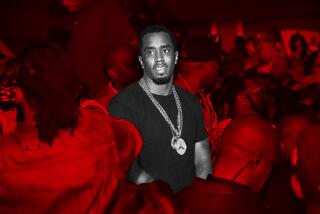

Bad Boy For Life: A look back at the rap empire Sean ‘Puff Daddy’ Combs built

Long before he was Puff Daddy the hip-hop mogul, Sean John the clothing designer or Diddy the movie star and shameless vodka promoter, Sean John Combs launched a fledgling record label that would change the course of hip-hop in just a week.

It was the summer of 1994. His label Bad Boy Entertainment had just released the hypnotic groove “Flava in Ya Ear” by Craig Mack. It shot to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Rap Songs, but more than that, it cracked the Top 10 on the pop charts in what would prove the beginning of hip-hop’s dominance of mainstream music and American pop culture.

Within days of Mack’s hit, Bad Boy released the debut from its other flagship artist, a burly former crack dealer with a poetic flow who called himself the Notorious B.I.G. “Juicy” became an instant rap classic and cemented Bad Boy’s spot as a new leader in the genre.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

“It was a gamble,” Combs said in a 1995 interview with The Times. “But whatever I do, I want it to be groundbreaking. I think of everything I do as history in the making.”

Whatever I do, I want it to be groundbreaking. I think of everything I do as history in the making.

— Sean John Combs, rapper

The gamble clearly paid off. Combs is now known as one of rap’s early enterprising magnates, overseeing an empire that includes fragrances, beverages and a cable network.

“Bad Boy showed us it can be deeper than music,” said Bad Boy artist Machine Gun Kelly. “It showed us we can make our own clothes, make our own cologne. We can make bigger moves than music.”

On Wednesday, Combs, 46, added to his legacy when he surprise-released his album “MMM” as part of a larger push to reach out to a new generation of rap fans. The artist is also relaunching his imprint and has yet another anticipated album in the works.

Judging by the reception he received at the recent BET Awards, the time is right for Bad Boy to reemerge. He killed it on stage with the label’s top acts performing some of the label’s biggest hits: “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down,” “Mo Money Mo Problems,” “All About the Benjamins,” “Peaches and Cream” and “Love Like This.”

Artists who ruled the airwaves throughout the ‘90s and early 2000s — Faith Evans, Mase, Lil Kim, the Lox and 112 — charmed the audience of R&B icons and new rap upstarts out of their seats. The crowd sang along in unison, the music part of their DNA.

Bad Boy Entertainment videos

That BET moment is considered among the best rap reunions ever, maybe because it represented a golden age in hip-hop when rappers knocked pop stars off the charts and a kid named Combs became a music mogul almost overnight.

This is the story of Bad Boy, and how a college dropout went on to become one of rap’s most influential players.

It Was All a Dream

Combs, born in Harlem, first made a name for himself on the campus of Howard University in Washington, D.C., in the late 1980s by throwing weekly parties, which became the place to be and lured celebrities including Doug E. Fresh, Slick Rick, Guy and Heavy D.

“He had a great attitude, a great energy,” said Harve Pierre, president of Bad Boy Entertainment, who met Combs during his sophomore year at Howard. “He was known for dancing and riling the crowd up — things he still does to this day.”

Combs may be the first to admit he was — and perhaps still is — unapologetically arrogant and self-promoting. In his early 20s, he begged his way into an internship with Uptown Records after Heavy D got him a meeting with label head Andre Harrell. Combs would make the four-hour commute from Howard to New York for the unpaid gig, often getting permission from professors to skip class.

He quickly rose up the ranks helping Harrell shape Jodeci and Mary J. Blige, eventually producing for Father MC, Christopher Williams and Blige. Harrell promoted him to vice president of Uptown’s talent and marketing divisions. But the gig wouldn’t last long. The more success Combs found at the label, the more tensions grew between him and mentor Harrell over the progress of Bad Boy, which Combs was hoping to get distributed through Uptown. He was eventually fired.

But Combs’ burgeoning imprint caught the attention of prolific record executive Clive Davis, and he cut a deal with Combs (reportedly worth $10 million to $15 million) to distribute the label through Arista Records. Combs brought over B.I.G., then a hungry 19-year-old MC he read about in Source Magazine and signed to Uptown. Mack was also allowed to follow.

Bad Boy’s first roster was fail-proof, with Puff meticulously handpicking talent to satisfy a breadth of tastes. B.I.G. brought hard grit that matched the aggressive gangsta rap brewing on the West Coast post-N.W.A. Mack offered the tongue-twisting, ferocious but whimsical rhymes that earned Busta Rhymes early praise. With Total, he found a streetwise female trio of spitfires reminiscent of TLC. Faith Evans spun out a more refined version of the hip-hop soul that launched Blige. And 112 offered a sexier take on harmonious male R&B groups like Boyz II Men and Hi-Five.

“He had a great blueprint on how to introduce the next,” said Quinnes “Q” Parker of 112, who Puff signed at Evans’ urging after they auditioned in Atlanta. “He used B.I.G. to introduce 112, he used 112 to introduce Mase,” Parker notes. “He used B.I.G. to help introduce Total. [We] wrote songs for Faith Evans, and she wrote songs for our album.”

“They were trendsetters. It was due to Puff’s ear and his ability to pick voices that were like no other. Biggie, Faith, Slim of 112 were just special voices,” said Dawn Richard, a former member of Danity Kane and Diddy-Dirty Money. “These were signature voices [and] so different from what was going on at the time in music.”

Bad Boy’s success was lightning fast, thanks to Puff’s in-house production team, the Hitmen, weaving together albums stuffed with grooves that layered soul-stirring R&B samples with speaker-rattling hip-hop (Dr. Dre mastered this years before) and Combs’ slick marketing tactics, a skill the born hustler had perfected during his days as an ambitious, enterprising business major at Howard.

“It was fun. It was new,” Evans remembers of the label’s earliest days. “That’s the one thing I can say despite … plenty of ups and downs. It was a whole lot of fun, I’m not going to lie. Every day was something different.”

It was a whole lot of fun, I’m not going to lie. Everyday was something different.

— Faith Evans, singer

Combs assembled armies to tackle the streets of New York with fliers or march with picket signs and flags (rap labels, especially, relied on street team marketing — a tactic still widely used today across genres).

To promote B.I.G. and Mack to music journalists, Puff came up with the ingenious idea of the “B.I.G. Mack” sampler — a play on the popular McDonald’s burger — which included a cassette, photos and one-sheets of the two acts in a package reminiscent of the fast-food item.

“We were the first in many things. We started that whole street team type of [promotion],” Pierre said. “We were trying to get maximum exposure on what we’re doing. We were like the first people to fly a plane over [black music convention] Jack the Rapper. People talked about it for weeks.”

“I remember the first promotion. It was a white card with black writing [that said] ‘Who is 112? We got next,’” Parker said. “He would flood the streets of New York City with just this card.”

Puff also had an unwavering vision for developing his acts, something that stretched back to his days at Uptown with Blige and Jodeci.

“The strategy behind 112 was taking the personality of the president. Puff had established himself at the time as fashion forward, he was swagged-out before ‘swag’ even became a word,” Parker continued. “He made leather and being a ‘Bad Boy’ cool. So when he found these four guys who had not really been anywhere, from the projects of Atlanta, I think he sprinkled a lot of himself into [us].”

“He used to take me to get my tans because he told me I was too pale when I first signed,” Evans laughed. “He obviously had his vision of what he wanted to present. He told me, ‘You’re going to be my mature grown woman balladeer.’ Even though my blond hair probably inspired people, I hated some of those earlier [hair] styles. But … I wasn’t in the music business, so I’m thinking if they dyed it, they probably knew what they’re doing. For whatever it was worth, it worked.”

Combs turned out to be right: In its first three years, Bad Boy logged an estimated $75 million in album sales.

Mo Money Mo Problems

Despite its success, and likely because of it, Bad Boy was embroiled in a bitter, media-fueled rivalry with another major player on the rap scene, the L.A.-based Death Row Records, founded by Dr. Dre and bodyguard-turned-impresario Marion “Suge” Knight.

By the end of 1996, Death Row’s flagship artist, Tupac Shakur — B.I.G.’s former friend, who accused him and Combs of setting him up to be robbed and shot in a 1994 attack and boasted that he’d slept with B.I.G.’s wife, Evans, on a vicious diss record — was gunned down in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas.

The killing shook the industry, and whispers around the industry placed the blame on Bad Boy.

Six months later, while in L.A. for the 1997 Soul Train Awards, the Notorious B.I.G. was gunned down after leaving an after-party. Sixteen days later, his sophomore album, “Life After Death,” was released. It reached No. 1 and would go on to sell 10 million copies.

“The only way you can look at it is tragic. Tragic and senseless,” Evans says. “But I don’t think that situation was the result of being in the music business. It’s a little deeper than that. I think all the things that came with it definitely added to the hype of things. The whole media element, and people being able to say what they think and not be accurate.”

“But the bottom line is it was two senseless tragedies that were the result of people not being good people,” she continued. “I can’t say the music business is the reason why. Losing my husband [is] something I think about every day. But I don’t blame that on Bad Boy -- at all.”

The bottom line is, it was two senseless tragedies that were the result of people not being good people ... . But I don’t blame that on Bad Boy -- at all.

— Faith Evans, singer

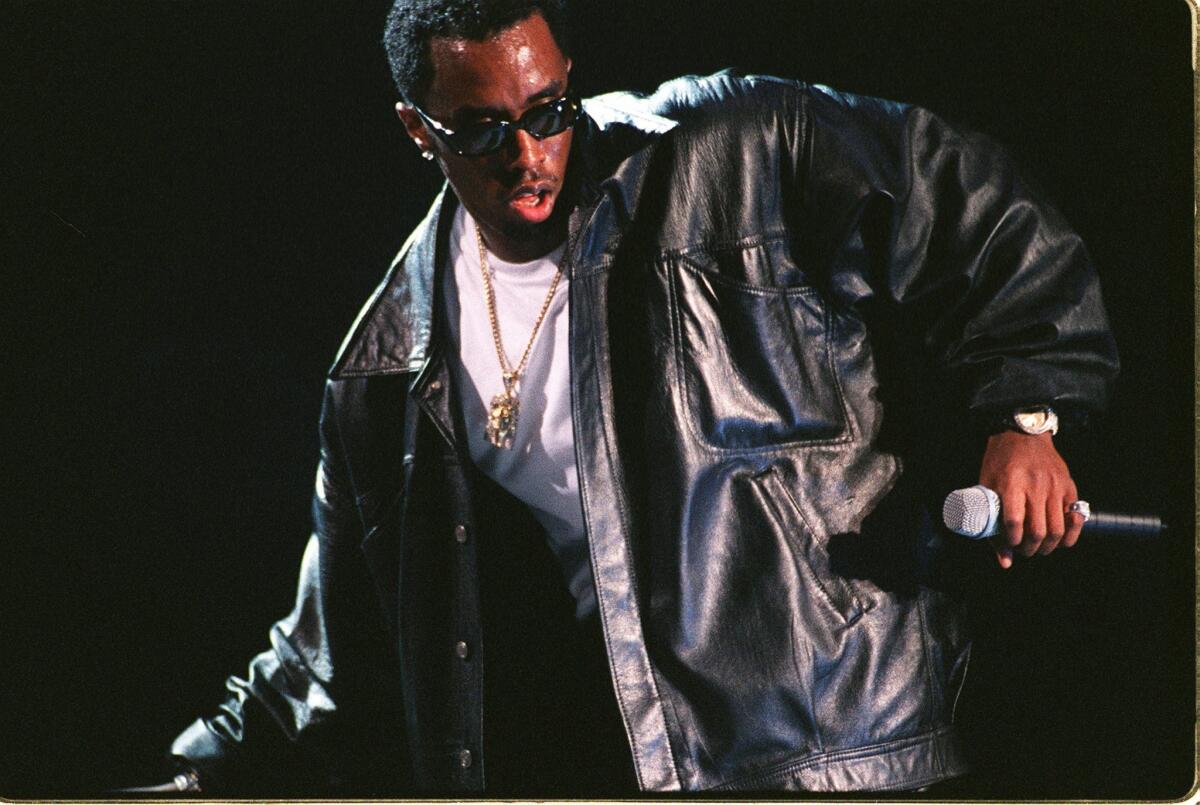

After years of sharing the spotlight with his acts – Puff inserted himself on the records he produced and music videos he directed, to much criticism – he took on a new role: Bad Boy’s latest marquee act.

Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down

Before B.I.G. was killed, Puff made his debut with “Can’t Nobody Hold Us Down.” The single helped push his newest protege, innocuous Harlem rapper Mase, further into the spotlight.

The single featured a glossy video packed with flashy dancing and fabulous fashion to match the decidedly more pop-R&B crossover approach. The record took off and sat at No. 1 on the pop charts for six weeks.

Though reeling from the loss of B.I.G., 1997 was a banner year for Bad Boy.

Out of the 10 songs to reach No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, four were from the label, and for nearly half of the year the top spot was occupied by a massive Bad Boy hit: “I’ll Be Missing You,” a tribute to the slain rapper, topped the Hot 100 for 11 weeks (only to be unseated by B.I.G.’s “Mo Money Mo Problems”).

The hits continued with albums from Evans, 112, Mase and Carl Thomas going platinum.

But the further Puff thrust himself into the spotlight, the more his relationships with his artists would sour, and 10 years after its launch, Bad Boy was seemingly in disarray.

Mase had thrown in the towel on music, hallmark acts like Evans, Total and 112 had exited and a new generation of acts — Shyne, the Lox, Loon, Dream, G. Dep, Black Rob — like Craig Mack before them, didn’t make it far under the label.

“Where it started to strain … was when he started to focus on his artistry and him being not only the president and CEO but now an artist on the label,” Parker admitted. “The more the focus started to go on him, the other artists under the label started to feel either neglected or just felt like this is the time … to go and kind of sort our own way.”

Evans adds, “I left for different reasons. I felt like it was time for me to do something different, and at that time I wasn’t getting what I felt from the other end what I was putting in, as far as being dedicated. Puff wasn’t in that same place as far as being a record executive; he was dabbling in other things at the time.”

Frequent shuffling and strained artist relations, paired with Puff’s controversies — his assault on Steve Stoute over Nas’ “Hate Me Now” video and a highly publicized trial stemming from a nightclub shooting (he was acquitted; Shyne served 10 years behind bars, with critics of Combs speculating he took the rap for the crime) — cast a dark cloud over the label.

The Internet is rife with theories that the label, and Combs, are cursed.

Former Bad Boy artist Mark Curry lobbed a number of startling accusations toward Combs in his book, “Dancing With the Devil: How Puff Burned the Bad Boys of Hip Hop.” One of them? That Biggie resorted to selling dope and homemade duplicates of his platinum album from the trunk of his car for spending money.

In Evans’ memoir, she’s frank about detailing her battles for publishing royalties and other contractual hurdles. “I learned now that I’d better be on top of my business,” she says with a laugh.

Pierre, who rose from intern to president at the company, said Combs has unfairly gotten a bad rap.

Bad Boy is a big brand, and it’s a big name. There’s a standard that you have to live by.

— Harve Pierre, president of Bad Boy Entertainment

“Bad Boy is a big brand, and it’s a big name. There’s a standard that you have to live by. People just expect everything that Bad Boy does, because of the early ‘90s; everything has to be double and triple platinum,” he said. “But you go to any other record label, and they have records come out that you never even heard of. They have albums that do well, and albums that do bad. But when it comes to Bad Boy, if something doesn’t do exceptional, than something’s wrong.”

Bad Boy for Life

Puff’s 2006 album, “Press Play,” his first in five years, capped a year that revitalized the label by folding in more dance-pop sounds.

He was on his third rebranding (we went from Puff Daddy to P. Diddy to Diddy) and would successfully expand his stock to include weighty film roles (“Get Him to the Greek,” “A Raisin In the Sun”), a hot-selling vodka line and reality TV, taking the “Making the Band” franchise and churning out three groups — including platinum urban-pop girl group Danity Kane — and an “Apprentice”-style show on which he looked for a personal assistant.

“I heard rumors that he was the devil incarnate and that the label was one of those that you have to be careful of. But all I saw was talent,” said Richard, who landed in Danity Kane on MTV’s hit “Making the Band 3” (Combs created a hip-hop collective and a male R&B group on other seasons of the hit show) and the hip-hop fusion project Diddy-Dirty Money alongside Puff before going solo.

“He was trying to transition Bad Boy into the pop world. I think it was smart of him to use TV because people wouldn’t have associated Bad Boy with pop at the time,” Richard said. “He knew he had to sell something and show people a different view of Bad Boy for them to respect it and take the pop lane seriously.”

More than 20 years later, Bad Boy’s glory days of churning out platinum hit after platinum hit are behind them. But the label is keeping the torch lit, and finding success, with acts like Machine Gun Kelly, French Montana and Janelle Monae.

Following the surprise performance at the BET Awards, there’s been nonstop buzz of a reunion tour, and Combs is teasing the sequel to his own Grammy-winning debut, “No Way Out” (billed as his last album). “MMM,” released as a free gift to fans on what was his 46th birthday, serves as a prelude to the forthcoming album. Bad Boy is also being relaunched under a new deal that will see Epic Records introduce a new generation of artists and provide services such as promotion, marketing, sales and distribution to the imprint.

“I had people telling me that Bad Boy is dead … [that] there’s a black cloud over Bad Boy,” French Montana recalled of signing to the label in 2012. “Puff hasn’t sold me a dream yet. Everything he told me, he brought to the table and came through with it.”

Nearly a quarter-century after he dropped out of Howard, Combs returned to the campus last year, this time draped in full graduation regalia. He received an honorary doctorate from the prestigious historically black university, and he delivered the commencement address, which was broadcast on his Revolt network.

“Some of my biggest successes come from some of my biggest failures,” he said. “I had two choices: Either I was going to sit in that failure and give up, or I was going to make a decision and step out of the darkness.”

Follow me on Twitter: @GerrickKennedy

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.