Sid Caesar, an appreciation: Making light of civility’s fragility

Comedian Sid Caesar, who died Wednesday at the age of 91, was a giant and genius of television. He came into the medium, in 1949, when it was still molten. He helped shape TV comedy, even as TV, with its new technical demands and advantages, shaped his work.

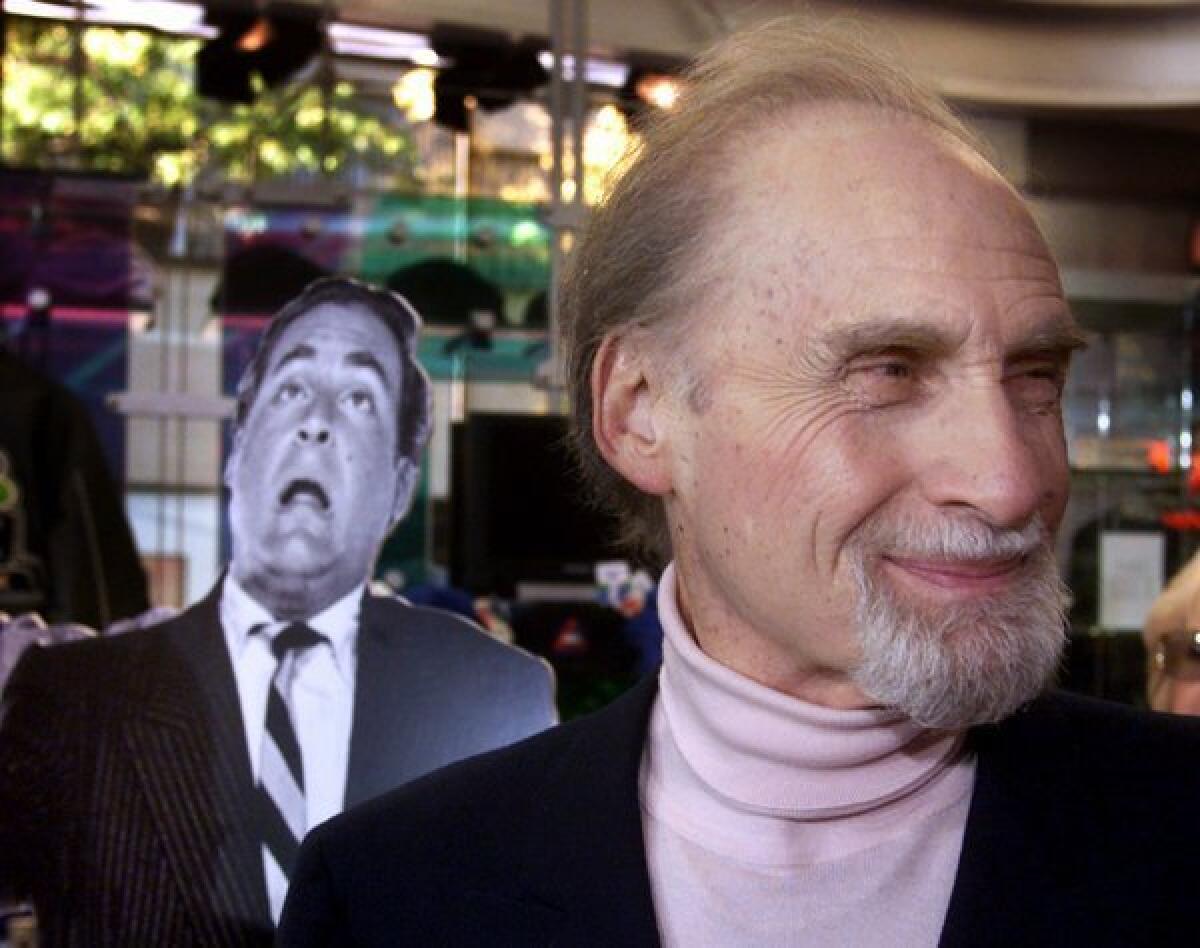

Milton Berle, the man called Mr. Television, had started in TV the year before; but Berle, 14 years Caesar’s senior and in vaudeville since age 12, was already an old pro. Caesar, whose television debut was in fact on Berle’s “Texaco Star Theater,” was a fast-rising newcomer, much of whose previous work had been under the auspices of the Coast Guard. (His first film was the 1946 Coast Guard revue “Tars and Spars.”) He was 26 and making a splash on Broadway in “Make Mine Manhattan,” when his own first series, “Admiral Broadway Revue,” a short-lived precursor to the celebrated “Your Show of Shows,” went on the air.

Tall, dark and handsome, with an elastic, soft-featured face, Caesar had been a musician before he became a comedy star -- a saxophone player, and a serious one. (He was hoping to study in France until the war intervened. He could sing too.) Indeed, his comedy is exceptionally musical, as in his double-talk routines, where he sounds to be speaking a foreign language but isn’t. And there were pantomimes performed to Grieg (as a pianist) and Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (an arguing couple, with Nanette Fabray). But he also possessed an unparalleled sense of pitch and dynamics and tempo; his show’s sketches had a symphonic rise and fall.

PHOTOS: Sid Caesar | 1922 - 2014

He is remembered as the leader of a quartet. Accompanying him in “Your Show of Shows” were Carl Reiner (also a writer), Howard Morris and Imogene Coca. (Fabray replaced Coca in “Caesar’s Hour.”) They formed a core group, a comedy band that, undissipated by a larger ensemble, understood one another on a psychic level. They had speed and daring and youth; they were reckless within the bounds of a strict discipline.

The brilliance of that core ensemble aside, there’s never any question, in any of Caesar’s series, whose show it is. He has the authority of a star, even when he is the buffeted object of chaos in a sketch and not its generator. He has volume and power and presence. Mel Brooks, whom he once dangled out an 18th-floor hotel room when Brooks said he’d like a little air, called him “not only the funniest comic, but also the strongest comic in the world.”

Though the shows were performed in large spaces -- not a TV studio, but a legitimate theater -- the sketches can seem quite intimate, with the camera working in close to catch the pinball play of Caesar’s features. The comedy was at times broad and theatrical and often slapstick, but it was also sharp and perceptive about character and, for want of a humbler word, civilization -- anticipating the more obviously learned satire of Nichols and May or Stan Freberg while not forsaking the pratfall or the funny face. “It remains an island of engaging literacy in TV’s sea of mediocrity,” New York Times critic Jack Gould wrote of “Your Show of Shows” in 1952.

PHOTOS: Celebrities react to Sid Caesar’s death

The show had an urban, specifically New York energy, and even more specifically a New York Jewish energy -- which, like “Seinfeld” a few generations later, translated west of the Hudson and north of the Harlem River. Morris and Reiner were both from the Bronx. In his writer’s room were Brooks (from Brooklyn), Danny and Neil Simon (the Bronx), and Mel Tolkin, born in a shtetl near Odessa, Russia. (Larry Gelbart came from Chicago and Lucille Kalen from L.A.; toward the end of the decade, there was Woody Allen, born in the Bronx and raised in Brooklyn.) Caesar himself came from blue-collar Yonkers, just north of the Bronx, where his parents ran a 24-hour restaurant.

He could be volatile. He struggled with alcohol and depressants. As early as 1956, he wrote in Look magazine of hiding behind his characters -- unlike Berle, who most always played Berle on his show, Caesar was almost always other people. “Offstage, with my real personality for all to see, I was a mess,” he wrote. He would lose his temper sometimes, he later told an interviewer, “because I was holding things in all the the time.... You don’t pick at the little things. When somebody’s creating something you don’t pick at it, you let it develop.”

He believed in working hard and respecting the job -- all the jobs it took to put on a TV show, “from the cameramen to the people who cleaned up.” He was not a perfectionist, exactly, because live television is the enemy of perfection. Or rather, perfection in live television is not a matter of flawless execution of a preconceived idea, but of being successfully present in the moment. Caesar forbade cue cards or teleprompters on his set, because they drew their eyes out of the scene. “I said, ‘Know it,’” he later recalled. “Because when you know it you don’t have to look at the cards... Because the eyes are the soul. You act with your eyes.”

PHOTOS: The funny faces of Sid Caesar

Perhaps not coincidentally, the implied point of many of his sketches -- such sketches as remain available to see, anyway -- is that civilization is always on the point of breaking down, that all it takes to crack the thin veneer of human politesse or custom is to be one sandwich short at a board meeting, or to be sitting in the wrong seat at a movie theater. A sketch in which Caesar returns home to wife Coca on her birthday devolves into a 12-minute argument that plays like a comic “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

Many today will know him best not for a television but a movie performance. (No, I’m not talking about “Grease.” And, no, I’m not talking about “Grease II,” either.) In “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World,” Caesar -- hired as a substitute for fellow video pioneer Ernie Kovacs, who had died in a car crash -- is paired with Kovacs’ widow, Edie Adams. Berle is in the picture too, along with Phil Silvers -- fellow superstars of the preceding decade’s TV. Extracted from the film, the scenes in which he and Adams are locked in the basement of a hardware store -- from which Caesar, in escalating fits of self-injury seeks to free them -- have the shape of one of his sketches, reason collapsing into fury, order into disorder.

He would continue to show up in films -- Brooks put him in “Silent Movie” and “History of the World, Part I,” while the 1973 “Ten from ‘Your Show of Shows’” theatrically repackaged sketches from the series -- and on television. In 1983, he guest-hosted, and was made an honorary cast member of, “Saturday Night Live,” a program created very much in the image of “Your Show of Shows” (which also went live on Saturday night). Even had you not lived in the flush of his fame, there is a good chance you would have seen him work. And any casual student of early television would understand that he had been force to reckon with.

[email protected]

Twitter: @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.