With ‘Dirty Projectors,’ Dave Longstreth lights his own path

Can an album look inward and out at the same time? Dave Longstreth thinks so, and he’s just made one that proves it.

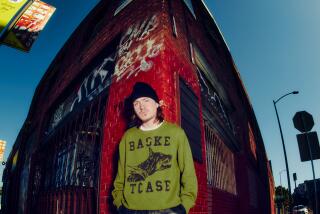

The singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist at the core of Dirty Projectors, Longstreth is known to indie-rock fans for his knotty compositions and high-flown concepts.

In 2009 the group, then based in Brooklyn, N.Y., broke out with “Stillness Is the Move,” an underground hit blending West African-style guitar, an elastic R&B groove and lyrics inspired by dialogue from the Wim Wenders film “Wings of Desire.” Before that came a so-called “glitch opera” about manifest destiny and a freewheeling re-creation of “Damaged” by the caustic punk band Black Flag.

Longstreth, now based in Los Angeles, took a more introspective approach for Dirty Projectors’ new self-titled effort, which charts in detail his painful breakup with a former member of the band, singer Amber Coffman.

“I don’t know why you abandoned me / You were my soul and my partner,” he sings to open the album in “Keep Your Name.” In fact, he knows exactly why, as he makes clear when he runs down all the ways he disappointed his ex: “I wasn’t there for you / I didn’t pay attention / I didn’t take you seriously / And I didn’t listen.”

But if “Dirty Projectors,” due Feb. 24 from Domino Records, is Longstreth’s most personal work, the album is also his most expansive, with a deeply varied sonic palette and a cast of collaborators — including the adventurous R&B singer Dawn Richard and the veteran hip-hop engineer Jimmy Douglass — from well beyond the cloistered indie-rock scene. The result seems to channel Longstreth’s private thoughts even as it reaches toward the pop mainstream he’s encountered recently thanks to his production and songwriting work for Kanye West, Solange and others.

“The longer I’m in the game, the more I realize that the songs I’ve connected with are songs that tell a story — that seem to come from the experience of the writer,” Longstreth, 35, said on a recent afternoon in Hollywood. When he was younger, he added, he had trouble believing that honesty could scale up.

“But in this mass-media era, the idea that exposure is antagonistic to truth-telling — it just doesn’t apply,” he said, tugging on his fuzzy beard. “Look at Kanye: He’s marshaling all these different media and art forms — music, dance, Time magazine, TMZ — to tell a story about who he is on this massive level. It’s fascinating.”

This new notion of Dirty Projectors grew out of a need for change. Longstreth began making music by himself under the name while studying at Yale, but by 2009 the group had become a reliable touring act with regular members including three female vocalists; their darting harmonies distinguished “Bitte Orca” (the album featuring “Stillness Is the Move”) and its 2012 follow-up, “Swing Lo Magellan.”

Longstreth enjoyed that phase of the band, especially the camaraderie that developed between the players on the road. “But it’s a grind,” he said. “And at some point you become aware that this” — he meant playing the same songs onstage night after night — “is different than following your muse.”

So after touring “Swing Lo Magellan” for a couple of years (and ending his relationship with Coffman), Longstreth turned his attention to projects outside Dirty Projectors. He devised a 70-piece orchestral arrangement for Joanna Newsom and produced an album by the acclaimed Tuareg guitarist Bombino.

He also began spending time in L.A., where he met producer Rick Rubin, who introduced him to West. That’s Longstreth humming and playing organ on “FourFiveSeconds,” West’s three-way acoustic jam with Rihanna and Paul McCartney.

“Being a spoke in the wheel of someone else’s process,” as Longstreth put it, helped reenergize his own creativity, and soon he was writing songs again, though not with the most recent version of Dirty Projectors in mind. He’d conceived the group as a “movable feast,” he said, “or an amphibious vehicle: something that would go with me wherever I needed to go musically.”

For this project that meant calling on individual musicians who could help him realize songs that spanned a broad stylistic spectrum, from the squirmy digital pop of “Death Spiral” to the brass-heavy “Up in Hudson” to “Little Bubble,” a plaintive folk-soul ballad in which Longstreth reminisces about quiet moments he used to share with Coffman.

Richard, who appears on the reggae-inflected “Cool Your Heart,” said Longstreth encouraged an air of experimentation in the studio. “He gave people space to try things,” she said. But he was also deliberate in “trying to create his own lane,” Richard added. “These songs were built with such elegance and poise.”

Indeed, for all its variety — and its occasional weirdness, as in “Work Together,” with Longstreth’s vocals pitched up to an unnaturally high register — “Dirty Projectors” puts across a remarkable self-assurance; it’s slick and muscular even at its most vulnerable, thanks in part to a painstaking mix by Douglass, who’s perhaps best known for his work with the producer Timbaland.

But the confidence is also baked into the music — in the unembarrassed falsetto Longstreth uses in “Little Bubble” and the way he details his failings as a boyfriend in “Up in Hudson.” Fear doesn’t drive this kind of public confession.

You can see it too in the handful of glossy music videos he’s released for songs from the album. Where Longstreth used to lurk in the background of his own band, now he’s front and center, his face an unavoidable visual presence.

Peter Berard, an executive at Domino, thinks Longstreth is up to the task of carrying Dirty Projectors largely by himself. And he said the videos are one means of attracting young, visually oriented fans who may not be familiar with the band’s earlier work but know Longstreth’s high-profile collaborators.

“Dave is a proven maker of songs that have the ability to travel in the modern world,” Berard said.

Which doesn’t mean that Longstreth won’t have to do some actual traveling to get his album heard. He plans to tour behind “Dirty Projectors,” but because he made it while consciously disregarding the limitations of a live band, he’s not yet sure what the shows will look like.

Asked if that excites him, he said, “Yeah — and it scares me as well.” Then the headstrong seeker laughed. “I’m like, ‘Uh, how am I going to do this?’”

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

How Beyoncé won the Grammys without taking the big awards

‘I ain’t got no love’: Why Donald Trump’s musical choices matter

Lady Gaga’s Super Bowl show was only as political as you wanted it to be

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.