‘The Mod Squad,’ ‘Adam-12’ and how TV brought the counterculture into 1968’s cop shows

“One black, one white, one blonde” was the tagline for a new kind of cop show that premiered in 1968 on the heels of Vietnam’s bloody Tet Offensive, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, a shootout between the Black Panthers and Oakland police and the passage of the Fair Housing Act.

“The Mod Squad” featured a multi-racial trio of non-conformist crime fighters: Long-haired rebel Pete. Black activist Linc. Flower girl Julie. On other long-running detective shows of the era such as “Dragnet,” they’d have been cast as the disrespectful young people arrested during aimless protests or a raid on a free-love cult.

The rabble on the wrong side of the law was now the law. Series TV, like the country, was changing. It had one foot in “The Mod Squad,” while the other remained planted in the safety and comfort of institutional protocol, meaning the crisp uniforms and above-the-ear-hairlines of another cop series that debuted that year, “Adam-12.”

The police procedural followed officers Pete Malloy and Jim Reed as they patrolled the wide-open streets of a city called Los Angeles in their black-and-white patrol unit, 1-Adam-12. They spoke in a law enforcement jargon that was largely new to audiences, and the drama was produced with a documentary-style realism that focused as much on the culture of the streets as it did on the officers and the crimes.

READ MORE: A look back at entertainment in 1968 »

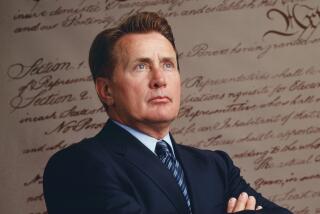

“Adam-12’s” Pete (Martin Milner) and Jim (Kent McCord) were young people who followed the older conventions. “The Mod Squad” were young nonconformists fighting against the status quo for a more just tomorrow. Together they represented a culture grappling to understand its next generation, the under-25 demographic that made up nearly 50% of the America population in 1968.

Linc (Clarence Williams III), Julie (Peggy Lipton) and Pete (Michael Cole) could do what Sgt. Joe Friday could not: infiltrate love-ins and sit-ins, protests and drug dens, rock concerts and college campuses without looking like The Man.

They were a sure sign that the countercultural movement had fully infiltrated series TV, a realm that had largely been resistant to the seismic shifts outside the network studio doors. After several years of social unrest over war and changing values, networks began taking what Americans were seeing on the news — a generational revolution of long-haired men and free-spirited women — and reworked it into scripted shows for a new decade.

The rabble on the wrong side of the law was now the law.

Network news and the fledgling news magazine “60 Minutes” (which first aired on Sept. 24, 1968) were where social unrest, war and the fallout of changing values was covered. Scripted programming across the three big networks was where Americans went to escape the confusion. Popular ongoing series such as “Gunsmoke,” “I Dream of Jeannie” and “Bewitched” portrayed worlds far from the real one.

The gunslingers of Dodge City knew nothing of communism and the Viet Cong, the 2,000-year-old genie and her astronaut master weren’t exactly arguing civil rights around the dinner table, and that pretty witch who was trying to pass as a normal suburban housewife? She was no Gloria Steinem. In fact, Samantha, like Jeannie, was forbidden from using her formidable powers by the man of the house. At least feminists had Endora (Agnes Moorehead) to roll her eyes at son-in-law Darrin and wave her wand at such 1950s-style misogyny.

A few years later, Rhoda and Maude definitely took after Darrin’s self-determined mother-in-law, not his subservient wife.

It would be great to say that producers and directors took the reins and demanded that at least some of the shows they made actually reflected the times; it’s more likely that sponsors realized they needed inroads to a new, huge, untapped demographic — an American consumer out there just waiting to buy the world a Coke and keep it company.

And so those long-haired men, free-spirited women and previously invisible African American characters began popping up in the scripted shows of 1968, including “Julia,” the first sitcom starring a black woman, Diahann Carroll, as the lead.

READ MORE: Watching ‘The Smothers Brothers,’ ‘Laugh-In’ and the Democratic National Convention »

They were far from perfect, but they set the stage for an explosion of programming in the 1970s that satirized politics, gender roles, race and class in shows such as “The Jeffersons,” “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and “All in the Family.”

The network co-opting of hippie culture that happened in fits and spurts was often comical, and rarely substantial. Look no further than “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In,” “The Monkees” and “The Banana Splits” for proof that style trumped message. Goldie Hawn and Davy Jones were not railing against materialism or Vietnam or an older generation that’d thoroughly blown it, but boy, were they having fun with free love, fringe and flower-power imagery.

Established shows that had some autonomy due to their popularity did take risks. “Star Trek’s” Capt. Kirk (William Shatner) and Lt. Uhura (Nichelle Nichols) shared what most consider American television’s first interracial kiss in 1968. “Where I come from, size, shape or color makes no difference,” said the captain of the starship Enterprise, describing an America that we’re still struggling to achieve.

Kids’ Saturday morning shows introduced the wild-haired, headband-wearing rock band the Banana Splits, actors in animal suits who fashioned their antics after those of the Monkees, who fashioned their antics after those of the Beatles in “A Hard Day’s Night.” A knockoff of a knockoff that sold a lot of Cap’n Crunch. PBS also introduced the congenial “Mister Rogers,” who lived in a neighborhood where cardigan sweaters and loafers were the wardrobe of choice, and pop culture embraced it all.

The wacky variety show “Laugh-In,” which premiered as a special in 1967, had presidential hopeful Richard Nixon on in ’68, where he uttered the show’s cool catch-phrase “Sock it to me.” Nixon later joked that his appearance on the show was largely why he won the election.

“Laugh-In” invited Sammy Davis Jr. on the show as a frequent guest performer, but television was still largely a white affair.

When “The Mod Squad” arrived, producers Aaron Spelling and Danny Thomas chose a stoic black undercover crime fighter, whose back story included being arrested during the Watts riots in 1965, for a lead character. Linc’s history hinted at anger toward a racist system, which made him a new sort of black character on series TV — one who wasn’t entirely whitewashed.

He had an afro and often wore big mirrored sunglasses. It was a look frequently used to portray the black hoodlum in other shows, but now a brother was the righteous avenger fighting bad, clean-cut, white guys. It was a role Bill Cosby had cut the path for earlier in the decade with “I Spy,” with his character of an intelligence agent.

Stereotypes weren’t shattered with either show, but they were certainly challenged. And so was the idea of what would sell on the small screen. When “The Bill Cosby Show” premiered in 1969, it marked the first time a black actor starred in an eponymous sitcom. From there, it was “Good Times,” “Sanford and Son,” “What’s Happening!!” and “The Jeffersons,” a slow march toward representation that’s still in progress.

“Adam-12” contributed another sort of realism to the end of a decade that saw all too much of it. The show patrolled the real streets of L.A. and based some of its stories on real cases, which meant it wasn’t always the people who represented the establishment — older white folks — who were on the right side of the law. The cops of “Adam-12” represented a new breed of officers who seemed to understand the shifting world around them.

They were, oddly, in step with their hipper brethren of “Mod Squad.”

“The times are changing,” said the veteran, square character, Capt. Greer, in an episode of “The Mod Squad.” “They can get into places we can’t.” And they did.

MORE ON 1968

Days of rage and wonder: Full coverage of 1968’s cultural changes

1968: The year war came through the TV and I felt pieces of childhood ending

California Sounds 1968: 10 essential Los Angeles-infused records from a kaleidoscopic era

A timeline of anger, grief and change

Author Todd Gitlin on how to remember 1968

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.