Mark Ruffalo was schooled by ‘Normal Heart’s’ pioneering gay playwright

Mark Ruffalo, knowing his host liked sweets, showed up at playwright Larry Kramer’s Manhattan home with pastries in tow — unaware that the then-77-year-old’s health now restricted such pleasures.

It was spring of last year and the actor was set to begin production on the long-attempted film adaptation of Kramer’s groundbreaking 1985 AIDS-political play, “The Normal Heart.” Little did he know it, but Ruffalo’s true audition was just beginning.

“Are you queer?” the playwright asked right off.

“No, I’m not queer.”

“Have you read my book [“Faggots”]?’

“No.”

“Well, you have to read it, otherwise you can’t fully play this part.”

Ruffalo, recounting the exchange recently during a spirited conversation at a Hollywood hotel, called it his moment of recognition. “He was testing me,” the 46-year-old actor said with the sort of sheepish smile that hindsight affords. “And I remember just feeling a sense of fear in that moment.”

The actor, who has played roles ranging from a brawny green superhero (the Hulk in “The Avengers”) to a hapless sperm donor to a lesbian couple (“The Kids Are All Right”) in the course of his 25-year-career, now takes on Kramer’s quasi-autobiographical Ned Weeks, the ornery gay activist at the center of “The Normal Heart” who fervently tries to shake the public to action after a mysterious disease begins plaguing the gay community in the early ‘80s. Even his friends at times find him beyond obnoxious.

After enduring a winding road from stage to screen, the story, which was significantly reworked, ultimately came to be marshaled and directed by Ryan Murphy and landed at HBO. It premieres May 25.

Imbued with passion, pain and fury, the drama beckons one to look back just as gay rights are undergoing a sea change. To remember — for some, imagine — a society before gay TV characters were a commonality and same-sex marriage an actuality in more and more places.

The action in “The Normal Heart” takes place between 1981 and 1984 in New York City, when the gay community was still in the reverberations of the Stonewall riots and the sexual revolution. It hones in on sexual politics during the early days of the AIDS crisis — with its central character undergoing moments of rage and powerlessness in the fight to raise awareness while most of his co-workers counseled a more moderate, step-by-step approach.

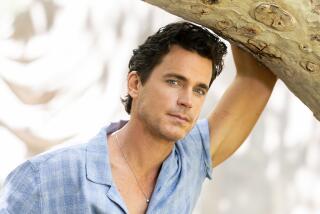

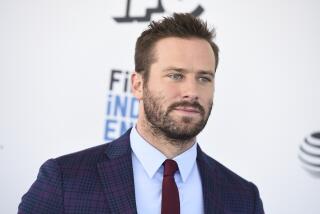

The film, which also stars Julia Roberts, Matt Bomer and Taylor Kitsch, comes on the heels of last year’s critically acclaimed “Dallas Buyers Club” and the 2012 documentary “How to Survive a Plague,” both of which tackled the early years of the AIDS crisis. That it finally has an air date is its own victory.

“It was one of those projects that was almost mythical in its inability to get made over the course of 30 years,” Murphy said. Film adaptations have been “in the works” for years — most notably, Barbra Streisand, who owned the rights for 10 years, was going to helm it. The delay hasn’t softened its significance, Murphy said.

“Prejudice killed millions and millions of people during that time,” Murphy, the openly gay TV producer behind TV’s “Glee” and “American Horror Story, said by phone. “That prejudice still exists today on some level. In hindsight, the thing that’s different, at least for me, is when I was growing up, it felt very much like my life. And now it feels like my history. I can have the happy ending — the right to marry, the right to have a child. I owe a lot of my life and freedom to those who fought the fight back then. We all do.”

‘The inhumane response’

It’s a period Ruffalo had lived through on the opposite coast, in Los Angeles, reading about the unexplained virus in the pages of the LA Weekly as a teenager. “It felt like a pandemic. And I was young, so I was still idealistic, and it was jarring to see the inhumane response to it all,” he recalled. “It didn’t compute. But Larry was right, I didn’t fully understand how deep it went.”

That’s not to say Ruffalo is unfamiliar with unbridled zeal for a cause. Today a resident of upstate New York, the actor has cultivated a profile as an outspoken anti-fracking advocate — hosting rallies and speaking out on various cable news programs. “I knew what activism looked like inside and out,” he said, pointing to the ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) movement, a grassroots AIDS initiative co-founded by Kramer, as a model.

The pair’s initial sit-down lasted three hours. From there, a friendship started. And the tutelage followed. The legendary — and divisive — figure in the gay rights movement offered a master class of sorts, sharing photos and stories of the places and people at the heart of the turmoil. He even offered Ruffalo his round-framed glasses for use in the film.

Kramer, who is HIV-positive and has undergone health complications since receiving a liver transplant more than a decade ago, retains his sense of humor. In an email, Kramer said he was struck with disbelief when Murphy put Ruffalo’s name forward for the role of Ned.

“To be played by such a fine and handsome actor (I should have looked this good.)” he wrote. “We hung out together a lot, and I didn’t ask myself, can he play me. Actors are hired to portray, and good ones like Mark make it their job to go for it all out, which Mark did. He was also extremely passionate about his taking on the part, consumed with it. And this was very touching to me.”

Ruffalo, as instructed, would read “Faggots,” a pre-AIDS, ‘70s-set novel that explored sexual excess on New York’s Fire Island. Ruffalo dubs it one of the “great American novels. It’s as well written as Fyodor Dostoevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment.’ I really started to understand where the gay culture was before, where it was after, how prophetic Larry was. He was already saying, ‘We are not the sex that we’re having!’”

It’s a topic that incited the soft-spoken, genial actor at various intervals during the interview — to the point where his twitchy movements resulted in some spilled green tea. “This movie is less about AIDS than it is about love,” he said. “That’s what blasts through! That’s what carries them! That’s what saved them! It’s the grace. It’s so powerful. ... Ugh. It’s so moving. Love in every sense of the word, every permutation.”

Ruffalo puts that vehemence into the role of Ned — at times practically slapping viewers to take notice — as his friends, particularly his first true love, Felix (Bomer), become stricken with the disease. The moments of heartbreak are equally striking, Murphy said. One scene finds Ned in a heated argument with Felix that culminates with the revelation that Felix has contracted the disease.

“The small minutiae of emotion in that one scene is just extraordinary,” Murphy said. “There is like a 10-second fury where he’s quiet and taking it in to full-on rage. Listen, Mark and I would talk each day about how terrified we were being responsible for this piece. It was rough. But you really see Larry in him. He did an imitation of Larry that was not really mimicry but deep from the soul. And Ned is Larry.”

One might never know Ruffalo (who can next be seen opposite Keira Knightley in this summer’s romantic drama “Begin Again”) had trepidations about taking on the role. The actor, who had been tied to the project during Streisand’s failed attempt to get the film made, voiced his concerns with Murphy.

“I sort of felt like we were in a place where the character should and could be played by a gay actor,” Ruffalo said. “I think I was just insecure. This is big material. And it’s Larry Kramer. I’m not as smart as Larry Kramer. I’m not as strategically minded. I’m struggling against my own limitations. And I mean, I have passion, but that guy would take that to the death if he had to.”

Murphy and Ruffalo stressed that the film takes on a new focus from Kramer’s agitprop drama. Murphy, who bought the rights to the play in 2012 and spent three years working on the script with Kramer, estimates that almost half of the film is new material — for starters, it opens and ends in scenes not witnessed in the play.

“The play was meant to get you out of your seat, to take you out of your ennui and drive you to action,” Ruffalo said. “But a lot of time has passed, so it becomes something else. We don’t have to shake the audience out of apathy. What we do is deepen the picture, show what kind of journey we were on that led us to where we now find ourselves.”

Now many ought to be ready to remember this story, he maintained.

“There was a gift in what happened with AIDS,” Ruffalo said. “The gift was that the gay community realized they were human, and that they demanded to be treated as so. It’s a story that has to be told and remembered. Every oppressed group has to carry its past into the present so that it becomes a bulwark against moving backward. The fight isn’t over.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.