Newsletter: Harry Reid reshaped the West. His environmental legacy is complicated

This is the Jan. 6, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

When Harry Reid retired, New York Magazine ran this headline: “Who Will Do What Harry Reid Did Now That Harry Reid Is Gone?”

I’ve been thinking about that question as Democrats struggle to advance President Biden’s Build Back Better bill, which includes hundreds of billions of dollars in clean energy investments. As the Senate’s Democratic leader, Reid was legendary for brokering deals and holding his caucus together, most famously getting President Obama’s Affordable Care Act across the finish line despite unified Republican opposition. It’s hard not to wonder: If Reid were still in charge, would the climate bill have passed by now?

It was an impossible question to answer even before the Nevada senator died last week from pancreatic cancer.

But Reid’s legacy lives on across Western landscapes. And if you care about the region, you’d do well to study that legacy.

For a primer, check out this documentary produced last year by KCET, “The New West and the Politics of the Environment.” It chronicles Reid’s impoverished origins in the gold-mining town of Searchlight and his many environmental efforts, including:

- Crafting the bill that established Great Basin as Nevada’s first national park, after compromising with Republican officials over the size of the park and working with the Reagan administration to make sure the legislation wouldn’t be vetoed;

- Bringing together the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe and other northern Nevada water users to negotiate a settlement on the Truckee and Carson rivers, which made water available to the tribe to restore Pyramid Lake and save endangered fish;

- Pressuring Nevada’s dominant power company, NV Energy, to agree to an early shutdown of the coal-fired Reid Gardner Generating Station, which had polluted the air breathed by the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians for decades;

- Blocking a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, on public lands about 100 miles outside Las Vegas;

- Working with Republican Sen. John Ensign to support the growth of Las Vegas by passing the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act, which has allowed the city and its suburbs to expand through auctions of public land to the highest bidder, with the proceeds being used to protect and improve access to remaining undeveloped areas around Las Vegas;

- Passing Obama’s stimulus bill, which included $90 billion for clean energy and helped launch the large-scale solar industry;

- Supporting protection of 750,000 acres of northern Nevada wilderness, through a bill that passed the Senate unanimously;

- Helping persuade Obama to create Basin and Range National Monument, and later Gold Butte National Monument.

Those deals made Reid enemies, especially in rural Nevada. In the Truckee River Basin, for instance, farmers were furious to receive less water under the deal Reid facilitated. Critics also slammed the monument designations as federal land grabs.

Some environmentalists, too, were frustrated by Reid’s allegiance to the mining industry, and by his support for a plan to pump groundwater in rural Nevada and send it to Las Vegas via pipeline. After leaving office, he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that water being used on farms in Lincoln County created hardly any jobs, and could instead “be used to flush toilets on the Strip.”

But Reid’s admirers say his talent for dealmaking — and his ability and willingness to use political power for environmental goals — offer a much-needed roadmap for progress, especially as climate change makes the West a more dangerous place to live.

“Reid had this unique combination of optimism that something could be done, but also a pragmatism about the contours or the bounds that could make a deal possible,” said Christian Filbrun, a doctoral student who is studying Reid’s legacy at the University of Nevada, Reno. “Perhaps the old way of navigating the Senate isn’t possible any longer as things become more divisive. But I think his career can still be viewed as a model to broker these deals and bring groups together.”

The West faces no shortage of climate challenges that demand collaboration. Long-term aridification is sapping the Colorado River. Wildfires have become a year-round threat. Mining for metals crucial to the clean energy transition is a burgeoning source of tension. Coal miners, ranchers and farmers are pushing back as urban growth and changing economics upend their way of life.

Harry Reid could not have solved those problems alone. But Jon Christensen thinks examining his legacy is a good starting point.

Christensen is an environmental historian and UCLA professor who spent more than a decade as a journalist in Nevada, where he followed Reid’s career closely. He produced the KCET documentary on the Nevada senator and was featured in it prominently.

“Outside of the coastal states, the American West is a purple region,” he told me. “The path that Harry Reid forged for compromise with Republican colleagues, with conservative county commissions — that’s what’s going to be needed.”

When I asked Christensen which politicians might pick up Reid’s mantle, though, he had trouble naming any Republicans. He acknowledged that moderate Republicans have “become an endangered species” and said Democrats who want to solve the West’s environmental crises should build strong party infrastructure at the state level — much as Republicans have done.

Reid was good at that too. His political machinery not only got him reelected during 2010 midterms otherwise dominated by the GOP but also helped deliver the Silver State for Hillary Clinton and Reid’s handpicked Senate successor, Catherine Cortez Masto.

The senator wasn’t afraid to cajole and threaten. He helped the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians build the nation’s first large solar farm on tribal lands, for instance, by calling then-Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and suggesting the city buy the power. When NV Energy wanted to build new coal plants, Reid intervened with a hedge fund planning to finance construction.

“I called a hedge fund and I told the guy, ‘Look, you back away from that coal plant or I will get even with you. I don’t know what I’m going to do, but I will figure something out,’” Reid recalled in the KCET documentary.

That kind of story makes me wonder how Reid might have handled the conflicts between renewable energy development, habitat conservation and tribal rights that are becoming increasingly common on Western landscapes, including in his state.

Just this week, a federal judge temporarily blocked construction of a geothermal power plant on public lands in northern Nevada, agreeing with the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe that the project could threaten a sacred spring, as Jeniffer Solis reported for the Nevada Current. Would Reid have agreed with the tribe and pressured the city of L.A. — which is slated to buy the power — to back out of the geothermal plant? Or would he have gotten Congress to pass a bill allowing the project to move forward?

What about a solar farm on Nevada’s Mormon Mesa, which was scrapped by the developer after critics said it would disrupt the experience of viewing a remote piece of desert land art, Michael Heizer’s “Double Negative”? Reid pushed for Basin and Range National Monument in part to protect another Heizer sculpture, known as “City,” from a railroad line that would have brought nuclear waste to Yucca Mountain. Would Reid have seen the Mormon Mesa solar farm as a threat, or as a public good?

Here’s what I struggle with, personally: In an era of environmental crisis, when is compromise acceptable?

Scientists say planet-warming emissions need to be cut roughly in half by the end of this decade, then flattened to net-zero by midcentury. Biodiversity loss continues at an alarming and accelerating rate, with many species being pushed toward extinction. Tribal nations and communities of color are rightfully demanding the clean water, air and soil they have long been denied.

Patrick Donnelly, Nevada director of the Center for Biological Diversity, sees Reid’s environmental legacy as a mixed bag. While Reid protected vast swaths of wilderness, killed coal plants and helped restore Pyramid Lake — for which he should be commended, Donnelly told me — he also blocked mining reform and supported the controversial Las Vegas water pipeline.

Donnelly is especially worried about Reid’s template of allowing sprawling suburban development in exchange for wilderness protections. The Senate leader pioneered that tradeoff in the Las Vegas Valley nearly a quarter of a century ago. Its legacy continues to this day, with Cortez Masto introducing a bill in the Senate that would conserve about 2 million acres in Clark County while allowing the Las Vegas metro area to expand outward toward the California border, gobbling up public lands along the way.

It’s no secret that suburban sprawl can exacerbate the climate crisis, leading to more driving and more tailpipe emissions. Donnelly would much rather see Las Vegas — and cities across the West — focus on dense infill development and public transit.

“The climate crisis is a screaming emergency that demands a new way of doing business,” Donnelly said. “I don’t want to condemn the Reid model of making deals ... but we’re in a new time now, and at least on the environmental side of that equation, the climate crisis throws the whole dealmaking balance out of whack. Climate should be the lens.”

“The Nevada Harry Reid came up in was a very different place at a different time,” he added. “I don’t doubt that you had to make some serious deals to get things done on the environment 30 years ago here. I’m really more interested in the legacy moving forward. Are we going to learn from the consequences of all that? Or are we just going to say, ‘Rah rah, this was great?’”

It’s impossible to know how Reid would have navigated the West’s current and future challenges. But it’s possible to guess what political calculus might have informed his decisions. His deals often left farmers and ranchers feeling like they were on the losing end — and he seemed to accept that, especially if it meant Native Americans or other marginalized groups benefited.

“You can call it Reid’s pragmatism that he recognized that Nevada was shifting and he didn’t need the rural vote anymore,” Filbrun said. “Whether it was pragmatism or bravery that he could weather the storm is up for interpretation.”

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

The Marshall fire tore through Colorado suburbs between Denver and Boulder over New Year’s weekend, destroying nearly 1,000 homes and other buildings. No deaths have been reported, but two people are still missing. The blaze is unfortunately teaching Coloradans a lesson that many Californians have learned: The wildland-urban interface is huge, and just because you don’t live in the forest or the mountains doesn’t mean you’re safe, as Sam Brasch writes for CPR News. The Washington Post also has a lucid rundown of how climate change created the conditions for such an awful winter firestorm.

Although the Golden State has seen blazes like Colorado’s, that doesn’t mean all Californians are coming to terms with the new reality we face. In a searing essay for ProPublica and the New York Times Magazine, Elizabeth Weil writes that the California we know and love is actually gone, and we need to confront the one we’ve got. That means fireproofing homes, pulling back from the wildland-urban interface and hurrying to reduce climate pollution. Blaming the problem on forces outside our control — like the argument that arson is getting worse, which my colleague Hayley Smith largely debunked — is not going to solve anything.

A Pacific Gas & Electric power line ignited the Dixie fire, which burned nearly 1 million acres last year. Here’s the story from The Times’ Gregory Yee, who writes that investigators determined PG&E was responsible for the second-largest fire in California’s recorded history. In related news, federal judges rejected a challenge by attorney Michael Aguirre to the $13.5-billion wildfire liability fund approved by state lawmakers, which critics derided as a bailout of PG&E and other utilities. California utilities have also faced criticism for trying to prevent ignitions by shutting off power during fire weather — but in Washington state, people are frustrated that utilities aren’t shutting off power more often as fire danger grows, Rebecca Moss reports for the Seattle Times.

WATER IN THE WEST

California has instituted water-wasting rules similar to those from the last drought, with fines of up to $500 for violators. No more hosing down driveways, overwatering lawns or washing cars without a shutoff nozzle, if for some reason you’re still doing that stuff, my colleague Ian James reports. Officials approved the new rules even after a series of storms that brought Sierra snowpack to 160% of average for this time of year and set rainfall records across the L.A. area. Even with all that water, the next few months will determine whether the drought continues or comes to an end, The Times’ Hayley Smith and Paul Duginski report.

Another positive from all the snow: California should have more hydropower this summer, and less likelihood of rolling blackouts. That said, a return to dry conditions over the next few months could limit the energy windfall, Rob Nikolewski notes for the San Diego Union-Tribune. There’s already enough water in Lake Oroville that hydroelectric generation has resumed after a five-month shutdown, but the plant is nowhere near full capacity, Kurtis Alexander reports for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Even with all the rain and snow, California is throttling back pumping from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta — the heart of the state’s water delivery network — to protect the Delta smelt. Yes, this is the endangered fish that Ted Cruz said goes well “with cheese and crackers” in an appeal to San Joaquin Valley farmers who don’t want to see water deliveries reduced. The Sacramento Bee’s Ryan Sabalow and Dale Kasler explain what’s going on. They also write that nearly all juvenile winter-run salmon died during the hot, dry summer on the Sacramento River last year, with just 2.6% of the endangered fish surviving.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

On a United Airlines flight from Chicago to Washington last month, one of the engines exclusively used cooking oil — a first. It’s one of the options for airlines targeting net-zero emissions by 2050, my colleague Hugo Martín reports. But some clean energy advocates are skeptical that cooking oil is a sustainable fuel. New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham is facing similar criticism over her plan to make the state a hydrogen hub, Scott Wyland and Daniel Chacon report for the Santa Fe New Mexican.

Humboldt County was once the center of California’s lumber industry. Now it wants to be the offshore wind capital of the West Coast, Emma Foehringer Merchant writes for Inside Climate News. That would require major upgrades to the Port of Humboldt, to help it handle wind turbine blades longer than football fields and towers nearly the size of the Washington Monument. But funds from California and the Biden administration, which both want offshore wind, could help make it happen.

Idaho Power says it will phase out coal by 2028 and add huge amounts of solar, wind and battery storage in its quest for 100% clean energy by 2045. The utility company plans to exit from Wyoming’s Jim Bridger coal plant by 2028 and from Nevada’s Valmy coal plant three years earlier, the AP’s Keith Ridler reports. In other potentially positive news for clean energy, Sen. Joe Manchin III voiced support for at least some of the Build Back Better legislation he’s been blocking, telling reporters, “The climate thing is one that we probably can come to agreement much easier than anything else,” per Jeremy Dillon at E&E News.

AROUND THE WEST

The merger of two gold mining giants has had major consequences for the remote northern Nevada community of Elko. Employees say the consolidated company has made life worse for workers who have nowhere else to go, in part through anti-union tactics, and Native American tribes are concerned about the company’s plan to expand gold mining on their ancestral lands, as Nick Bowlin and Daniel Rothberg report in a fascinating deep dive for High Country News and the Nevada Independent.

A plan to mine antimony in Idaho’s Salmon River Mountain has prompted objections from the Nez Perce tribe, who say the project would decimate salmon habitat and violate their treaty rights. A Bill Gates-backup startup would use the antimony to manufacture liquid-metal batteries that haven’t yet proved their effectiveness in the real world, Jack Healy and Mike Baker write for the New York Times. In neighboring Washington state, meanwhile, Gov. Jay Inslee vetoed a section of a landmark climate law that would have allowed tribes to block energy projects that would harm sacred sites, Sarah Sax writes for High Country News.

Southern California ended the year with yet another sewage spill. Beaches were closed on New Year’s Eve as a result, my colleague Anh Do reports; as much as 7 million gallons spilled, with officials citing the failure of an aging sewage line in Carson that was due to be replaced in less than a year, James Rainey reports. In other sewage news — yes, there’s more — El Segundo residents have sued the city of L.A. over last summer’s spill from the Hyperion plant, saying they were exposed to hydrogen sulfide gas, Hayley Smith reports. In better news, Hayley also reports that the Orange County offshore oil spill is now fully cleaned up.

ONE MORE THING

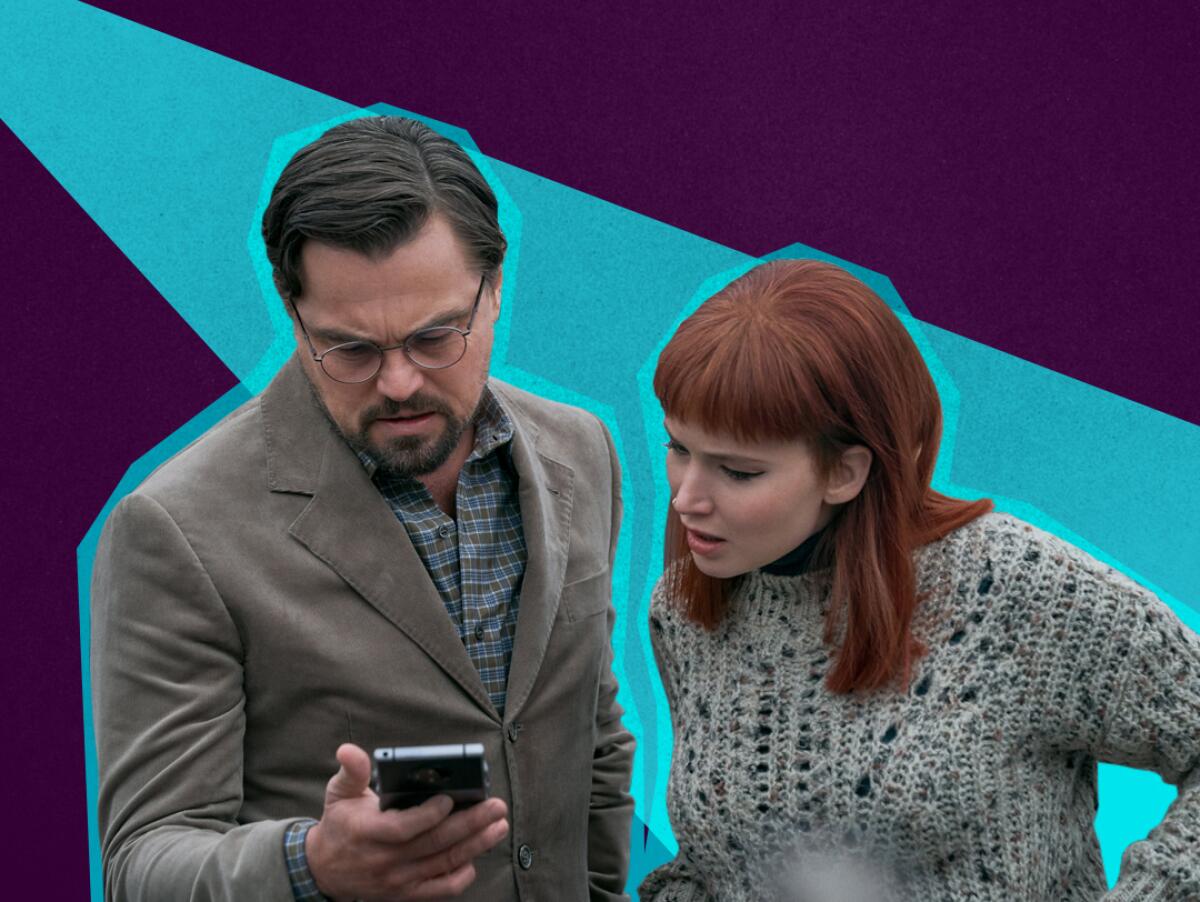

I spent New Year’s Eve watching the Adam McKay film “Don’t Look Up,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence, in which a meteor heading straight for Earth serves as a metaphor for society’s failure to tackle the climate crisis. I wouldn’t say I enjoyed it, exactly — McKay’s criticism of our collective inability to pay attention to impending doom hits painfully close to home — but it’s an excellent, thought-provoking film that I’d recommend. It’ll make you cringe, but it also offers some good laughs.

I’d say the most important thing about “Don’t Look Up” is that it’s gotten so many people talking about global warming. My colleague Ryan Faughnder — who writes our Wide Shot newsletter, which you should definitely sign up for if you have any interest in the entertainment industry — notes that “Don’t Look Up” was the No. 1 movie worldwide on Netflix after its release.

“There’s surely a preaching-to-the-choir aspect to ‘Don’t Look Up.’ But the response to the film shows that there’s at least some appetite for entertainment that directly tackles an issue that, to many, feels intractable,” Ryan writes. Hollywood has had all sorts of trouble telling compelling stories about climate change, he adds, and this film “could break the ice, so to speak.”

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.