Cultural Divide: How Alabama rapper Rubberband OG navigates racism and violence on his hometown streets

Reporting from Montgomery, Alabama — The leaves were yellow and plum, the clouds thin in the sky, when Cortez Oates, known as the rapper Rubberband OG, walked amid suspended rusted steel blocks carved with the names of those who came before. Malcolm Wright. Lynched. 07/09/1949. Chickasaw County, Mississippi. The names went on and on, leading Oates deeper into America’s violent legacy of racism, shunting aside the sun in memory of the broken, battered and burned.

Light as a whisper, scrawled in tattoos, Oates, whose songs bristle with guns, medallions and money, stopped beneath a row of blocks. They hung from an open-air roof as if the stilled feet of dead men. He stood in the quiet, on this hill above Montgomery, once busy with slave traders and the clatter of chains, and said: “Nothing’s changed. The Ku Klux Klan wore white bed sheets, and now they’re wearing police uniforms.”

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice lists the names of more than 4,000 African American men, women and children lynched between 1877 and 1950. Unfolding over six acres, the memorial, which opened in late April, is a sparse and powerful architecture of reckoning, a hushed yet blistering cry against the nation’s most grievous sins. It is not far from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s house and the bus stop where Rosa Parks waited in defiance.

Rubberband OG knew inklings of this past. But growing up with hustlers, crack dealers and cops, who every Tuesday and Thursday raided the Tulane Court housing project, he had different concerns, like scraping up a dollar or two and heading to Church’s Chicken on the corner to buy a leg or a thigh. The other day, Rubberband OG, 27, who drives a white Escalade and is one of the South’s rising rappers, passed his old neighborhood. It was rebuilt and prettier, but still Section 8.

He stopped a couple of hundred yards away at the small, white clapboard home of King, now a museum beyond a magnolia tree on Jackson Street.

“Never went inside,” he said.

“Not in the whole time you were growing up?”

“We had other things on our mind,” he said. “Beating the system. Watching for police. We were broke, looking out for ourselves. But looking at it now means a lot.”

The legacy of Malcolm Wright, the perseverance and eloquence of King and the hectic, musical life of Rubberband OG play in eerie reverie on these streets. In a time of Black Lives Matter, police shootings of men of color, emboldened white supremacists and a president who incites cultural divisions, racism in America is subtle and glaring, written in history books and exclaimed tweets, shaping immigration policies, university admissions and how a man like Rubberband OG navigates a world beyond the bounds of his beat patterns and lyrics.

The lives of African Americans resonated through film and art in 2018, notably Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman,” Barry Jenkins’ adaptation of James Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk,” Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Prize and Michelle Obama’s best-selling memoir, “Becoming.” The era of Jim Crow’s systemic racism is long gone, but there are disturbing imbalances. Blacks make up about 13% of the U.S population, but account for roughly 40% of the incarcerated population, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. The median household income in Montgomery, a predominantly black city, was $46,545 in 2017, or more than $10,000 below the national median.

“With all the civil rights history in this city, you’d think things would have changed more,” said Jroc Bell, who grew up with Rubberband OG and is now one of his posse. “But we’re still struggling. You can’t find a job that pays $15 an hour. Back when we were growing up, if your friend got killed, you cried and got over it. Rubberband is speaking to what’s really happening. The poverty and hustling. The shootings and drug selling that’s going on not just in Montgomery but all over the world.”

Rubberband OG settled into the front seat and drove on, every corner raising a memory, like lightning scattering sparrows. Getti. Booger. Rachat. The names hit the air like verse. Two cousins and one friend gunned down in recent years.

Rubberband OG is accustomed to gunfire and funeral hymns. He was shot at in a recent drive-by, blurring and ducking while doing a Facebook livestream. Many of his songs, including “Bout That Life” and “2019 (Freestyle),” are rife with guns, flaunted money, misogyny and young men of vengeance. They don’t glorify violence so much as lay bare the starkness of lives caught in a sequestered world of cruel codes and unforgiving pecking orders. They snap and swagger but beneath their staccato loops are echoes of desperation. The lyrics startle in their venom.

“If he runs shoot him in the back. . .eat him like a snack.”

“I want see the [man’s] mama cry.”

It’s true and it’s him, but it’s not all of him.

“Every positive song I do gets overlooked,” he said. “So I rap about what they want to hear, and what they want to hear is the violence and stuff like that. It reflects reality. Most times these songs get played in a club, and when you’re in a club you’re drinking and feeling good. So you want to hear stuff about money because you bought yourself something good to wear for that night. You feel like money when you got your little outfit on. The violence, I don’t know it’s crazy. It’s what we see.”

Rubberband OG wrote “Keep Your Head Up” as homage to his single mother, who worked three jobs after his father disappeared when he was 4. The soon-to-be-released song “Why Lord?” examines the deaths of his cousins and friend, tying existential questions to faith and loss. His voice softens when he talks about these songs. The hard edge of him, the one in videos draped in jewelry and brandishing weapons, loses its sharpness and he appears as if a man looking for answers to things big and small: “My grandmother is deaf. I never heard her talk. What would she sound like?”

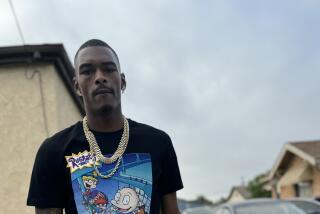

He can seem at one with the air, tapered jeans, wrapped in a winter coat, his mother’s name, Kathy, blooming on his neck. Rubberband is a nickname for how he held his money; OG, less the slang “original gangster,” in him means old soul or something close to it, the way his spirit resides in a moment, how he glides through a crowd.

His friends say he composes all the time — he must have 300 songs written down or waiting like angels and bad men in his head. He started when he was 9, etching rivers of words in school books. His mom bought him a beat machine when he was 12. The world takes shape when he writes, its colors and darkness, its ways of escape. Inspired as a boy by Tupac, and later by Gucci Mane and Young Jeezy, he wants to be as big as Jay-Z.

“OG speaks the truth,” said Martez Ligon, another member of the posse. “He was born to tell it.”

He dropped out of school in the 11th grade. He smoked weed and kept close to his eastside crew. He later found a job making headrests at a Hyundai factory, but lost it when he didn’t show up one day, a fact that still bothers him. He liked the work and felt he was unfairly let go. With a savings of $1,300, he made his first hit, “Go Crazy,” catching the attention of DJs and Think It’s A Game Records. The boys of his youth have grown into men with him. They often hang out at Ligon’s house, playing video games, talking shows, forking food from a skillet.

“I started seeing myself on YouTube and thought this could work,” said Rubberband OG, who has performed across the South. “But now that I have a name, people I don’t know might want to injure me. I’m on videos with money, jewelry, and now people I don’t know don’t like me either. I like to stay gone. Away from the city. People outside the city treat you better than the city where you’re from.”

The Bible and prison are full of men cast out from their homes. They hold too harsh a mirror, make a place see its demons. Rubberband OG quit going to church a while ago, but he still prays. His mother taught him. He is at once a twist of poetry and an unsettling statistic. He’s the kind of young man conservatives hold up to signify what’s morally wrong with society. He has four children — a 9-year-old son, a 2-year-old daughter and two 1-year-old daughters — from four women. He is not married.

“It wasn’t the right thing to do,” he said. “I was living fast, but that’s all changed.”

He stayed quiet. Listened to traffic. Moved on.

“If you’re a black man and aren’t going to college or into the NBA, NFL or rap, it’s like: What else you going to do?” he said. “You’re scared to unbuckle your seat belt because a cop thinks you’re reaching for a gun.” In his song, “If Something Happen,” he imagines his death, divvying up cars and money, leaving love and other things to his mom and kids, and taking away the belief that, “I’m still gonna be a legend in the hood.”

DJ Solo, a sage of Montgomery’s music world, who recently mixed The Eagles’ “Hotel California” with Chris Brown’s “Deuces,” said Rubberband OG embodies the rawness of Southern hip-hop. “He’s bringing a conscientiousness to street life,” Solo said. “He’s saying, ‘I went through it so you don’t have to.’ He’s authentic. His brain is fast. His albums are like stories.”

Solo sat before a few computer screens; his voice sounded like one you hear on the radio at 2 a.m., telling you about Miles Davis or Charlie Parker. Smooth, a little smoky. The room across the hall was stacked with vinyl and turntables. He recalled the music from back in the day, the time of black-and-white TV, fire hoses and police dogs; the era when Martin Luther King Jr. ended his march from Selma below the steps of the state capitol in Montgomery, where a statue of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, still stands.

“I don’t think enough musicians today are bringing awareness to what used to be,” he said. “They’re not showing our history here. History is becoming memory. It shouldn’t. I hate that you have to remember where you came from.”

The ticket-takers and guards at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice knew Rubberband OG. They smiled and nodded. He stepped through the metal detector and into the history DJ Solo talked about, the past that when you see it, like the sculpture of a man in chains, makes you think it’s alive. Skin cut, dignity unbroken, the man in chains stared at Rubberband OG. He stared back. Centuries fell away. Wind blew across the autumn grass, fading, until the air carried no sound. He walked on through rows of blocks — more than 800 Corten steel monuments — etched with names.

They subsumed him.

“Look at this,” said Torrey Davone, a DJ and Rubberband OG’s manager.

Henry Smith, 17, was lynched in Paris, Texas, in 1893 before a mob of 10,000 people.

“Ten thousand people,” Davone said. “It’s like they thought it was entertainment. You can’t understand the magnitude of it until you stand here.”

The monuments were suspended, some low, some high. Davone and Rubberband OG seemed lost among them, the kind of encompassing loss a man must have felt being bound and led to a tree by a crowd with a rope.

“Racism is still here,” said Davone. “It’s politics and power now.” They walked on. Read. “Caleb Gadly was lynched in Bowling Green, Kentucky, in 1894 for walking behind the wife of his white employer.”

Sun slanted across the monuments, brightness mixed with shadows. Rubberband OG stayed quiet. A man so quick with rhymes and the spin of syllables, he wondered how to fit words to such a thing.

This story is the fourth in a series of occasional articles by Jeffrey Fleishman about cultural touchstones reflecting the tumultuous political times across America. The other pieces in the series include:

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.