Review: The roots of the 1963 March on Washington

Though the post-racial world has yet to materialize, there’s no denying this country has changed some over the last half a century, with an African American family living in the White House and a 30-foot-high statue of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on the Washington Mall.

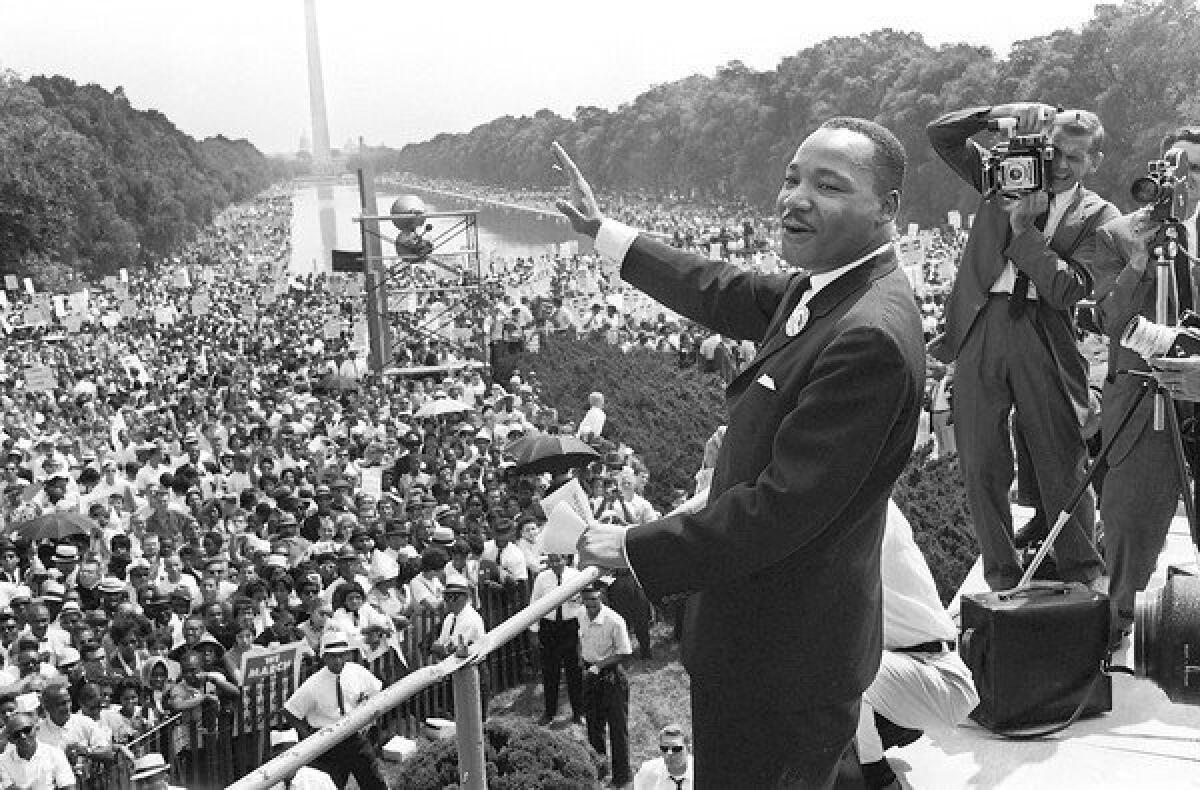

It was not far from that statue that King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, to a quarter of a million people, on the occasion of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Parts of that speech and other images from the day are common currency in documentary films, though usually in the context of some larger, longer story – about King or the civil rights movement or Bob Dylan or any of the other threads to which it’s connected.

In such cases, the event appears full-blown and fully peopled, certified and sealed by history: a thing we think we know. By contrast, “The March,” which airs Tuesday on PBS on the eve of the 50th anniversary of that gathering, tells the story of how it came to be and who made it happen and takes us back before the buses and the trains and the chartered planes arrived from every corner of the country, when no one knew whether it would work, or go bad, or what.

PHOTOS: Hollywood Backlot moments

By 1963, things in the civil-rights movement were coming to a head. In June, Alabama Gov. George Wallace attempted bodily to prevent two black students from registering at the University of Alabama, until President John F. Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard to remove him. Kennedy went on TV afterward to call on Congress “to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law”; hours later, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in Mississippi. At the same time, King was attracting larger crowds wherever he went; the time was ripe for a large, nationally inclusive action.

King’s speech has come to stand for the march, but he was not its only voice or its architect.

That credit goes to A. Philip Randolph — a founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who had had the ear of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and organized Washington marches in the 1940s and ‘50s, and had been advocating for a new one — and his frequent associate Bayard Rustin. A King advisor since the 1955-56 bus boycott in Montgomery Ala., Rustin (a leader in the fight to desegregate interstate bus travel, jailed during World War II as a conscientious objector, gay — and out) was the one who schooled him in Gandhian nonviolence. (“Worth a documentary of his own,” I thought, and then discovered that one exists, the 2003 “Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin.”)

Director John Akomfrah does a good job of giving context to the day, with many (if not most) key surviving participants recalling the march and what it took to make it happen.

These include field organizer Norman Hill, who traveled the country drumming up interest and support; Rustin aide Rachelle Horowitz; CBS correspondent Roger Mudd, on his “first major assignment,” nervously consuming “Coke and Tums” and throwing up in the bushes; Hollywood liaison Harry Belafonte (“Everywhere you looked, there were these nuggets of celebrity”); and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee co-founder John Lewis (then a 23-year-old activist, now a congressman), forced at the last minute to remove a portion of his speech in which “I suggested that if we did not see meaningful progress the day may come when we’d be forced to march through the South the way Sherman did, nonviolently.” (Still, he did use the word “revolution.”)

When it comes to the day’s central oration, Akomfrah can’t quite leave King alone, laying in music below him — not the usual sentimental suet, at least, but a distraction and a distortion nonetheless; those words need no accompaniment. And here and there he processes an image for dramatic (and sometimes confusing) effect.

But these are bumps in an otherwise well-laid road. He puts you in the place and time. Color footage — much of it clearly home-movie footage, from an era when news footage was still often in black and white — brings the past closer.

Kennedy wouldn’t survive the year. But the bill he called for in June was signed into law the next July as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

------------------------------

‘The March’

Where: KOCE

When: 9 p.m. Tuesday

Rating: TV-PG (may be unsuitable for young children)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.