Q&A: Michael Bublé and Seth MacFarlane on what made Frank Sinatra a ‘wonderful monster’

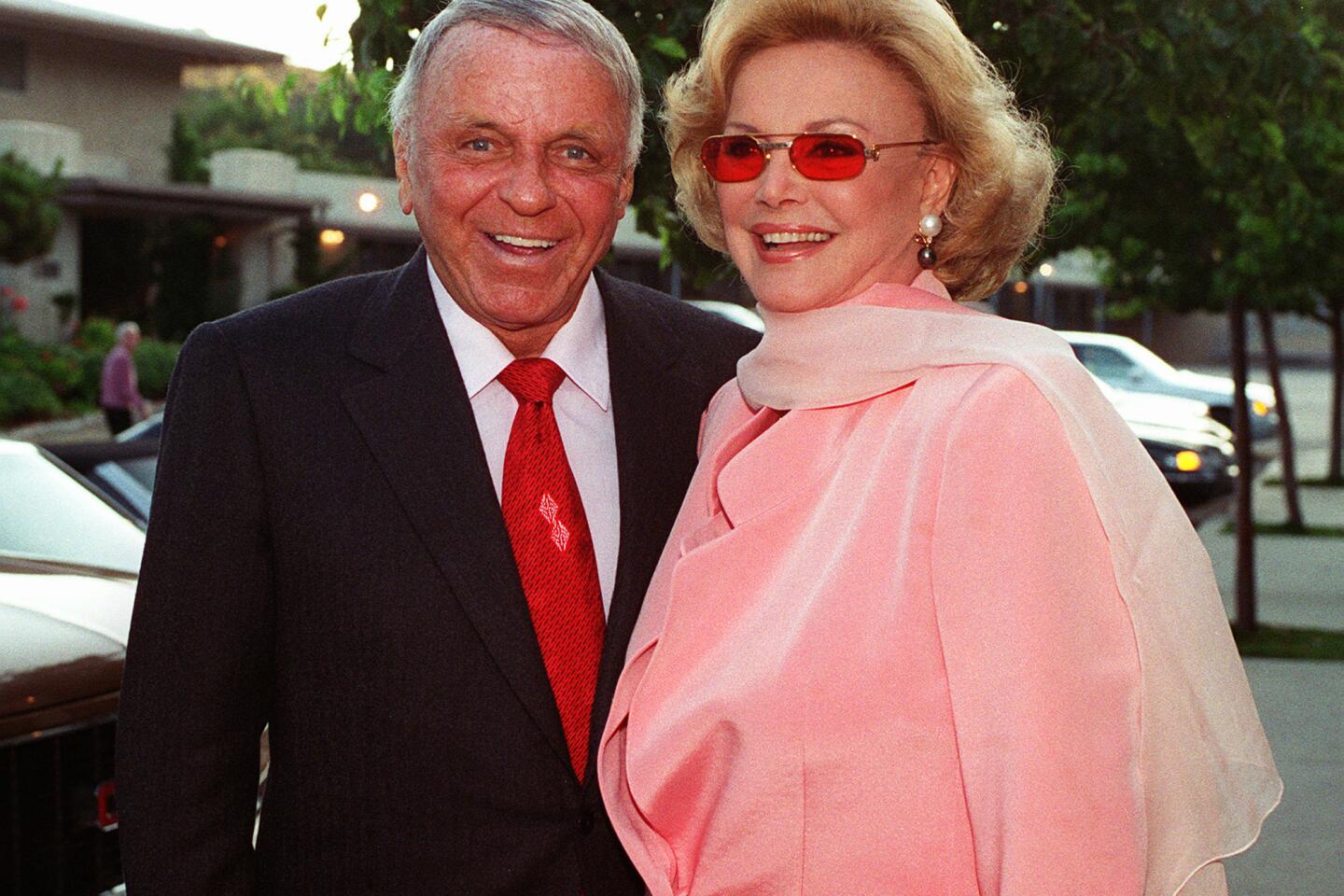

Frank Sinatra in 1984 at the Universal Amphitheatre.

Frank Sinatra was born 100 years ago but wasn’t around to see the last 17 of them. Yet his effect on what it means to be a pop star is so great that it often feels as though the legendary singer has never left us.

Jay Z’s swagger, Bruno Mars’ fedora, Taylor Swift’s ode to New York City — all are traceable, to some degree, to the crooner from Hoboken, N.J.

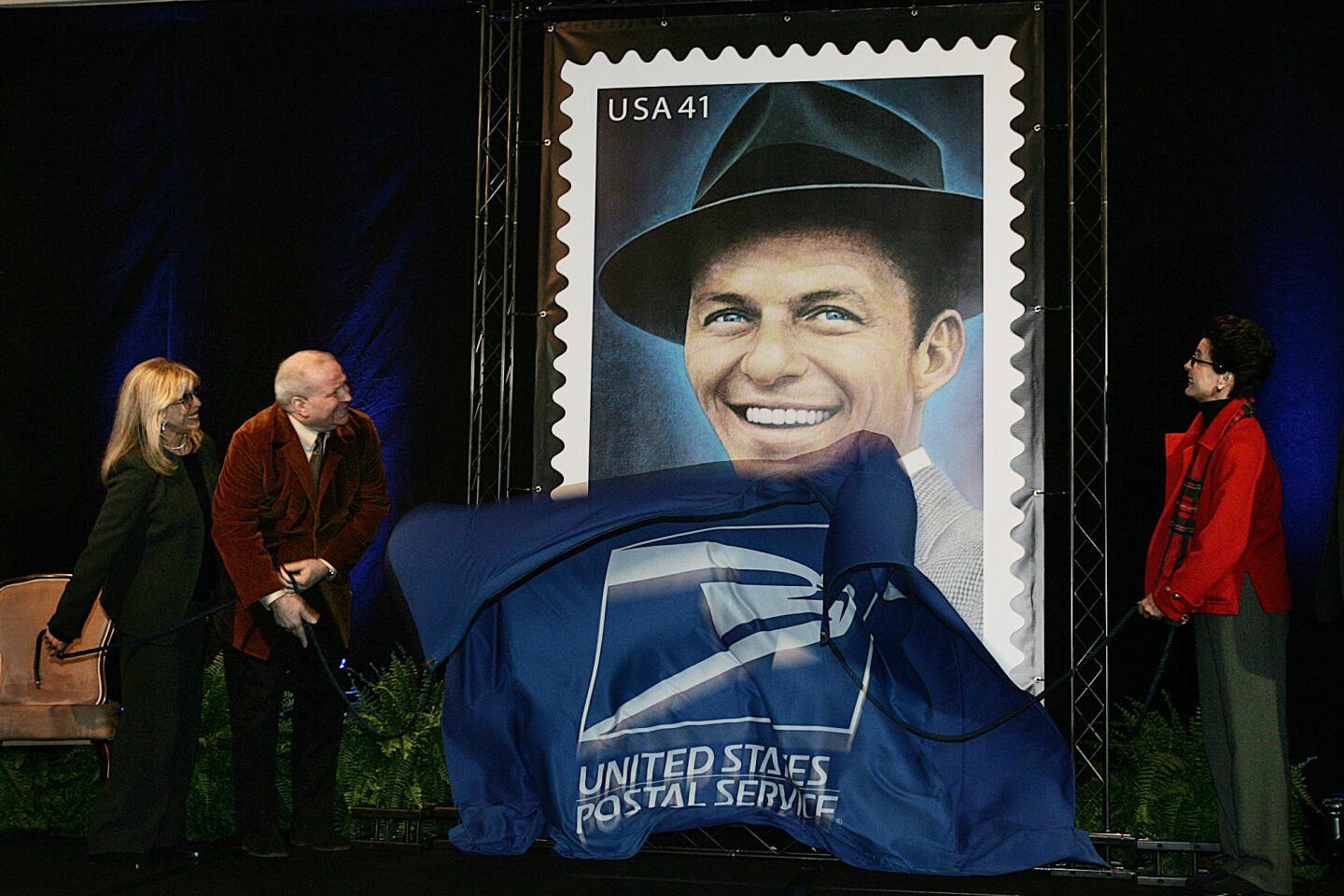

On Wednesday night, two of his most ardent admirers — Michael Bublé and Seth MacFarlane — will team up for a concert tribute at Club Nokia at L.A. Live. The benefit show follows the Grammy Museum’s recognition of Sinatra at its annual Architects of Sound gala, as well as Wednesday’s opening of a new multimedia exhibit, “Sinatra: An American Icon.”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

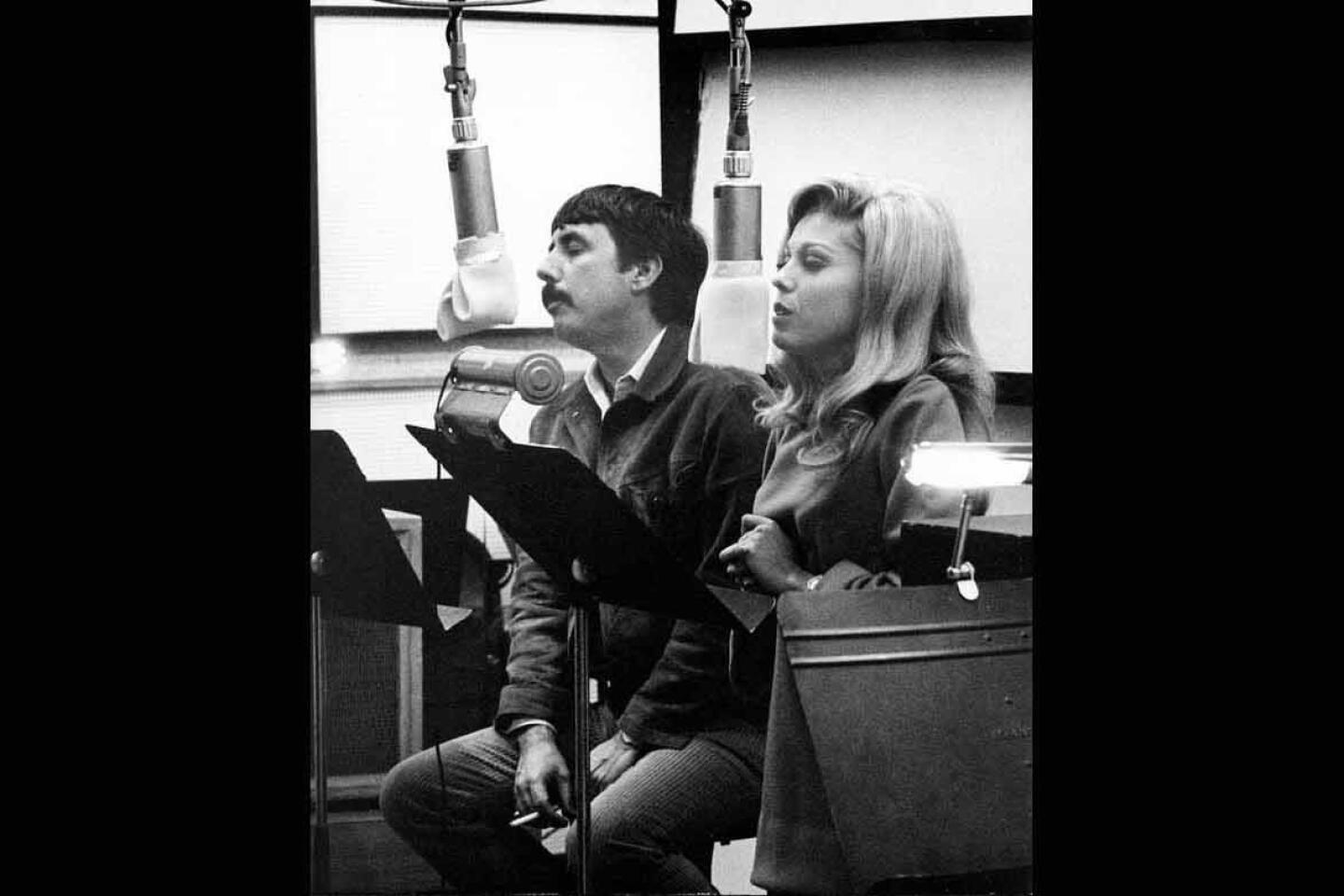

On Sunday morning, I rang MacFarlane, who just released his latest album, and Bublé, who’s in L.A. recording a new one, to discuss the Chairman of the Board. These are excerpts from our conversation.

How large does Sinatra loom over what you both do? If you’re a guy wearing nice clothes singing standards, is Sinatra an immovable object you simply have to address?

Seth MacFarlane: I think if you drop the nice clothes, then really, you’ve got your own thing going on.

So that’s all it takes.

MacFarlane: Look, this was possibly the greatest singer of popular music of all time. For me, that’s always in the back of my mind. The trick is to sing different songs than he sang and to not try to duplicate his performances. You put your own stamp on it, and that kind of keeps you in the clear.

Michael Bublé: To be completely — and pardon the pun — frank with you, I have ripped off everything I could possibly rip off from Frank Sinatra, from Dean Martin, from Bobby Darin, from Vaughn Monroe, from all the singers. I’ve stolen as much as I could, and I felt like if I did that I could pass it off as research. You sort of realize Sinatra was Sinatra, but you have to do the very best you can with what you have and make it your own.

MacFarlane: They say good artists borrow, great artists steal.

Bublé: It’s impossible not to be inspired by the guy — this wonderful monster, this guy whose voice and whose control was incomparable.

How was each of you introduced to his work?

MacFarlane: I came into it in an oddly backward way. I was a big fan of film scores when I was a kid, as well as big-band jazz from the ‘40s and ‘50s. But it was really the orchestra I was interested in, the creative mixtures of sounds that could be achieved with an orchestra. And really, during that time — the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s — that was when it was really all happening. I mean, what MGM alone was doing was something that had not been done before or since. I hadn’t really sat down and listened to a Frank Sinatra song seriously until I was in college. And what struck me initially were the orchestrations; it was Nelson Riddle, Gordon Jenkins, Billy May. The more I heard, the more I realized there was something very, very special going on in the vocals, something that no one else had done.

Bublé: My grandfather and I, we had a great relationship, and he would sit with me and play these records. I listened to a lot of Bobby Darin as a kid – 7, 8 years old. Dean Martin was a huge one. We’re an Italian-Canadian family, you know, so a lot of those great Italian singers — Tony Bennett — were played through the house.

The Sinatra that I met first wasn’t the “Come Fly With Me” Sinatra. The Sinatra I met was the Sinatra singing with the Pied Pipers — really early, really incredible, beautiful, sweet, young voice. I would go and take songs like “Stardust” and “My Melancholy Baby,” these really old recordings, and I would put them on cassette, and when I went to bed, I would listen to them over and over and over and over.

Sinatra’s devotion to his favorite arrangers was well documented. On his live album “The Main Event,” he shouts out each song’s arranger at the top of every tune, even though few in the audience might have cared.

MacFarlane: I think at one time people did. Guys like Nelson Riddle and Gordon Jenkins had their own careers independent of Sinatra. Nelson Riddle had his own orchestra; Gordon Jenkins wrote “Manhattan Tower.” For me, the biggest loss in popular music today is the absence of the orchestrator as a known entity that is as important a part of the song as the composer and the vocalist.

Bublé: I feel like you were watching me yesterday, Seth. I just had an hour-long conversation about this. Marc Shaiman and I are doing a record together right now, and I said to him, “You know what’s changed, Marc? The arranger.” And it’s just what you said. The arranger wasn’t just an arranger; you didn’t just call him and throw him some dough and say, “Make an arrangement.” He produced the record. Don Costa produced those [Sinatra] records, you know what I mean? It was his record, along with Frank as the star.

MacFarlane: That’s the perfect way to describe it in modern terms. [The arranger] has been replaced by the producer.

The arrangements on any given Sinatra album did a lot to inform its character. And Sinatra put across a variety of characters throughout his career. Michael, you seem most drawn to the swinger. For you, Seth, it’s the saloon singer.

MacFarlane: I think we both live in both parts of the musical language. But the thing I suppose that’s very special about albums like “Only the Lonely” and “In the Wee Small Hours” — again, it goes back to the orchestra. Those rubato ballads, particularly the ones in the late ‘50s, are really the apex of what the orchestra was allowed to do; they almost feel like you’re listening to a classical piece. It’s hard to take a song or a recording like “Spring Is Here,” which is one of my favorite Sinatra ballads that Nelson Riddle arranged, and categorize it in a genre. Is it jazz? Is it classical? It’s not really any of those things. It’s its own beast.

Bublé: Public perception is a strange thing. I don’t think people have a clear and honest understanding of who a human being is through public perception. Frank Sinatra was a complicated man; he was insecure and macho and romantic and all of the things that Seth is and I am and we all are. So to look at any certain part or age or caricature of him and to be drawn to that — that wasn’t something I ever felt.

You respond to the idea that he embodies all those qualities and impulses at the same time.

Bublé: I think so. But again, it has to do with the perception. There’s a man and a myth.

MacFarlane: There’s the question of who this guy really was. Sinatra was a guy who constantly had to keep moving; he was terrified of idleness, terrified of sleep, terrified of anything that represented inaction. And he had to constantly be surrounded by people. That side of it is hard for me to lock into; I value solitude enormously. But this idea of having to keep working at a breakneck pace is something that I connect to.

And the more I learn about Sinatra’s life, the more I feel those moments in the recording sessions were when he was allowing himself to drop all of his walls and be the most naked and the most honest. I think that’s the thing above all else that separates his recordings from his contemporaries’. You don’t really hear that degree of depth from anyone but him.

Let’s finish by talking for a second about late Sinatra. Here was someone who clearly had a lot of disdain for what pop had become but who also seemed wary of being left behind. His records from those years feel defined by this complicated mix of desperation and nobility.

MacFarlane: Those are interesting recordings. There’s no question that they’re successful and unsuccessful alternately. But there’s also no denying that it’s Sinatra bringing Sinatra to the table in each one of them. There’s this recording of “Downtown,” the Petula Clark song.

Bublé: [Singing] “Unnhh-town!”

MacFarlane: Right. It’s nothing short of bizarre. I mean, there are these odd vocalizations that can only be explained if you were sitting in that room at that time. Or there’s his recording of “Just the Way You Are,” the Billy Joel song, which he does well. He gets into the song, and it’s hard because his whole approach in his prime was to start with the lyric and figure out, “Why did they write it, and how do I inhabit it?”

But to do that in the best possible way, you need a lyric that is openly sentimental or openly expressive in the upbeat tunes. And that just became harder and harder as music evolved. Or de-evolved. It’s a strange time. He was trying to fit in, and it was kind of a square peg in a round hole. But he was fearless about it.

Bublé: Dude, you answered a really tough question with great grace there.

MacFarlane: I’m just hung over, man.

ALSO:

Spotify woos Joanna Newsom with invite: ‘We’d love to work with her too’

Van Halen hits pause on the bickering and rocks hard at the Hollywood Bowl

Kanye West posts two new songs on Soundcloud

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.