry — so it’s ironic that a long-burning underground coal seam fire may have sparked the late-December Marshall fire, which destroyed more than 1,000 homes. Here’s a moving portrait of the area and its history from Kate Schimel for High Country News. In more positive news, Colorado is getting a bunch of money from the federal infrastructure bill to help contain such coal seam fires, Michael Booth reports for the Colorado Sun. It’s part of $725 million in funding the Biden administration is making available this year to 22 states and the Navajo Nation for reclaiming abandoned coal mines and cleaning up acid mine drainage, as the AP’s John Raby reports.

It’s still not clear when Gov. Gavin Newsom and the California Public Utilities Commission might announce a new plan for the future of net metering, the state’s much-debated rooftop solar incentive program. In the meantime, here are two interesting articles about local solar to tide you over, from Jeff St. John at Canary Media. First, Jeff wrote about how California can make community solar — a sort of middle ground between rooftop and utility-scale — finally take off. Second, a San Diego startup says it has developed a software solution to the “split incentive” problem that’s made it so difficult for renters to go solar.

ONE MORE THING

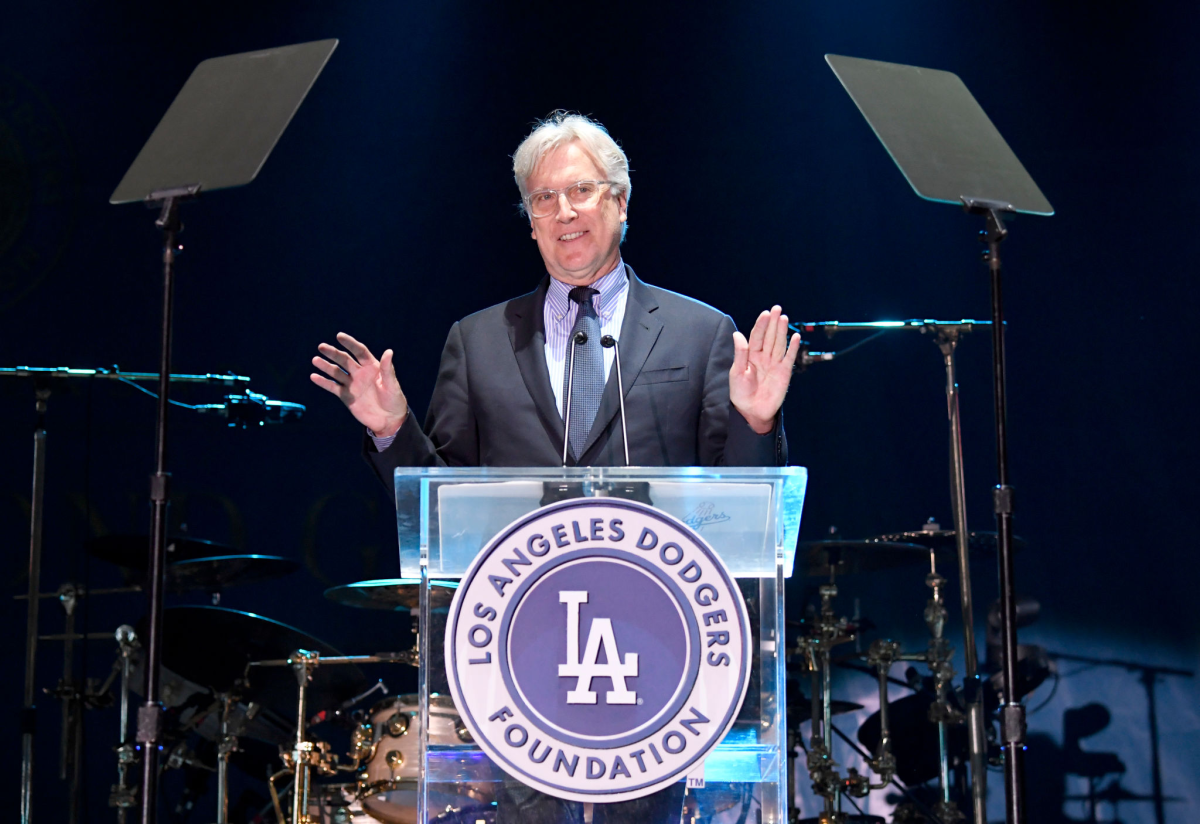

Is Los Angeles Dodgers controlling owner Mark Walter — the billionaire chief executive of financial services firm Guggenheim Partners — secretly amassing land in a Rocky Mountains town for a real-life Galt’s Gulch, the fanciful hideaway for brilliant and successful capitalists in a socialism-plagued world that was imagined by Ayn Rand in her iconic novel “Atlas Shrugged”?

I mean... no, almost certainly not. But Walter has indeed bought up a whole bunch of Crested Butte, Colo., where he and his wife are part-time residents, George Sibley writes in an essay for the Mountain Gazette (more details here from Jason Blevins at the Colorado Sun). And with Walter not discussing his purchases publicly, Sibley can’t help but speculate about his intentions.

Mark, if you’re reading this, send me an email and let me know what’s up. I’m a big Dodgers fan, and I’m curious!

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.