The Blur: Does anything but where we watch separate film and television anymore? What the melding means for storytelling

It used to be easy: Movies were smart and television was dumb.

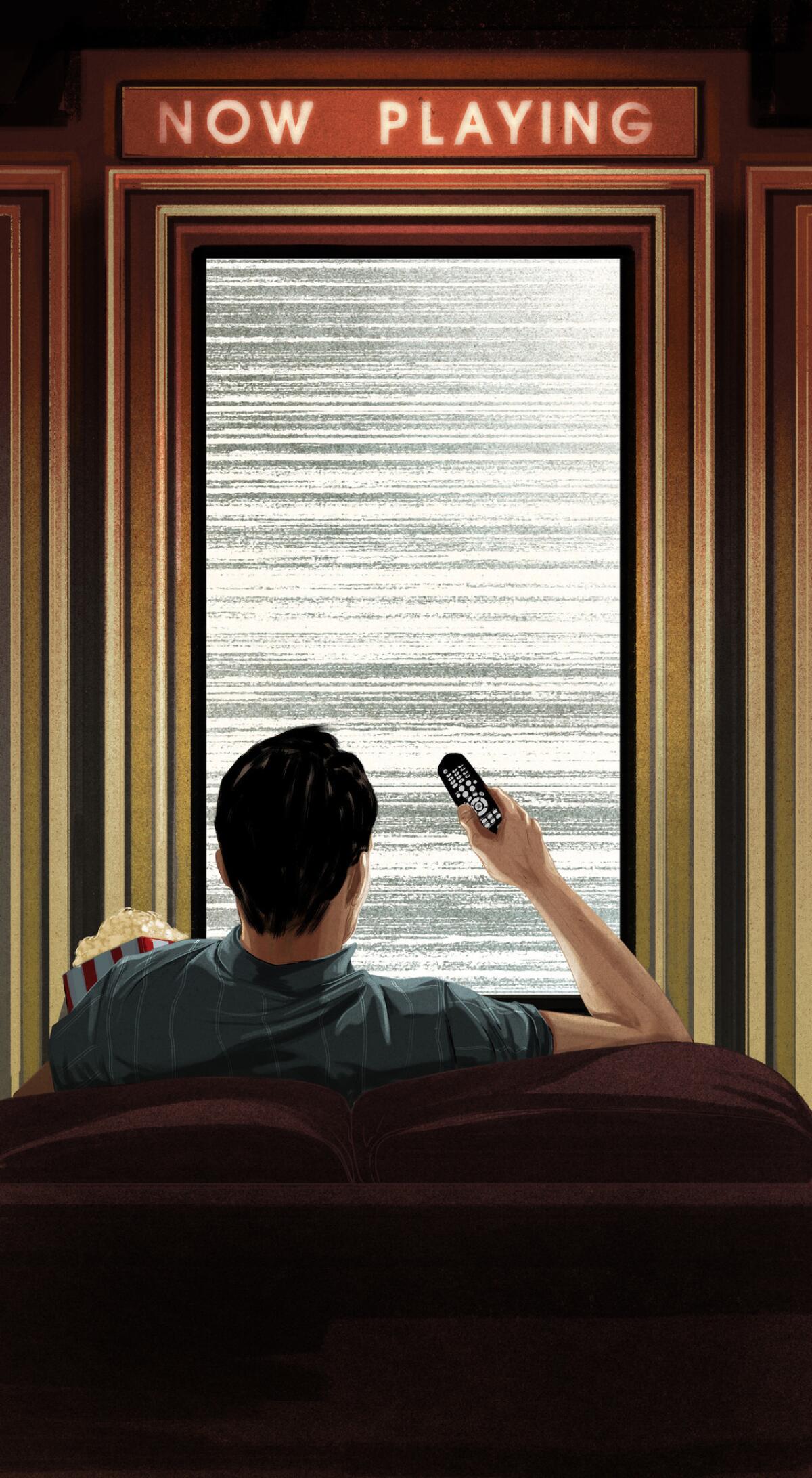

Movies were a special communal event, and television was part of humdrum home life. Television had commercials and movies did not, television was episodic and open-ended while movies told a single story. Movies could be entertaining but also high art; television might be groundbreaking or provocative, but art never entered the conversation.

No one watched television on a first date or majored in television studies, and the only movies you could watch while ironing were long gone from theaters.

Now it's not so easy. Televised series often have just as much artistry and significance as any film, and both forms come in so many shapes and sizes — and are available on so many different sorts of screens — that it is increasingly difficult to tell them apart.

The high-grossing “Captain America: Civil War,” for example, is now considered one of the most successful movies ever.

Yet while I was watching it the day after it opened, I saw a television show.

FULL COVERAGE: The blur between movies and television

A really big and loud television show, I grant you, with fight scenes fancy enough to induce motion-sickness in certain audience members seated in the third row, not to mention a body count high even by “Game of Thrones” standards. (As Captain America and the Winter Soldier fought their way through a bunch of U.S. troops they were allegedly trying not to kill, my 16-year-old and I muttered, "fatal spine injury” “fatal internal injuries,” “fatal brain trauma.")

Otherwise, it wasn't much different from many TV superhero series. Or even nonsuperhero series.

Stripped of its enormous curved screen, impressive battles and Dolby sound, “Captain America: Civil War” is the latest installment of an episodic ensemble drama that examines the tension between personal beliefs and the greater good in which moments of tragedy/peril/violence are interspersed with witty dialogue in narratives structured to accommodate future storytelling.

Just like any episode of, say, “The Good Wife.”

As digital delivery platforms morph and multiply, the nature of visual storytelling has changed and the lines that once clearly divided film from television or, for that matter, broadcast television from cable, cable from streaming, streaming from Internet, are fading, often to nonexistence.

With A-list film talent migrating more and more to television and vice versa, you can’t even call the game by the players. Instead, it’s become a matter of architecture: A film is a film if it premieres in a theater.

Except theaters, with their now-standard stadium seating or rows of Barcaloungers, are increasingly modeled on the living room — when was the last time you rubbed shoulders with a fellow moviegoer? — while many American living rooms are arranged around flat screens so large they can be viewed by cars passing in the street.

Films are almost always preceded by commercials, some for other movies, some for unrelated products, while series on cable and streaming services are commercial free.

And in a world where people increasingly watch everything on laptops, tablets or smartphones, the differences shrink, literally, to nothing.

Especially as "films" become available on your television (or laptop or smartphone) at the same time they premiere in theaters, while your favorite television show might screen its season debut at a multiplex.

This year's Christmas special of the BBC series "Sherlock" was screened in U.S. theaters for a limited two-night run just a few days after its Jan. 1 debut on PBS. In the U.K., it debuted simultaneously on the BBC and in more than 100 theaters. Was it film or television?

Conversely, as this generation of children experience the episodic Harry Potter series on their TVs or personal devices, are they watching television or film?

And does it really matter?

Television writers and performers now speak of making 12-hour movies, or in the case of shows with 90-minute or two-hour episodes like “Luther” or “Foyle's War,” a film series. Its seriousness and artistry now indisputable, TV has begun experimenting with form, technique and pacing with abandon equal to that of any indie film lab and regularly holds red-carpet theatrical premieres and Emmy-season screenings.

The film industry, meanwhile, increasingly looks to streaming services and television not just for second-tier delivery but also for narrative partnership.

In Marvel’s case, blurred lines are the business plan. While the theatrical Avengers fill the sky annually, either solo or in groups, the ABC series “Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.” plays the connective ground game. This season was driven by the same government control versus personal responsibility themes as the film.

As this generation of children experience the episodic Harry Potter series on their TVs or personal devices, are they watching television or film?

— Mary McNamara

Over on Netflix, a whole other group of Marvel heroes gather; “Daredevil,” “Jessica Jones” and the upcoming “Luke Cage” occupy an ecosystem that is part of and separate from the film franchise. Not surprisingly, DC Comics is building a similar universe.

Action-adventure films have often been serialized, and some franchises have included television — "The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles" lasted only a year but won six Emmys, "Star Wars" has the animated "Clone Wars" and "Rebels" (not to mention rumors of a resurrected live-action series created by George Lucas in 2005).

But now the blur has moved beyond the Comic-Con sphere. With their new-season, new-story construct, anthology shows like “True Detective,” “Fargo” and “American Horror Story” feel more like film series than traditional television shows. Steven Soderbergh, one of the first A-list directors to work regularly in TV, brought his high-auteur techniques to “The Knick” (meticulously broken down by critics and then in an e-book called “The Knick: Anatomy of a Series”). Even John Le Carré came back to television after 25 years in AMC’s “The Night Manager,” a six-hour miniseries filmed from one script, like a movie. (Which, if it goes to a second season, would mark the iconic spy master’s first foray into writing specifically for TV.)

But while writers, directors and performers rejoice over the freedom that television and streaming services can offer, not everyone is thrilled. High-profile buying sprees by Amazon and Netflix have left many concerned about the fate of the already-endangered art house theater, not to mention the hope of nonblockbusters ever making it into the local multiplex.

Netflix's day-and-date model (in which a film simultaneously debuts theatrically and online) has already met with backlash. Last year, four major theater chains refused to show “Beasts of No Nation,” a Netflix day-and-date release, which pretty much killed the film’s Oscar hopes.

In fact, it's the film academy, that already much-beleaguered entity, that's been tasked with pushing back the blur, at least officially.

As films like “Special Correspondents” (Netflix) and “Under the Gun” (Epix) debut the same day online and in theaters, academy by-laws have now become a factor in studio marketing plans — including decisions about who gets to see review copies of a project first. Without a theatrical release of at least seven consecutive days, a feature film cannot be considered for an Oscar. And a documentary must be reviewed by a film critic — not a television critic. (You can just imagine the testy email threads.)

This year, ESPN is putting the new cross-platform model to the ultimate test. Its five-part, 7½-hour documentary “O.J. Simpson: Made in America” debuted in Los Angeles and New York theaters Friday, a little more than two weeksbefore it moves to television; the first episode will debut on ABC on June 11 before the entire series moves to ESPN.

Though many will undoubtedly sit through the entire series in theaters, "Made in America” has absolutely been built for television. Yet it’s tough to imagine another documentary, of any length, matching its mastery and power.

Which means that in 2017, a television series may very well win an Oscar.

It does not get much blurrier than that.

MORE:

Is 'O.J.: Made in America' a TV show or a movie?

Five films that were faced with the theatrical/streaming choice

To stream or not to stream: Filmmakers face a tough choice on getting their films to audiences

Twitter: @marymacTV

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.