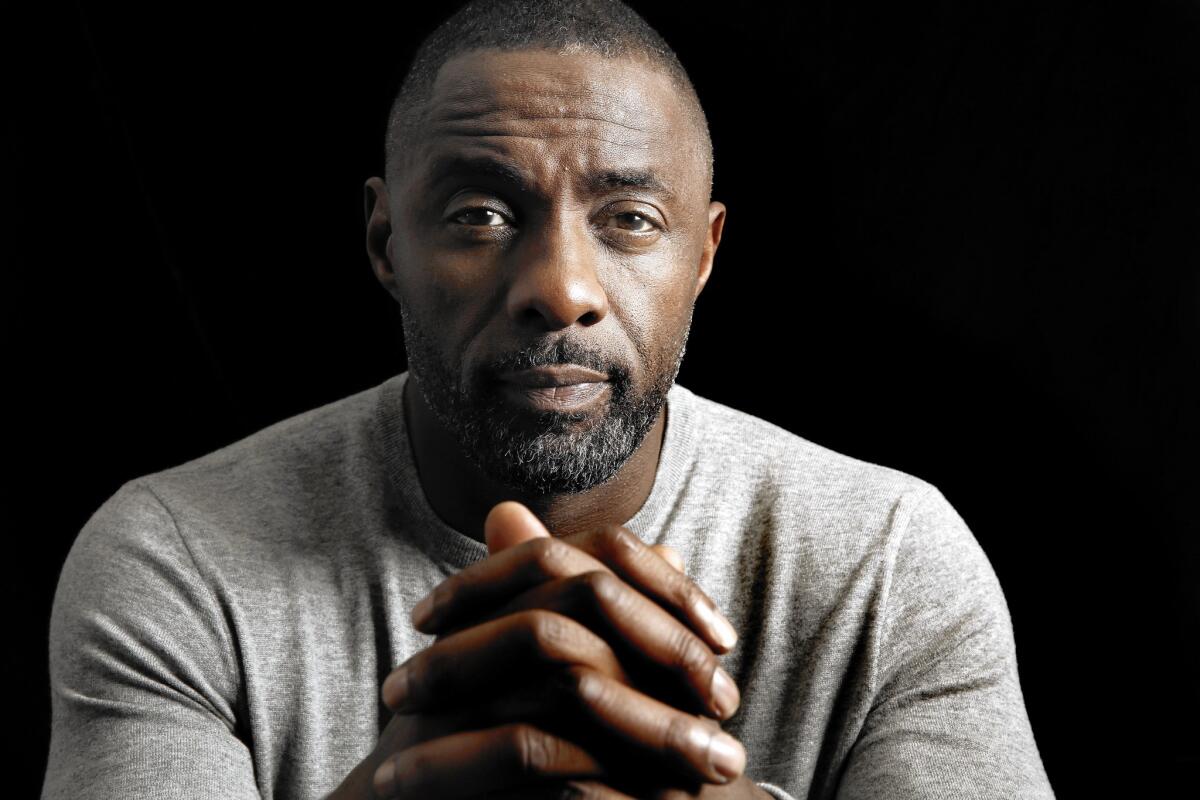

Q&A: Idris Elba reflects on playing a TV detective in ‘Luther’ and a commander of child soldiers in ‘Beasts’

Reporting from NEW YORK — Even if Idris Elba is sick of talking about it — and, for the record, he is — it’s easy to understand why the Internet has already cast the British actor as the next James Bond. With charm to spare, an undiluted masculinity and the kind of good looks that can reduce even the most sensible women to blushing teenagers, the 43-year-old is a rare commodity in Hollywood these days.

But the truth is that Elba already has what he considers his franchise. The actor, who first registered with American audiences as Baltimore drug kingpin Stringer Bell in David Simon’s acclaimed HBO series “The Wire,” has gained an international following as anguished London detective John Luther in the pulpy TV drama “Luther” from creator Neil Cross.

Luther was last seen throwing his signature tweed overcoat into the Thames and apparently riding off into the sunset with Alice Morgan, the charismatic psychopath played by Ruth Wilson. After a two-year hiatus, the series returns for a one-night special Thursday, providing fans with long-awaited updates on Luther, his love life and, perhaps most important, his outerwear.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

It’s a busy time for Elba, who is currently juggling two Golden Globe nominations — one for “Luther” and another for his chilling portrayal of a West African warlord in Cary Fukunaga’s child-soldier drama, “Beasts of No Nation.” A music producer, DJ and rapper, Elba also released a “Luther” concept album this week called “Murdah Loves John” and opened for Madonna on her Rebel Heart tour last month.

A jet-lagged Elba, clad in the off-duty actor uniform of knit beanie and fitted gray thermal, recently found the time to discuss his return to “Luther,” the message that attracted him to “Beasts of No Nation” and the creative restlessness that keeps him so busy.

You’re a movie star with Oscar buzz. What brought you back to “Luther”?

Going back to “Luther” actually feels like a good step forward for me. It’s such a great character, one that I feel is still in its infantile state. It’s different from the films “Beasts of No Nation,” “Star Trek” and the lot. This is a character that I’ve got a built-in audience for, they expect something from me, and it feels quite nice to be able to deliver that. The audience is still engaged after a two-year break.

The show has had an interesting trajectory — people are still discovering it.

For sure. That seems to be happening more and more. It gets a worldwide audience, but slower. The good ones tend to really take their time to really penetrate, as with “The Wire,” as with “Luther.”

Troubled detectives are pretty common on television. What do you think it is that makes Luther different from all those others?

In this day and age, we talk about escapism and all of that, right? On the news every day it’s a bit like an episode of some drama or something. What you don’t see is that one guy, that one woman, that one hero, that’s going, “Right! I’m going to go sort this out! I’m not bound by politics, or being politically correct, I’m going to go get this bad guy!” It is pure escapism, it’s unapologetic.

He’s very un-English ... he’s very much American like: “[expletive] you, come on!” [throws a few punches]. That’s very un-English. [in posh accent] “Shocking! Can’t be doing that.” Point is that audiences want to see someone ... go for it unapologetically. … We live via him. We get a real satisfaction through him. I think what Neil Cross designed is a graphic novel. It’s novelistic, it’s big and gruesome.

Let’s talk about Alice Morgan. What do you make of their relationship?

Someone like Luther absorbs so much, has to deal with so much, to have somebody share his intellect, take on his intellect and carry it for him, is such a liberating thing, albeit someone who’s on the other side of the law. I think he finds real connection in that. I don’t know if it’s romantic, though.

She gets to do what he can’t.

That’s right.

Is there more Luther in you after this?

I hope so. I really want to explore it further. I think there’s films, I even envisage a play. I’d love to go back to theater.

You continue to work as a DJ and record producer. Is there something about music that creatively satisfies you in a way that, say, acting doesn’t?

Yes, I can be honest. You can ask me something about my kids now, and I’ll be like, “Uhhh …” But in a song I’ll totally talk to you about it. It’s an offering from me as opposed to being withdrawn from me.

You’ve also branched out into directing, with a music video for “Mumford and Sons,” and writing. Is it safe to say that you’re a creatively restless person?

Definitely. Actors by nature, anyone that’s got real talent, is basically a sponge. I’ve absorbed a lot. I’ve got to have some sort of release for that information and stuff that I’ve learned. I think some actors just want to do that and channel it back into acting, but for me I need to get rid of it. It’ll end up making records, directing or writing.

You have said that in contrast to the complicated characters you play, in real life you are a simpleton. Surely you can’t really mean that?

I’m not tortured, but I’m not the life of the party either. If I’m not working and I go somewhere, to someone’s house for dinner, I’m very much trying to blend in. I don’t have anything extra to contribute more than the next guy in terms of personality. If I go into a room, I’m not like “Hey! I just got back from Dubai!” It’s just not part of my fabric. Somehow, on film, I can be as complex as you like. There’s nothing really fancy about me, it’s just that I’m a good actor.

Let’s talk about “Beasts of No Nation.” It’s a brutal watch.

Do you have a family? Having a family, it touches us.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Your son was a newborn when you made the film. I’d imagine that would make it especially difficult.

Totally. I’m not tortured, but that’s tough. To leave any newborn baby, and then go off and be someone that kidnaps children, is just lik, “OK, it’s time to play acting.” It’s a [expletive] mind [expletive], because I’m not home to protect my own. There’s all this odd stuff that cooks under the surface. Ultimately, I wanted to make that film pop. It was a tough sacrifice, but I needed to do it. The film is important. My son will see it one day and appreciate it.

So the message was an important selling point?

Soldiers that were children 10 years ago, they’re only 20 now. The effects still permeate our world. Syria is a massive example of people recruiting young kids to fight for things they don’t really understand. This film is a beacon to highlight that. At 10 years old, if I heard anything about planes coming out of the sky, people going to Paris and wearing bombs, I’d be like “This is a terrifying world!” But then, if someone convinced me that “Yo, you got to fight for something,” I could be easily swayed, surely. We do have to pay attention to the kids: What are we feeding them? When we’re all dead and gone, what’s their life going to be like? Any sort of message that can do that, in my medium, why not?

How did you find the humanity in your character, the Commandant?

Weirdly enough, my parents come from Sierra Leone, the men in my family have that texture — that sort of cajoling, [in West African accent] “Who’s the big man round here? Hey, is it you?” that sort of thing. None of the people in my family had anything to do with anything like [what happens in the film], but that texture, that warmth is what I tried to capture. I had to make him relatable to what I know.

There were former child soldiers from Liberia who worked on the film. Did you get the sense they had been able to find any kind of peace?

You hope so, yes. When you look someone in the eye and they say, “Man, when I was that age I must have killed 40 people,” you can sense that no matter what happens they will always have that memory — stuff that we would never even understand is always sitting at the back of their minds. I remember seeing a guy [on set] who lost his temper completely over something really small. There’s hope, but they’re scarred.

There’s a lot of Oscar talk around your performance. Are you wary at all about that?

I have kept it at a distance, especially for this character. This character for me is not a guy I’m celebrating. We made a great film and a poignant one, but I just don’t feel comfortable standing up there going, “Hey look at me! Wasn’t I a great child molester? What do you think? Wasn’t it amazing?” I’m just not doing that.

You haven’t really played many romantic leads, I’ve noticed. Why is that?

I don’t know if I come across as romantic.

Really? I think a lot of people would disagree with that.

I do tough roles, guys who are complex. A guy who’s a little bit fumbly and falls in love — I don’t think anyone’s got the imagination to write a role for me like that yet.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.