When you take a nice Muslim boy from Baghdad to Coachella

reporting from INDIO — Ice Cube yelled obscenities from the stage. Drunken, shirtless dudes were cavorting in the beer gardens. Young women roamed the fields in various stages of undress.

Had I made a huge mistake bringing Abdullah to Coachella?

Born in Iraq, Abdullah Al-Rifaie is my cousin’s son and the first of my extended Shiite family to make it to America since the fall of Baghdad in 2003. During the mass exodus of millions of Iraqis that followed, he and his family fled to Amman, Jordan, where they now live.

After years of waiting, my cousin finally got her firstborn son into the U.S. on a student visa; Abdullah arrived in Los Angeles in January. At 18, my nephew had never been to a concert before arriving here, never even seen the inside of a nightclub.

Now he was in the middle of the one of the biggest rock and electronic dance music festivals in North America.

“Don’t worry, I’m fine,” he yelled when I shouted, “Are You OK?” for the third or fourth time over the thumping club beats emanating from the Yuma tent. “It’s just like I thought it would be — except bigger and better.”

It’s just like I thought it would be -- except bigger and better.

— Abdullah Al-Rifaie

I’m not sure what I thought would happen when Abdullah pushed into his first crowd at Coachella, stood in front of his first stage ... that he’d suddenly rip off his shirt and run naked into the desert, never to be seen again, or just fall to the ground catatonic with sensory overload.

Certainly the experience was a far cry from life back in Amman, where watching dancing waters at the mall is as close to a public music event as many teens get. Coachella is a two-weekend behemoth of blockbuster performers, flashing LED screens and Kardashian sightings. Even at its humble inception in 1999 as a small, alternative music festival it likely would have blown his mind.

But Abdullah is, improbably to the point of miraculously, a Guns N’ Roses fan. One of his first requests was to see a rock concert, and who better to bring him than his music journalist auntie. Since Guns N’ Roses had reunited and were headlining Coachella, I thought maybe. Then I came to my senses: “Absolutely not!”

It’s two weekends of drinking, pool parties and all-night raves in the desert that many American parents want their kids to avoid.

The Times’ Lorraine Ali chronicles her weekend with nephew Abdullah Al-Rifaie, an 18-year-old Iraqi Muslim and first-time Coachella goer.

When I cover Coachella or an event like it, I fear the excess as much as any of the more conservative Alis in my family, though for very different reasons. As a former music critic I have to actively work to protect my love of music from the inevitable commercialism, bacchanal of merchandising and need to continually up the tweetable outrageousness. That decidedly American brand of pop culture excess can corrupt what’s at the heart of any art form — passion, freedom of expression, mistakes that push things forward — regardless of where you’re from.

Yet here we were, 24 hours in, dancing to Disclosure and having a good time. A surprisingly good time, actually.

It turns out, when you take a nice Muslim boy from Baghdad to Coachella, you remember why these kinds of events began in the first place. “C’mon,” Abdullah pleaded, “let’s ride the Ferris wheel.”

“Guns N’ Roses?! Coachella?!,” he said when I asked him if he wanted to go. “Wow. Yes I can go. This for me is a dream!”

Abdullah made a playlist for our ride out to Indio from Los Angeles, and despite electronic dance music being the genre that defines his generation, his choices were also almost all heavy rock bands from decades ago: Black Sabbath, Metallica, Pink Floyd.

It turns out, when you take a nice Muslim boy from Baghdad to Coachella, you remember why these kinds of events began in the first place.

As his phone streamed “El Sexorcism” by White Zombie, I asked him where he discovered all this stuff since it’s not exactly Top 10 fare back in Amman. “I learned a lot of these songs playing ‘Guitar Hero 1,’”he said. “I played it over and over until I got really good at it.”

By the time we reached the wind turbines outside Palm Springs, we were both belting out the Guns N’ Roses rendition of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” at the top of our lungs. It reminded me of a 1970s summer vacation in Baghdad when his mom and I sung ABBA tunes together in the sweltering hot courtyard.

I was born as raised in Los Angeles, far from my extended Iraqi family. My father was the only one of his bloodline to immigrate to America pre-Saddam Hussein. While my 35 first cousins were raised in Baghdad eating halal meals and praying five times a day, my sisters and I were in the San Fernando Valley eating bacon-wrapped everything and listening to Van Halen cassettes on loop.

Though I was surprised at my initial desire to “protect” Abdullah from Coachella’s insanity, when I thought about it, it made sense. He represents a culture and faith in which I was never fully immersed, but even after a lifetime of living a modern version of Islam, of endlessly explaining such a thing in an increasingly divisive era, I still find my ancestors sitting on my shoulders, expecting something more Arab or Muslim from me beyond a penchant for hummus or the occasional mumbling of “InshaAllah.”

“What is a draft beer?” Abdullah asked as we checked into our hotel before the festival and passed the poolside bar. Coachella daytime parties were in full swing, and, of course, his room had a stellar view of the pool’s cocktail-toting exhibitionism. “It’s something you shouldn’t drink, or your mom will kill me,” I replied. Yes, I was taking him to Coachella, but no, we would not be leaving his faith entirely at the security check.

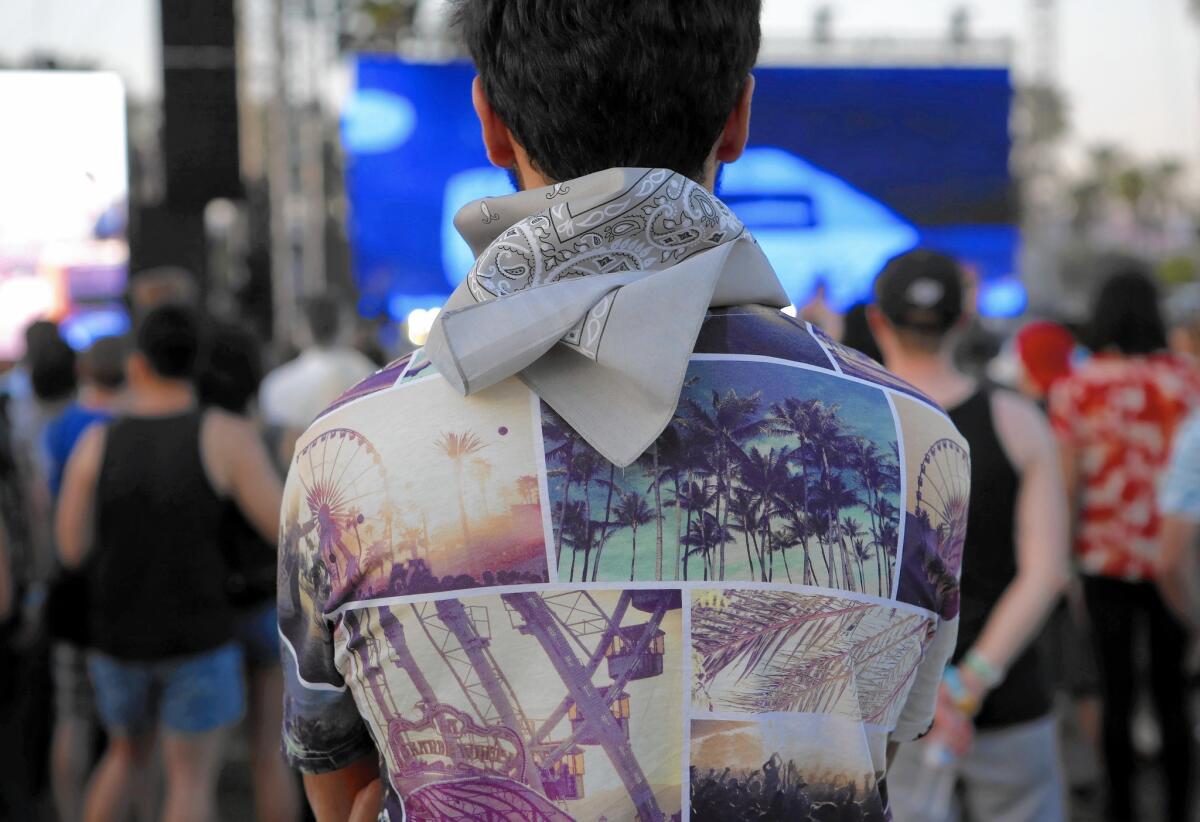

My nephew was easy to spot in the crowd of hipster hopefuls. He was the disarmingly uncool guy wearing an “H&M Loves Coachella” brand T-shirt adorned with iconography associated with the fest — the Ferris wheel, the crowds, the nearby Cabazon dinosaurs.

It’s a fashion line guaranteed to spark scorn among Coachella veterans like myself, who mercilessly denounced the commodification of the once-indie-minded festival. “I wanted something special to wear,” he said.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

On Abdullah, the shirt was a physical manifestation of his enthusiasm, and as it turns out, a very effective weapon against my cynicism. For the first time in a long time, I actually looked forward to attending Coachella.

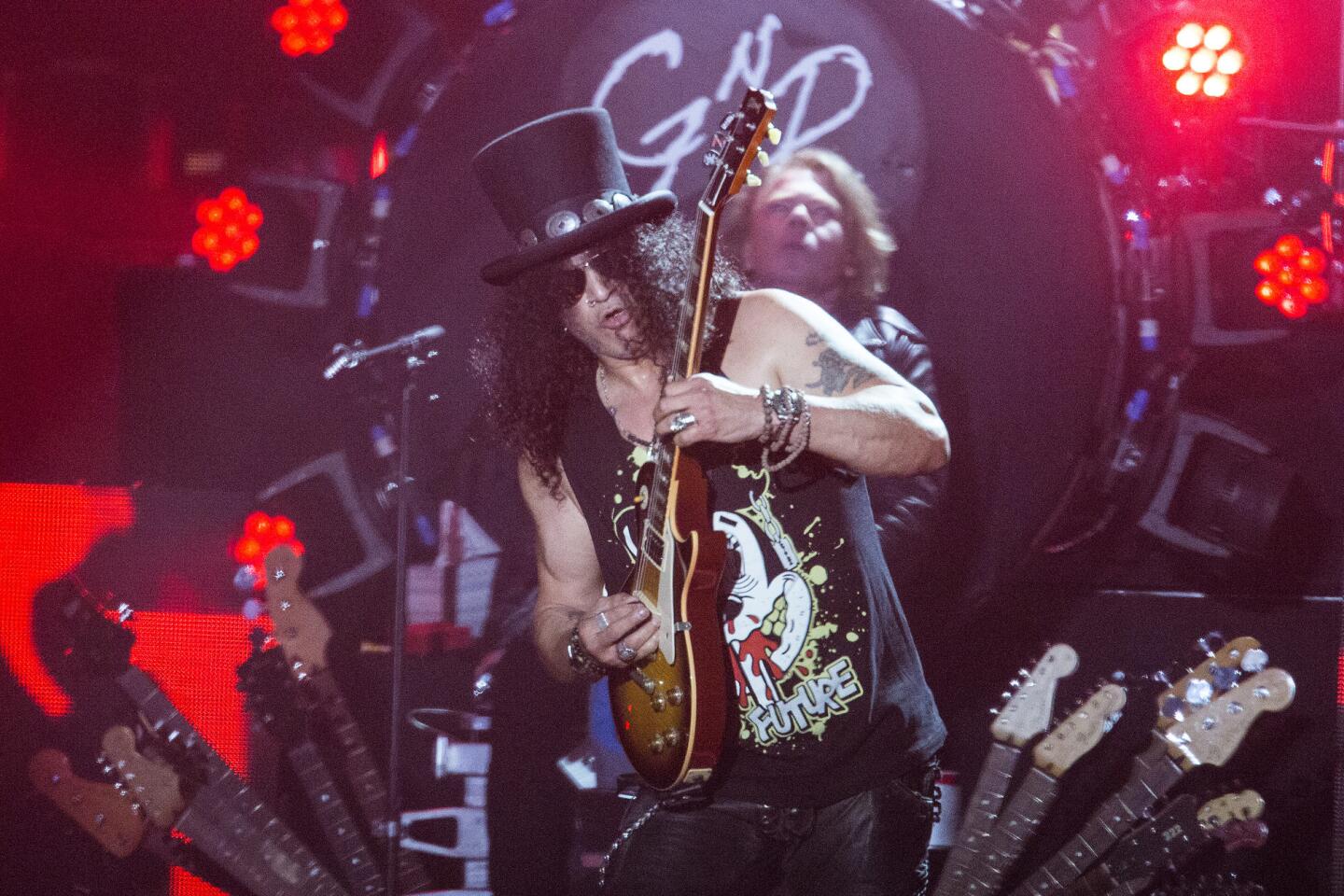

Slash stood before Abdullah on the main stage, playing songs by Guns N’ Roses written a decade before my nephew was born. This wasn’t the animated Slash from “Guitar Hero” but the real thing, top hat, aviator glasses and all. “I think this is historic,” Abdullah said.

Abdullah insisted we do something I never do anymore, and that’s push toward the front of the crowd. Sure, OK, teeth gritted, I did it. Despite the fact that we’d spent eight hours in the sun, he began jumping up and down, singing most every word to every song aloud, playing air drums and taking about a billion pictures on his phone. When his battery ran out, he grabbed mine.

And no, he wasn’t drunk or fresh from making out with some unsavory character who symbolized all that is wrong with kids in 2016 or what religious conservatives of every stripe fear from popular culture. He was lost in the music, driven by the energy, immersed in the very idea of being part of something bigger than himself, something that seemed impossible six months ago.

He was lost in the music, driven by the energy, immersed in the very idea of being part of something bigger than himself, something that seemed impossible six months ago.

When Guns N’ Roses launched into “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” my usual cranky critic stance of refusing to do anything the performer asks (“Throw your hands in the air!” No, I’m folding them) had melted away. I was swaying and singing alongside Abdullah. I had forgotten that miraculous sense of independence and community that a concert evokes, the rush of rebelliousness and connection.

As we walked to the car that Saturday night, bandannas around our heads to keep out the desert dust, we joked that he might be mistaken for a member of ISIS … except in an “H&M Loves Coachella” T-shirt.

“Thank you for all this,” he said through the muffling folds of his bandanna.

I thanked him too.

Twitter: @LorraineAli

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.