Kendrick Lamar owes himself more than lifeless corporate gigs

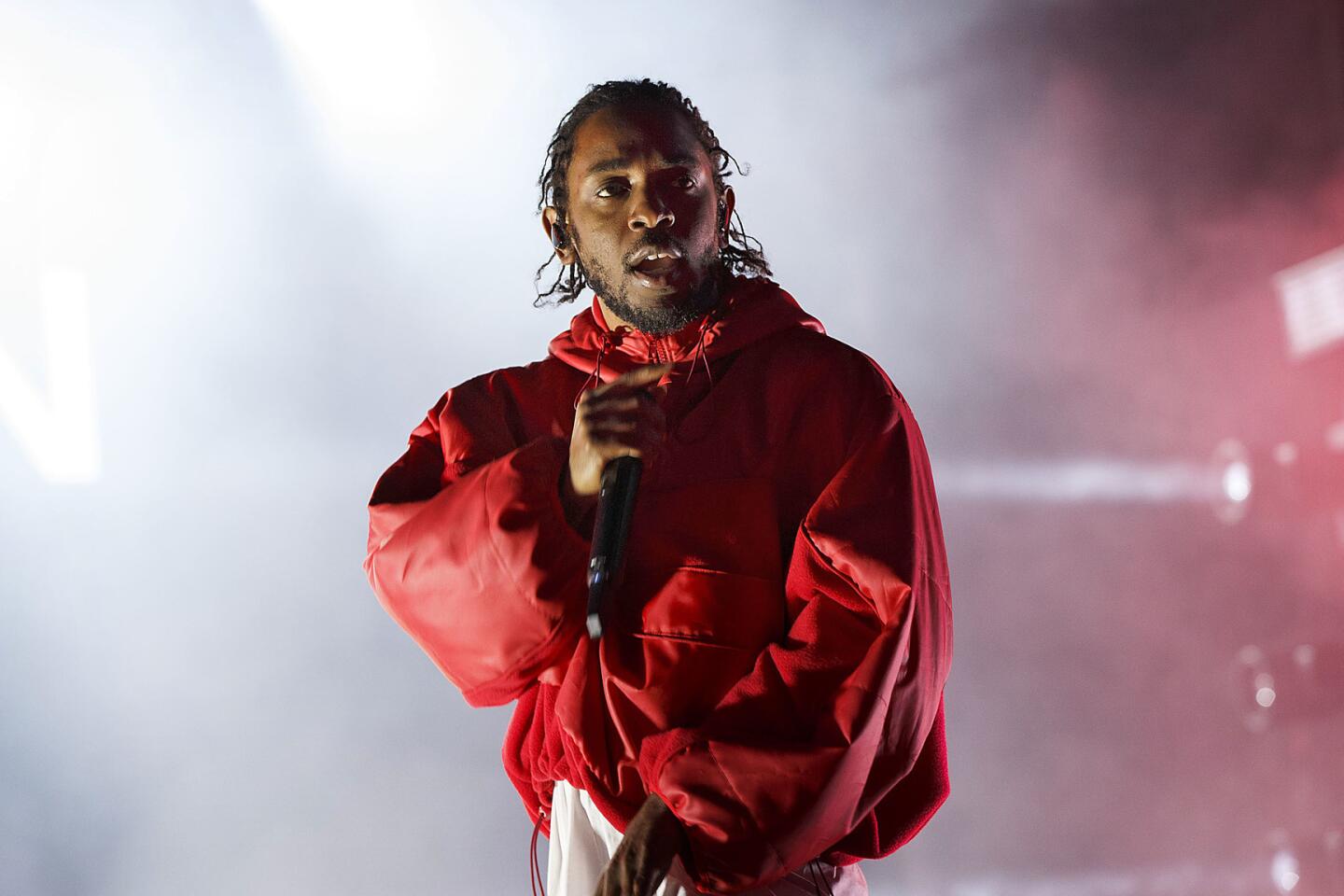

On tour last year behind his hit album “Damn,” Kendrick Lamar performed every night on a stage largely swept free of distractions.

The bare-bones production was designed to focus attention on the Compton rapper’s densely worded songs about race, identity and the alienating effect of success, and Friday night those themes carried through to Lamar’s show in downtown Los Angeles.

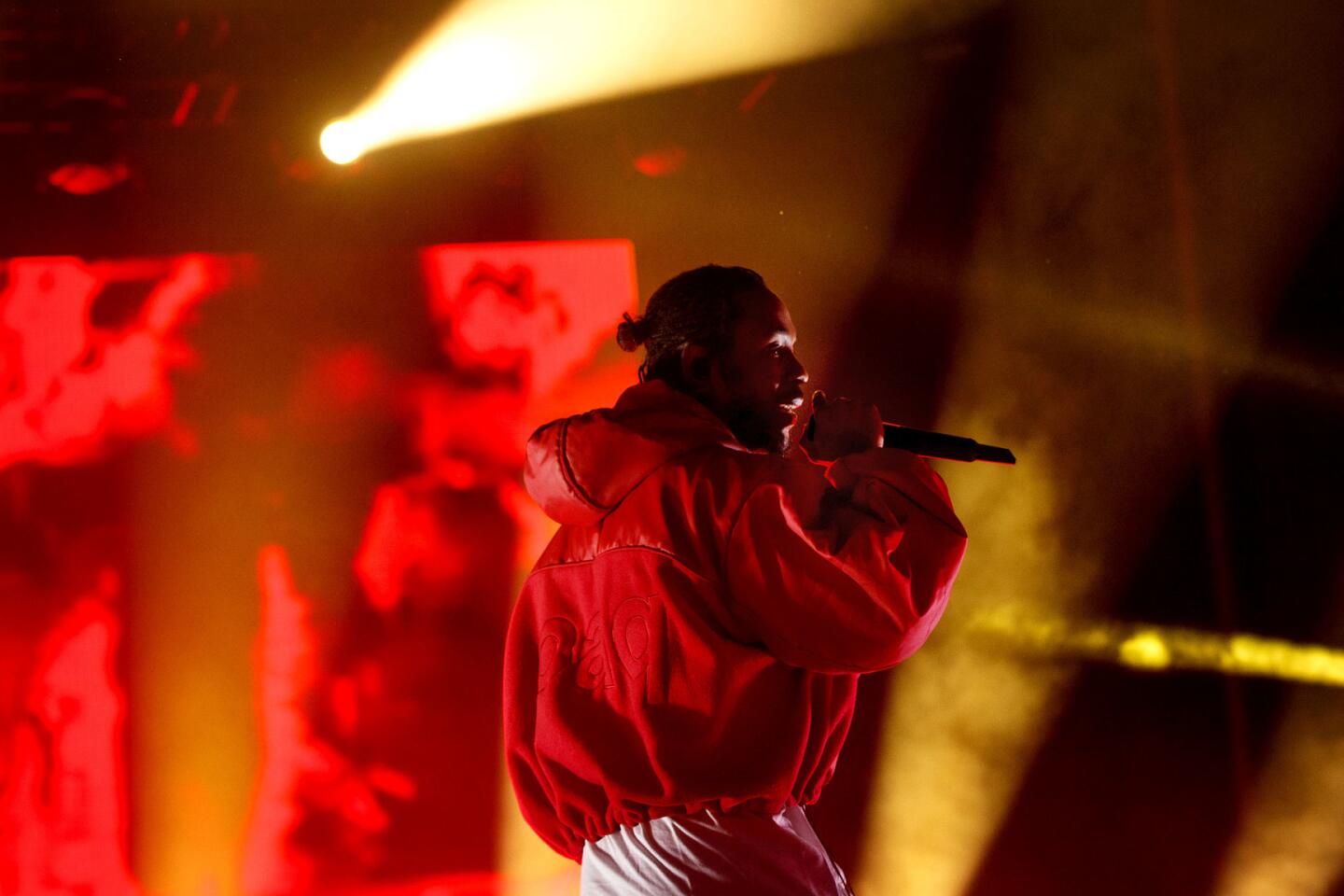

If the presentation was familiar, though, the atmosphere couldn’t have been more different: Instead of a darkened arena or the open expanse of Coachella’s polo field, Lamar’s venue this time was the central plaza at the L.A. Live complex, with its hard concrete surfaces and its visual jumble of corporate logos.

The occasion? A special event, open only to American Express cardholders (and at least one journalist), meant to hype the NBA All-Star game Sunday evening at Staples Center, just across Chick Hearn Court from where Lamar’s stage was set up.

Anyone acquainted with Lamar, who at 30 has already spent several years being called the most important rapper alive, might reasonably think that he’d be the guy to prove a great concert can happen in such a demoralizing setting. After all, it was only a few weeks ago that Lamar brought real intensity as a performer to an otherwise grim Grammy Awards ceremony (in which “Damn” won several rap prizes yet senselessly lost album of the year to Bruno Mars’ “24K Magic”).

But a great concert is not what took place Friday.

Dutiful and machine-like, this was by far the least engaged I’ve ever seen Lamar onstage, with canned banter about which side of the crowd was louder and tired eyes that seemed to search for the exit between every song. Perhaps he was simply exhausted — an understandable scenario, given how busy he’s been lately. This month Lamar released the sprawling soundtrack album to “Black Panther,” for which he contributed to all 14 tracks.

And right now he’s in the middle of a European tour; Lamar flew home to L.A. after a gig Thursday night in Germany and is due back in London to play Wembley Arena on Tuesday.

Yet there was also something deadening about the harshly commercial environment, as though the inescapable branding efforts of Toyota and Herbalife and New Era and TNT and Microsoft and the NBA were bearing down on Lamar’s small protected space, depriving it of the oxygen needed to communicate.

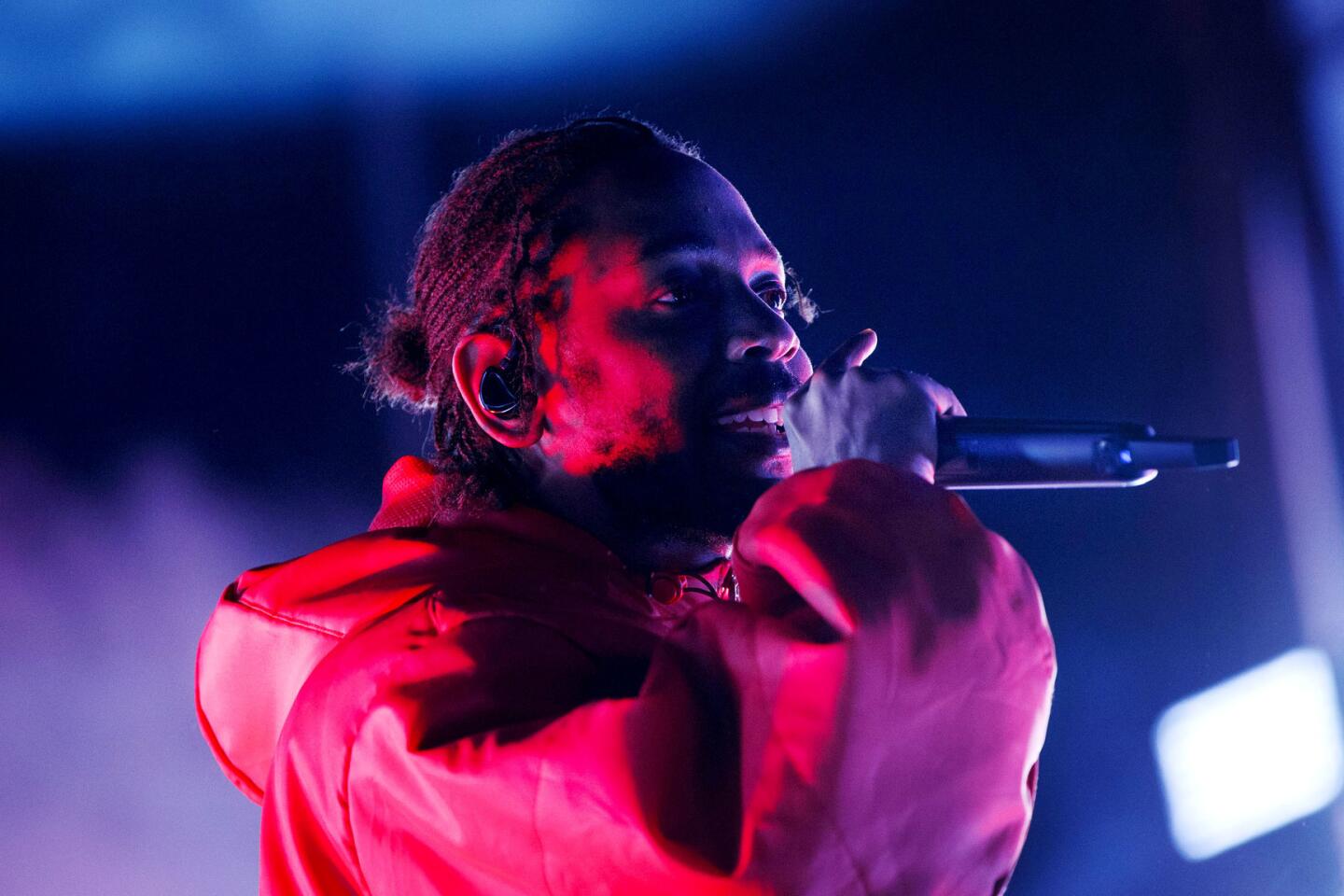

The 45-minute performance was basically a truncated version of the “Damn” show, with that album’s big singles (including “Humble,” “Love” and “Loyalty”) as well as oldies like “King Kunta” and “Swimming Pools (Drank).” As at Staples and Coachella, a live band sounded like it was accompanying the rapper, though no musicians were visible onstage.

And Lamar’s rhyming was never less than proficient, even when a song diverged slightly from its studio arrangement, as in “Collard Greens,” his duet with Schoolboy Q, which here got an infusion of flowery jazz guitar.

But the fiery sense of purpose that typically propels Lamar was nowhere to be found; his robotic delivery and low-impact moves gave him the appearance not of an impassioned artist — the man on the Grammys pondering threats to black power in front of a giant American flag — but of a lowly content farmer eager to finish his shift before clocking out.

So why agree to the job?

Plenty of A-list artists have plenty of reasons for doing corporate events these days. Some align with powerful brands to get access to the kind of marketing money that record labels can no longer provide. That seemed to be Lady Gaga’s motivation, for instance, when she teamed with Bud Light for a series of well-promoted, faux-edgy club gigs in 2016. Ditto another All-Star weekend concert put on by Adidas, which brought acts such as N.E.R.D. and Kid Cudi (and an unannounced cameo by Kanye West) to a garishly branded warehouse space in the Fashion District.

For Lamar, doing business with American Express represented a philanthropic opportunity, at least in part: According to a representative, all proceeds from Friday’s concert — for which tickets cost $75 — went to Big Brothers Big Sisters of Greater Los Angeles.

Given that commitment to the greater good, you could be tempted to forgive Lamar’s autopilot approach, especially since the show came just as his label, Top Dawg Entertainment, announced that it would host free screenings of “Black Panther” for young residents of several public-housing developments in Watts.

And it’s not as though Lamar debased himself by encouraging anyone to use his corporate partner’s product (as more or less happened when Lady Gaga carefully poured a can of beer over her head at Silver Lake’s Satellite).

Still, it was undeniably dispiriting to see Lamar coast through “XXX” — a complicated meditation on institutional racism — for the amusement of a privileged crowd being rewarded for its choice in plastic.

Some riches should be kept from cheapening.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

The Grammys were set for change, but that’s not what happened

A bad romance? Lady Gaga and her corporate partner make an iffy splash in Silver Lake

Kendrick Lamar’s gripping ‘Black Panther’ soundtrack joins a tradition of black movie music

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.