‘American Idol’ became a big star, but now it has been voted off

In the summer of 2002, a new singing contest with a distinctly patriotic title premiered on Fox with little fanfare. “American Idol” took the worn format of the talent search and within months became an unstoppable force, vaulting to the top of the Nielsen ratings by its second season.

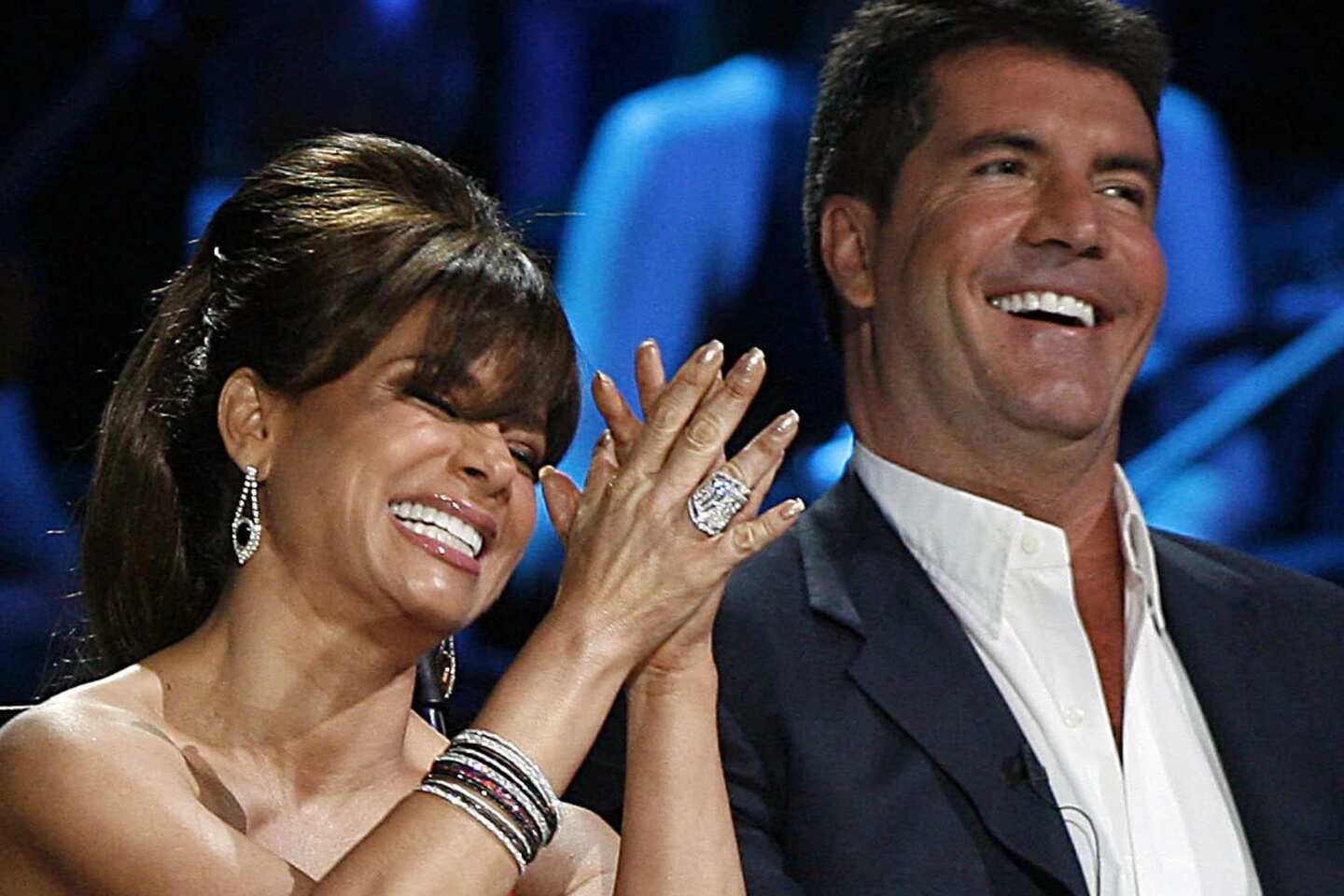

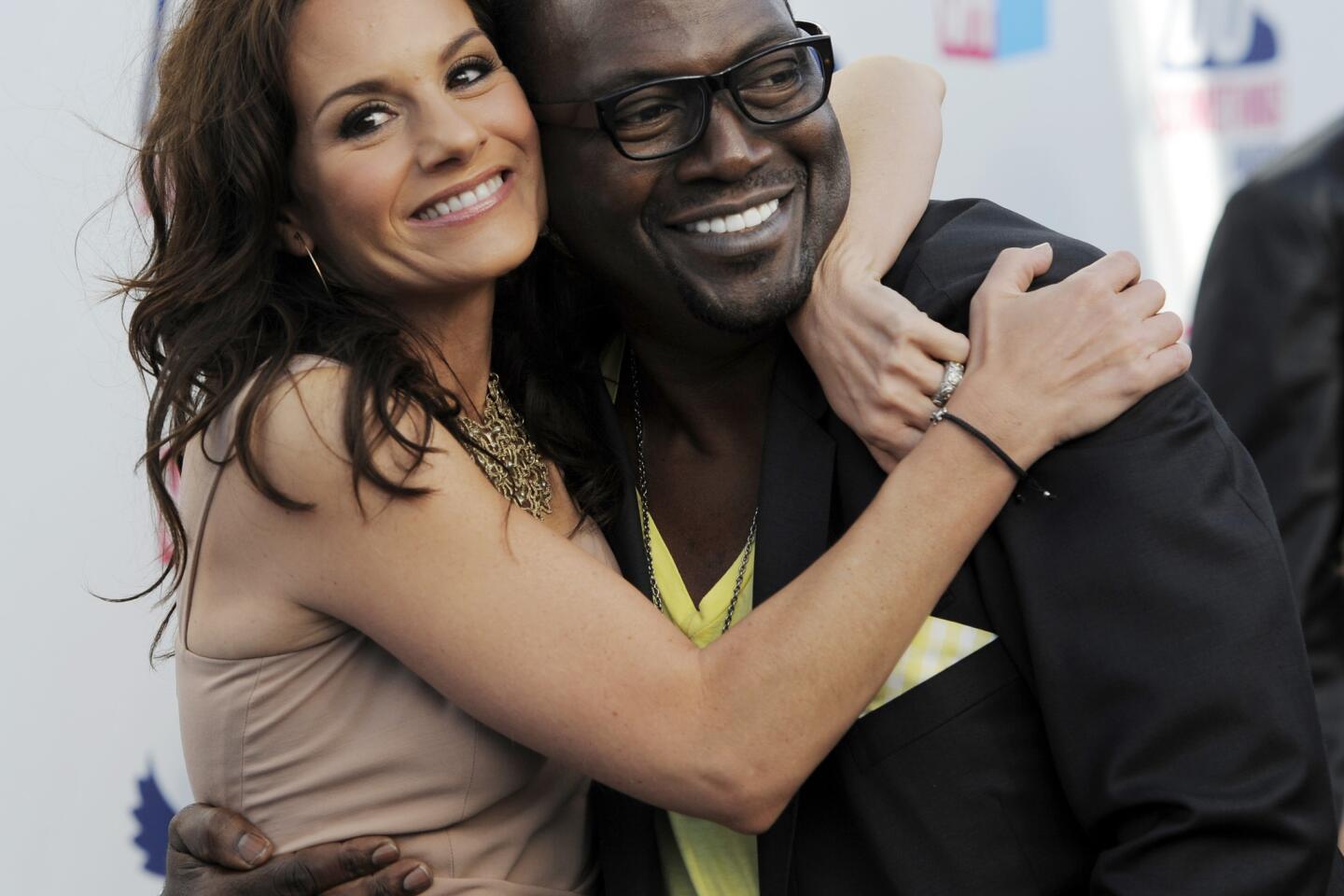

The show’s success hinged on two key factors: the drama at the judges’ table, where British record executive Simon Cowell mixed it up with ‘80s pop icon Paula Abdul and bassist Randy Jackson, and the competition factor, heightened by phone-in voting that let viewers have a say in which singers survived or were eliminated. The show exploited suspense almost to the point of cruelty, leaving aspirants hanging until the last minute, with losers obliged to sing their farewell.

The result? Cowell became a household name and “Idol” became the most dominant force in prime-time reality programming, giving Fox, the once-upstart fourth network, the No. 1 show for a record-breaking eight consecutive seasons.

“If somebody would kill that show, I’d really appreciate it,” CBS boss Leslie Moonves told a media conference in 2008.

Now the singing competition is about to become a cultural relic of the early years of the 21st century, when millions of families once clustered around the TV twice a week to watch it.

After January’s Season 15 premiere was seen by just 10.9 million total viewers, the lowest tally since the show premiered in 2002, “Idol” will go off the air Thursday with a two-hour finale that will crown the 15th-season winner and serve as a retrospective for one of the most popular programs in television history.

At its height in 2006, “Idol” hit a record average of 31.1 million total viewers per week, and its January 2006 premiere logged 37.4 million viewers. It remained TV’s No. 1 show through the 2010-11 season.

“Idol’s” endurance was all the more amazing given that it took place during a time that saw the explosion of YouTube and streaming, on-demand programming.

“The show demonstrated that network television can indeed be relevant if the programming can connect with the audience,” said Jeffrey McCall, a media studies professor at DePauw University.

In addition to spawning competitors — including rival singing show “The Voice,” which is still a hit for NBC — “Idol” proved that live musical performance can attract a big audience on the night it airs, as opposed to scripted series that viewers increasingly watch at their convenience on a DVR or streaming service. NBC and Fox have since launched a cottage industry in live musicals such as “The Sound of Music” and “The Passion,” respectively both of which starred former “Idol” contestants. And “Idol” was — with the exception of a few bleeped curse words — family-friendly, which helped secure its place in living rooms across the country.

“Idol” “was maybe the beginning of what we now call ‘event television,’ ” said Bill Carroll, senior vice president at the Katz Television Group in New York.

Its influence extended to the struggling music industry as well. “Idol” has repeatedly delivered on a promise to find the next generation of pop superstars, with winners Kelly Clarkson and Carrie Underwood each selling tens of millions of records and Jennifer Hudson, the No. 7 finisher from Season 3, going on to a successful music career as well as an Oscar win for “Dreamgirls.”

Unfortunately for Fox, though, “Idol” itself proved not nearly as durable as other reality hits such as “Survivor” and “The Amazing Race.” Its demise was hastened by competition, changing audience tastes and some perhaps ill-advised changes to the format.

“The Voice” premiered on NBC in 2011 and quickly became a major hit, siphoning some of “Idol’s” core young audience. Music fans, meanwhile, moved away from the bubble-gum pop of the early 2000s often favored by “Idol” contestants and embraced electronic dance music (EDM), hip-hop and other trends not easily transferred to a singing-contest format. “Idol” producers began indulging in gimmicks designed to keep viewers from straying, such as dramatic last-minute “saves” (introduced in Season 8) that allowed a judge to keep a favorite from being booted.

None of this was foreseeable in the summer of 2002, when “Idol” premiered to little fanfare as a Fox summer show.

The series was adapted from “Pop Idol,” a British singing show created in 2001 by Simon Fuller, the impresario who had shepherded the 1990s vocal group Spice Girls.

At the time, reality imports from the United Kingdom were the rage in American TV. ABC had found an enormous hit in “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?,” an Americanized version of a British quiz show. NBC enjoyed a brief hit with “The Weakest Link,” another U.K. game format.

“Idol” was the biggest of all. Fox picked up the show after Rupert Murdoch, boss of parent company News Corp., heard a rave for the British show from his daughter Elisabeth.

The initial lineup offered little promise. Cowell, a successful British record executive, was brought over from “Pop Idol,” but Americans had no idea who he was. Paula Abdul, another judge, was a hit maker from a 1980s time capsule, as well as a former choreographer for the Laker Girls and music videos. The third judge, Randy Jackson, was a bassist and producer virtually unknown outside the music business. Overseeing it all were a pair of no-name hosts, Ryan Seacrest and Brian Dunkleman (the latter left after Season 1), as well as another British expatriate, Nigel Lythgoe, as executive producer.

But “Idol” quickly caught on by retrofitting an old format — the talent hunt — for a new era.

“We’ve had [talent competition shows] over the years, even going back to most recently ‘Star Search,’” Carroll said. But “Idol” “was one of the first shows to use both social media and … there was a tie-in with telephone [voting]. It was the first to use interactivity as part of what was taking place.

“Basically these competition shows are the new variety shows on television,” he added.

“Idol” squeezed every last bit of drama and comedy from the format. Producers focused attention on the young performers’ personal lives and struggles, starting with Season 1 winner Clarkson and her runner-up, Justin Guarini. Each season started with a cattle call of delusional or comically untalented aspirants whose bids for stardom were played for laughs. William Hung, Larry “Pants on the Ground” Platt and other contestants enjoyed brief flings with fame due to their against-all-odds auditions.

Abdul supplied endless high jinks at the judges’ table, often appearing overwrought when calming tearful contestants. Cowell and Seacrest strove to top each other with on-screen put-downs.

Viewers responded — and so did advertisers.

“Idol” became one of the top ad buys on TV, by 2009 fetching the astronomical sum of more than $600,000 for a 30-second spot. There were lucrative partnerships with Coca-Cola (Cowell sipped from a big red Coke cup) and Ford (the kids appeared in bespoke car ads that ran during the program).

Meanwhile, “Idol” was, as advertised, minting new music stars, even though many traditionalists lamented its power, which they believed was being used to promote bubble-gum records.

“It brought us back to a period of pop packaging,” said Jonathan Taplin, a former tour manager for Bob Dylan and the Band and now a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. “With the exception of a Kelly Clarkson or someone like that, most of these people were straight out of the imagination of Simon Cowell. Those kinds of people were not interested in artistry; they were interested in a package that would sell.”

But it wasn’t long before “Idol” itself stopped selling so well to audiences. Now, the show is ending with more of a whimper than a triumphant crescendo.

Abdul exited in 2009, followed by Cowell, who jumped to his own Fox show, the since-defunct “The X Factor,” a year later. “Idol” was thus robbed of its most recognizable voices (Jackson stayed until 2014; host Seacrest is the only on-air personality to remain through all 15 seasons).

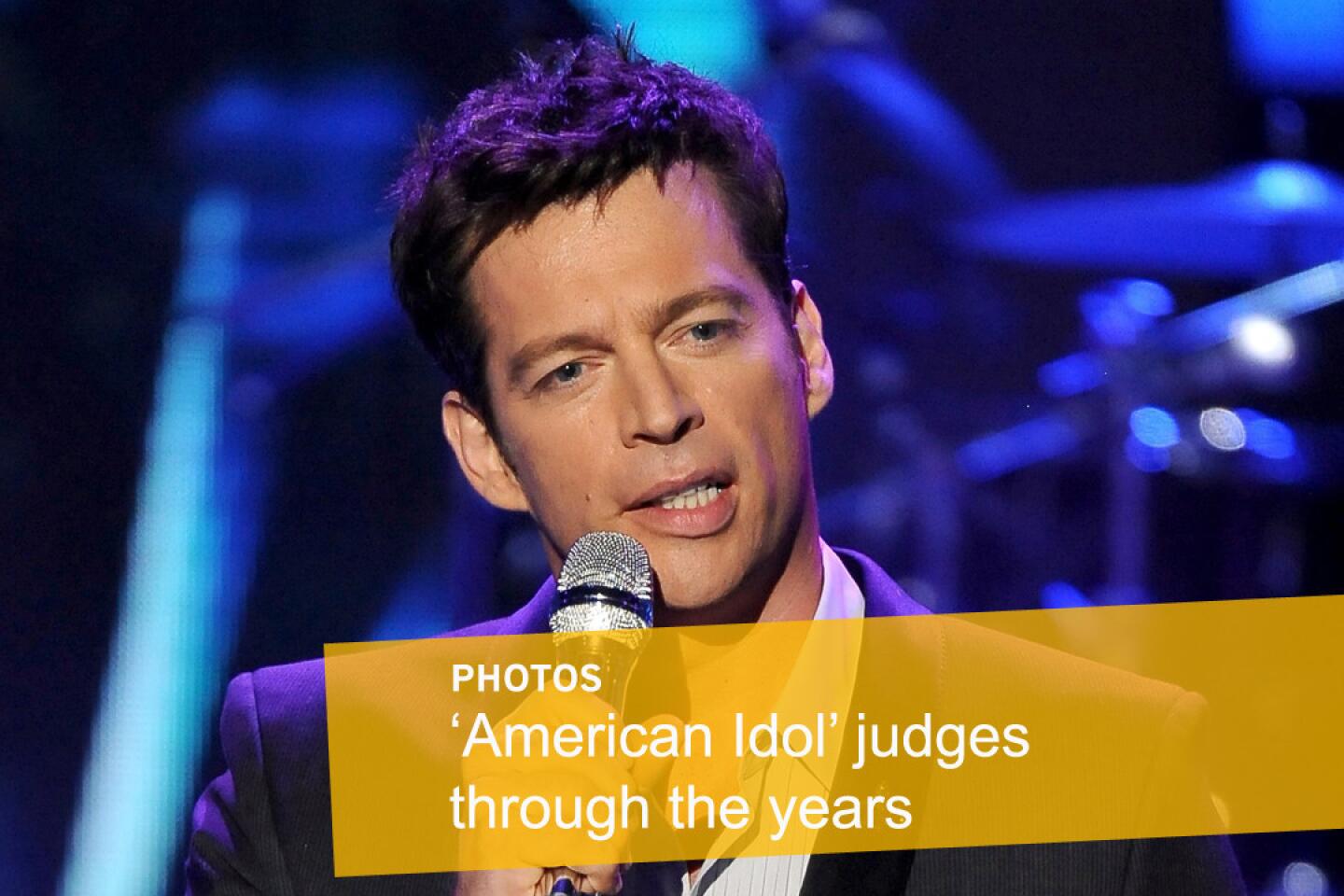

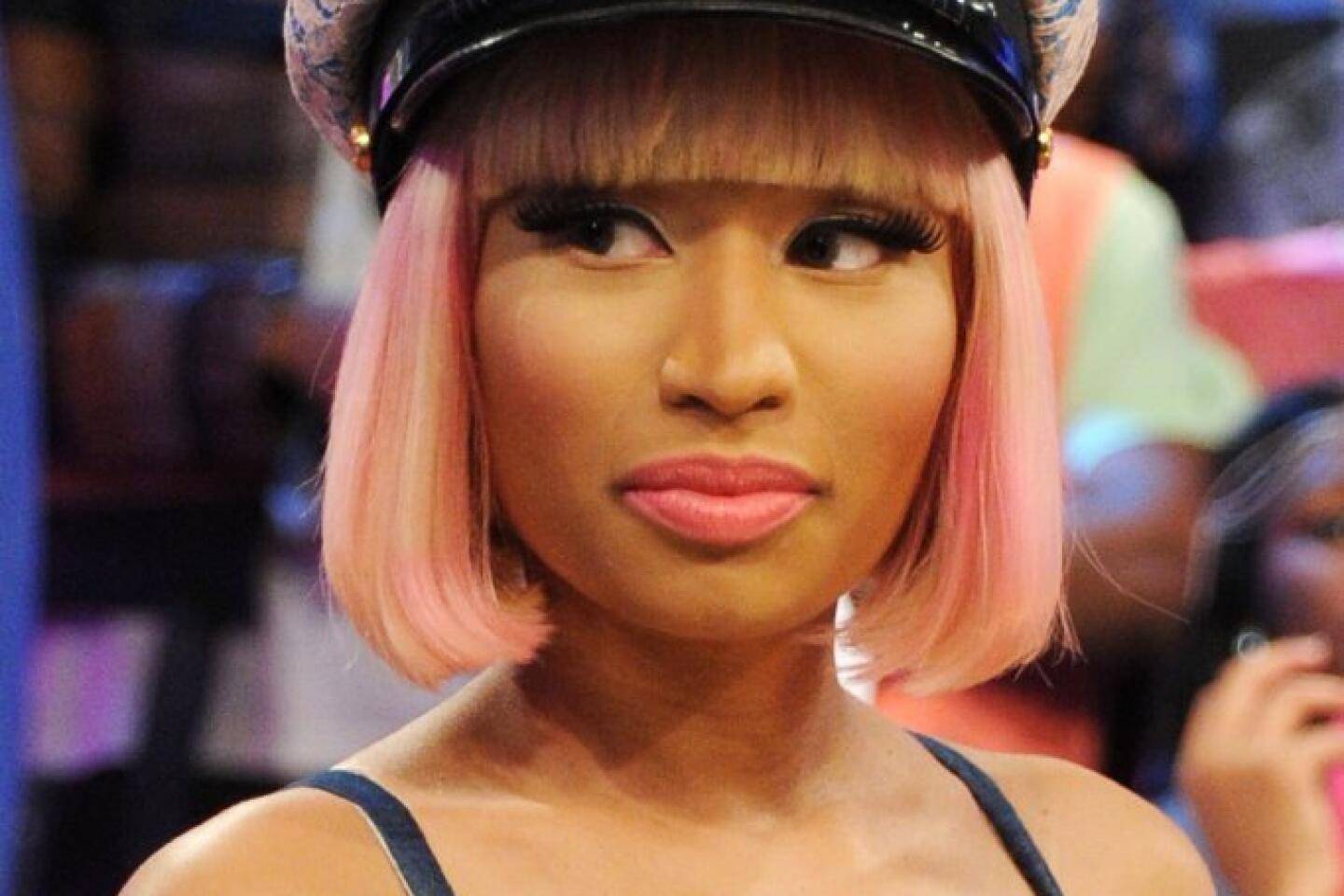

What followed was a rush of format tweaks and musical chairs at the judges’ table — Steven Tyler, Mariah Carey, Jennifer Lopez, Nicki Minaj, Keith Urban, Harry Connick Jr., etc. — that left fans unsure what to expect. Recent winners such as Candice Glover and Caleb Johnson have sold just a fraction of the music moved by early “Idol” superstars.

“Like everything else in pop culture,” McCall noted, “momentum is hard to maintain.”

As “Idol” gets ready to crown its very last winner, experts say a similar culture-unifying show could come again, but it’s not likely to be any time soon. But then it was never likely that a British talent show presided over by a curt record executive would become the biggest American TV smash in decades.

“I do think a phenomenon like ‘Idol’ could happen again,” McCall said, “but it will take some real visionary in the industry to find a way to connect with real Americans.”

Twitter: @scottcollinsLAT

MORE:

‘American Idol’: Why Fox is axing the show after 15 seasons

Our first review of ‘American Idol’: This show could use a gong for everyone

Complete coverage of the final season of ‘American Idol’

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.