Bill Hader breaks out of the ‘SNL’ mold with HBO’s ‘Barry,’ the story of a hit man with a dream

Inside a dark soundstage in Culver City last year, Bill Hader stands at the corner of a stage. Dressed to the nondescript nines in a chambray shirt and khakis, he looks nervous, glancing at pages held tightly in his hands as his fellow actors debate a character’s morality in a rehearsal for “Macbeth.”

He’s reticent but finally interjects in the familiar, Midwestern half-drawl he deployed for eight seasons on “Saturday Night Live. “I don’t know, I think Shakespeare whiffed it.” With increased aggravation he builds a case from his own background that there’s a possibility for redemption.

It’s a strange conclusion, but in the context of HBO’s “Barry” — a half-hour series debuting Sunday featuring Hader as co-creator, star and, for the first time, director — it follows its own sort of logic.

“Barry” is the story of a depressed, disconnected ex-Marine turned hit man (Hader) who, while on assignment in Los Angeles, winds up in an acting class, one of those blackened incubators of dreams and delusions aimed at those looking to break into the business. To his surprise, Barry catches the acting bug and must reconcile the undercover life of an assassin with a job that needs a spotlight.

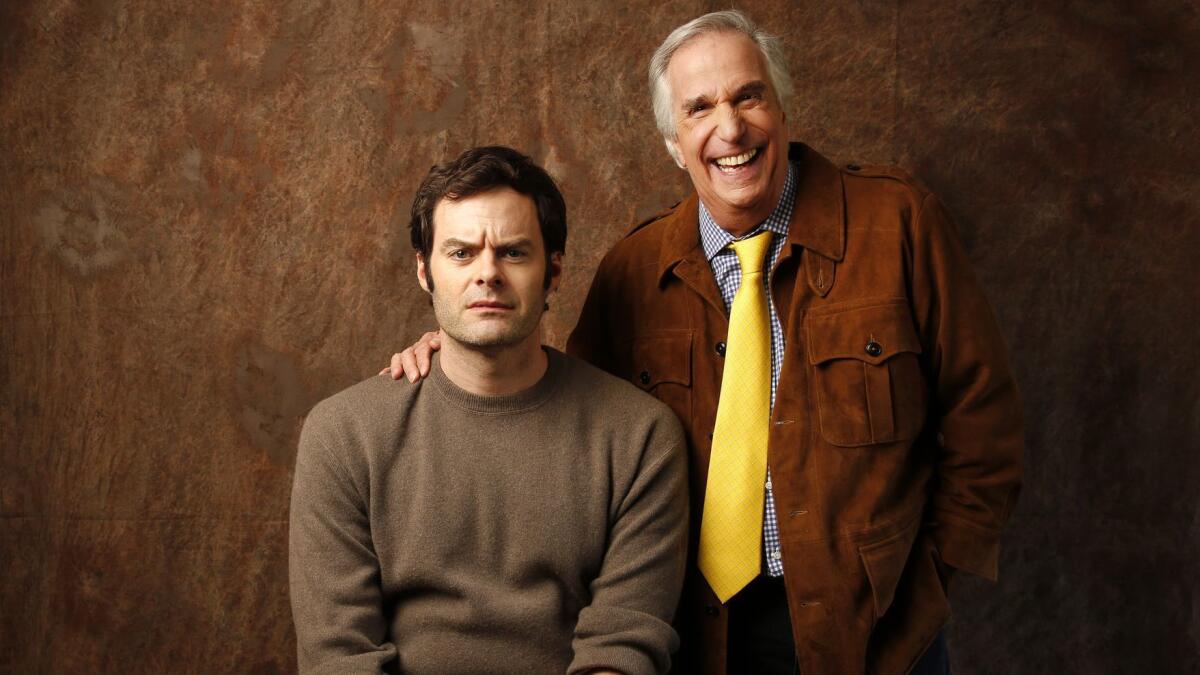

Hader confers around a monitor with series co-creator Alec Berg (HBO’s “Silicon Valley”) to check whether his semi-confession at the rehearsal is working. Back in the theater, his on-screen classmates and acting teacher (Henry Winkler) continue riffing some responses. “My tummy enters the room before I do,” Winkler jokes with one of them between takes.

Although the various struggles surrounding the acting classes held in various small theaters around L.A. was a new experience for Hader, who was briefly part of L.A.’s Groundlings before “SNL,” he was also on familiar ground.

“It’s this funny thing where everyone is very bonded together, but they’re also competitive,” Hader later says, slumped in a folding chair between takes. “That was ‘Saturday Night Live,’ you know? So it was very much my experiences of some of the dynamics — not specific people or anything, but that feeling.

“I remember when we were writing this season of [‘Barry’] thinking, ‘Oh, well, it’s kind of like when I joined ‘SNL’ and being a little bit of an outsider: How do I get in? How do I figure this thing out?’”

As anyone who saw him during that run, Hader indeed figured the show out. But behind the scenes, he was no more comfortable than Barry. “The live thing was hard for me,” Hader told the audience at the Television Critics Assn. panel for the show in January. “That red light would go on the camera, and all of a sudden all of my friends in Oklahoma were watching me.”

“He basically spent eight years terrified,” says Berg in a later phone call. “But he was so good at it, he kind of just kept at it. I thought the idea of somebody who was a prisoner of their own gift was a very interesting area. How much do you owe to that gift, and how much do you have to service that gift in spite of your desire to run away?”

As the idea coalesced, Berg says he was a little reluctant to add to pop culture’s long line of hit men: “It’s like the dog catcher in the old ‘Dennis the Menace’ cartoons — there is no dog catcher, it’s not a thing.”

But the conflicting nature of Barry’s day job and passion became more appealing. “It started to become an interesting dynamic of a guy who hates what he does, and falls in love with something that he’s terrible at,” Berg says. “And it started to become interesting when it was like, oh, if he tries to become an actor, that can get him killed.”

Given the show’s particulars, absurd comedy was practically inevitable, and “Barry” is a funny show. But it balances those moments with a story that’s often far more dark and human than expected.

“Watching certain hit man movies, we really wanted to make sure it didn’t feel like that, and that the violence in it was never really funny,” Hader says. “It’s a world [Barry] wants to get out of, so you kind of want to play it for what it is, which is pretty ugly.”

The same can be said for the world of acting. Midway through the season, one of Barry’s classmates (Sarah Goldberg) is confronted with a “casting couch” moment with a prospective agent, and her raw, shellshocked response is harrowing to watch, especially given the many reports that spurred the recent “Time’s Up” movement.

“We had heard a story about somebody who had gotten a line like that,” Berg says of the scene, which inevitably carries more weight now than when it was written.

“It just happens that things have swung around where [sexual harassment] seems a little more in the news,” he adds. “I don’t think there’s been any shortage of that for the last decade.”

Though superficially a breakout series for Hader, “Barry” is the kind of show that luxuriates in details along its periphery. Anthony Carrigan of “Gotham” is an unexpected standout as a weirdly upbeat Chechen mobster, and character actor Stephen Root — whom Hader calls “a treasure” — plays Barry’s boss with the same distinctive, unhinged drive that has marked his appearances in “Get Out” and the films of the Coen brothers.

And then there’s Winkler, who is lord of his realm when teaching but is just as much of a humbled Hollywood bit player as his students in going out on assembly-line auditions between classes.

For his part, Hader says one of his biggest challenges was keeping up with his cast as an actor, and part of that process in playing Barry was becoming adept with looking awful at it.

“It’s really hard,” he says with a grin. “Julianne Moore does it really well in ‘Boogie Nights,’ but it’s really difficult to not come off like you’re trying too hard. I love true crime shows, so in a lot of those re-creations, some of those actors are really helpful to watch. … Not knowing what to do with your hands is a big one.”

A veteran actor and producer who has also shown a deft hand with twisted comedy on “Arrested Development” and “Children’s Hospital,” Winkler also puts his own stamp on Cousineau, Barry’s acting teacher, who Berg says was initially written as an abusive instructor.

Berg remembers, “Henry is such a warm guy and there’s an innate humanity to him that he’s not a sadist, he’s not a bully. And [the character] started to become much more three-dimensional.”

“I had the most wonderful time [at his audition] because I made Bill Hader laugh,” Winkler marvels, standing outside the soundstage while peeling a tangerine. “Holy mackerel. Not an easy thing.”

In preparing for the role, Winkler admits to getting caught up in the script’s many twists, so much so that he felt he had to write Hader with a simple yet hopeful question: “Bill, do I live?”

“He emailed a reply,” Winkler remembers. “It was ‘Hahahahaha.’ ”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Follow me over here @chrisbarton.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.