Why Luke Perry’s death is so personal for many forgotten Gen Xers

My phone buzzed at 5:07 a.m. Monday morning with a text from a friend who was in India with his wife and son. The text read: “As Luke Perry goes, so does the world.”

I was too groggy from the sleeping pill I’d taken to respond, but I remember registering awareness that Luke Perry was sick. Then again, I could have been dreaming. It wouldn’t have been the first time Perry had visited me in my sleep.

In fact, there was a period when my life amounted to little more than brief and fraught interruptions between episodes of “Beverly Hills, 90210.” It was circa 1997-98 and the FX Network was playing four repeats a day of “90210” in sequence — at 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. and then at 4 p.m. and 5 p.m. On Wednesdays, when new episodes aired on Fox, I’d consume five hours of the show. Between episodes, I’d do the things I needed to do to stay alive — get coffee, take a walk, try to earn a buck as a writer — but watching “Beverly Hills, 90210” was what gave structure and purpose to my days.

I watched the show so much that when I tried to sleep, the theme song — a weirdly anthemic mash of hair-band, whammy-bar guitar and Kenny G saxophone — would ring in my head. When I did sleep, it was often merely a portal into the lives and dramas of Dylan McKay (Perry), Brandon and Brenda Walsh (Jason Priestley, Shannen Doherty), Kelly Taylor (Jennie Garth) and the rest of the gang. Even my dreams were episodes of “Beverly Hills, 90210.” At that rate of immersion, the lines quickly blurred between where the show ended and I began.

I was in my early 30s at the time, newly sober and living in a threadbare Hollywood apartment with a mattress on the floor and a cardboard box draped with a bandanna over it for a table. Like a lot of fools, I’d been propelled to this juncture by inchoate yearning. Maybe for some sunshine, maybe for a swim in the ocean, maybe for the fantasy of having grown up surfing Point Dume, driving a vintage Porsche and dating Kelly Taylor.

ALSO: Luke Perry of ‘Beverly Hills, 90210’ and ‘Riverdale’ fame dies at 52 after stroke »

ALSO: Why my Luke Perry was ‘90210’s’ Dylan McKay »

When I finally arrived in L.A., from a rented house in the Pittsburgh suburb where my family had landed after moving nine times by the time I was 10 — cities, states, countries — I’d moved 19 times in 32 years. By yearning, I think I really mean wanting a home.

Depression is a vortex and a vacuum. It sucks us in and we fill it up with obsessions. Sometimes our obsessions become our lifelines. Fred Exley had Frank Gifford and the New York Giants through which to live vicariously as an all-American football hero when he wrote “A Fan’s Notes.” I had Dylan McKay and the Peach Pit, which suspended me in an amniotic California dream.

A little before 7 a.m., and still not fully aware of the gravity of Perry’s situation, I responded to my friend in India: “Right?”

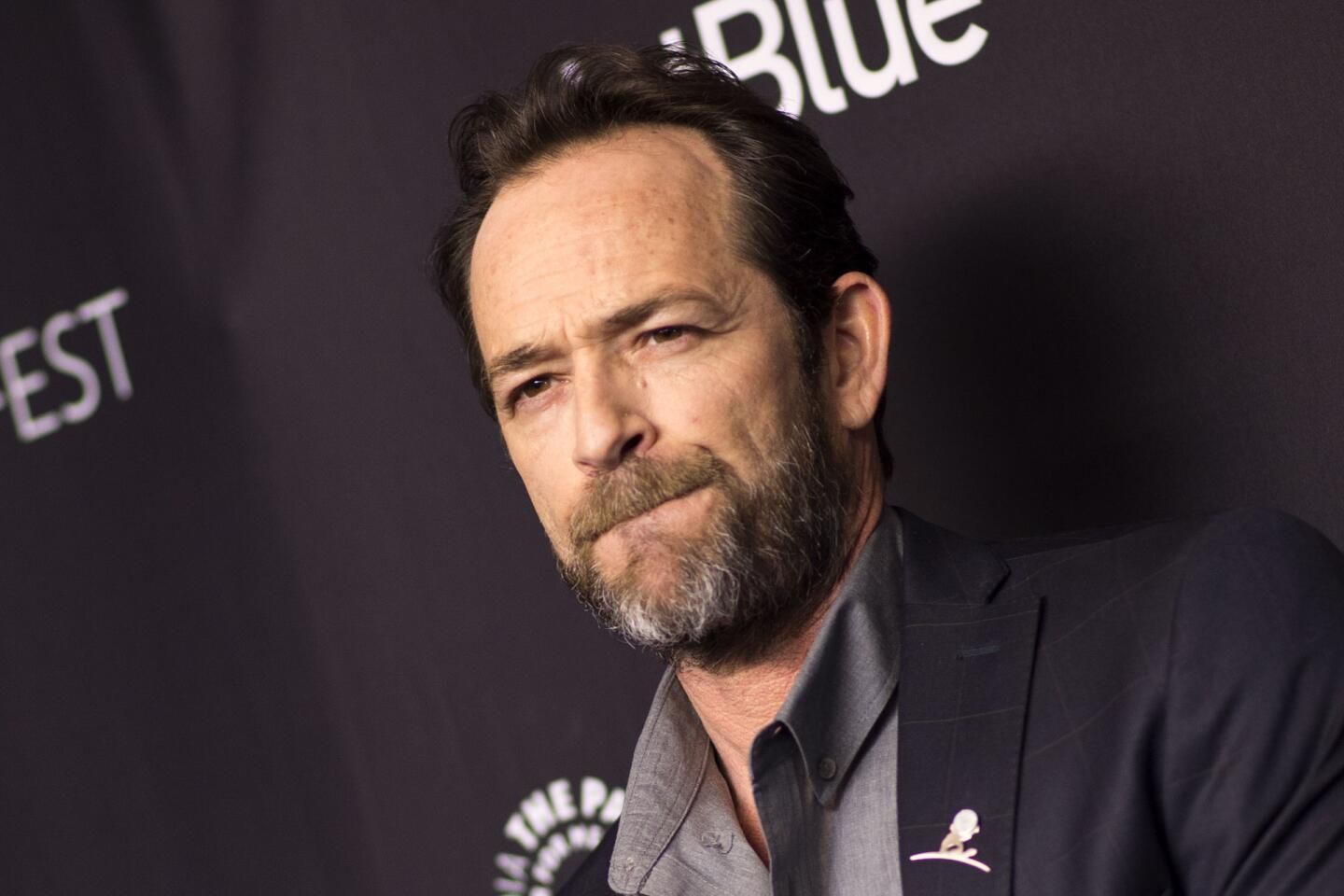

We were speaking in code at this point, signifying that we’d agreed we weren’t ready to surrender Luke Perry to the final outcome yet. His fate might not have mattered as much 10, even five, years ago when mortality for our generation, Generation X, was more abstract. But the death of singer Chris Cornell a couple of years ago seemed to signal a change. A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report shows mortality rates for Gen X are on the rise, fueled by suicide, alcohol-related diseases and economic downturns.

If that wasn’t bad enough, Gen X was nowhere to be seen when CBS recently posted a list of generations — from the silent (1928 to 1945) to the post-millennial (1997 to now), wiping us out completely. Squeezed by a media fixated on boomers and millennials, maybe we really are the Lost Generation — and maybe rallying around Perry is a way of being heard. Then again, most of my cohorts reacted on social media to the CBS snub in typical Gen X fashion: “Whatever, never mind.”

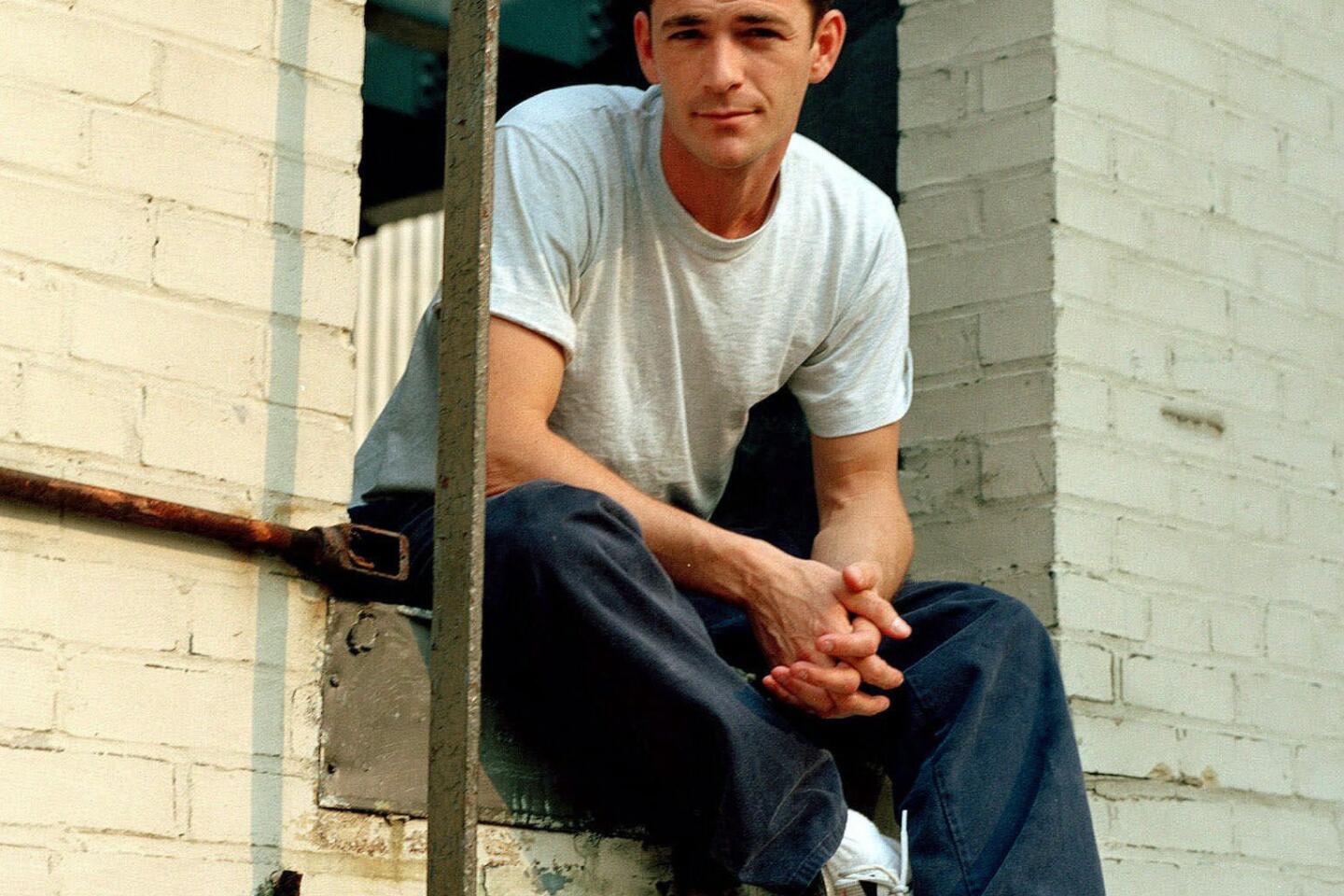

It’s hard, though, to overstate what a sensation Luke Perry was back in the day. He was beautiful enough to cause commotions in tabloids and in teenagers’ chests, but there was always more to Perry than a pinup. He seemed strong and decent. His eyes were full of mischief and kindness, and he said a lot with a little. In an era that’s bestowed tech disrupters, investment bros and chattering-class screamers with some sort of exalted holy status, Perry had the whiff of a more sacred American archetype about him. Maybe we were just proud of him.

ALSO: Luke Perry’s death upends ‘Riverdale’ »

When I posted something about Perry’s death on social media and mentioned how surprisingly deeply he’d gotten under my skin, I half expected to be made fun of. This was, after all, Dylan from “Beverly Hills, 90201.”

Instead, the thread filled with similar sentiments. One friend wrote about how Perry had offered to help her pick up dog poop on Park Avenue when she was struggling to handle two Great Danes. A writer friend who interviewed him a few years back shared that she had saved a sweet voicemail on her phone for a long time: “Hey, Em, it’s Luke Perry.” A third friend said he was kind to a childhood friend of hers, who was just another Hollywood studio minion at the time. “Let’s just say he didn’t treat her like a minion,” she wrote. “He knew her name and would pop in and say hello.”

And even though “90210” could hardly be called prestige television, the show was good. Maybe not five-times-a-day good, but it didn’t last 10 years because it sucked. Something about it salved my wounds from decades of dislocation, of always having one foot out the door, of being embarrassed by my sublimated vulnerability and desire to connect, of struggling with the harsh light of sobriety. Or, maybe they were old wounds from high school, where my resume tells one story and my graduation pictures tell a different one about a kid with hair that never conceived of Dylan McKay’s daring James Dean’s pompadour, whose right eye had a patch over it to conceal that it was green, black and swollen shut and whose hand was in a cast — a pirate costume on someone who was desperate to be normal.

Dylan wouldn’t have tried so hard. He had his own code and he rarely got ruffled. Even on TV he was more authentic than me.

Sure, the Peach Pit crew had their struggles. They fractured and wounded each other, but they helped each other heal too. They knew one another’s scars. I was surprised to find myself in my early 30s longing for that intimacy.

Often aloof and mercurial, Dylan nonetheless was the gravitational force in their universe, almost like a father. He took in the rubes from the Midwest and sheltered them with his cool. His affirmation enabled gawky David Silver to come into his own and annoying Steve Sanders to find some grace. Dylan was respectful to women.

I’m not ashamed to say that in the early 1990s when I was in my late 20s, I grew out my sideburns and tried to do something with my hair. I remember walking down a street in San Francisco one night with a couple of female friends. We were, or at least I was, inebriated. Three men passed us on the sidewalk, one of them muttering something incredibly rude at one of the girls under his breath. I stopped and asked him, ”What the … did you just say?”

He taunted back, “Oh, who are you supposed to be, Dylan McKay?”

I took off my prized, brown leather jacket, tossed it to one of my friends and calmly walked back toward them, my intentions clear. “Yep,” I said.

Under Dylan’s dominion, the Peach Pit crew became worth spending time with — a lot of time, in my case. We heal in our sleep, and I don’t sleep much or very well. I think what I was actually doing with all the “90210” viewing was surrogate sleeping. I was trying to heal.

Perry left the show in 1995, seeking more significant roles. Things didn’t quite pan out, and he returned in 1998, just as the funk I’d been in started to lift. I didn’t tune in as much after that, but I remained thankful for all that Perry had given me when I needed him. I agreed he deserved better material; we both did at that point. I tried to do something about it when I found myself driving to Texas with Wes Anderson on the eve of “Rushmore’s” release. We were somewhere in Arizona, I think, when I suggested an inspired casting-against-type of the sort that would garner rave revues and launch a sublime second act à la Bill Murray.

“How can you miscast him?” Anderson asked me.

“I suppose as a bus conductor or an airplane pilot.”

“He’d just become that,” Anderson replied. “He’s such a chameleon.”

Anderson was probably half a decade too young to get it. But Quentin Tarantino, born a few months after me, understood. Perry’s final film appearance will be alongside Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt in “Once Upon a Time In Hollywood.”

At 10:21 a.m. my friend texts me again: “Dead … wow.”

I come clean with him about my decades-old “Beverly Hills, 90210” obsession. He hit me right back. “He was underrated. I mean that.”

All that time and I wasn’t really alone.

ALSO: Luke Perry remembered: ‘a character actor in the body of a heartthrob’ »

The cast of “Riverdale” talk about the new look for the “Archie.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.