Oscars: Why Neil Patrick Harris (and everyone else) is wrong for the job

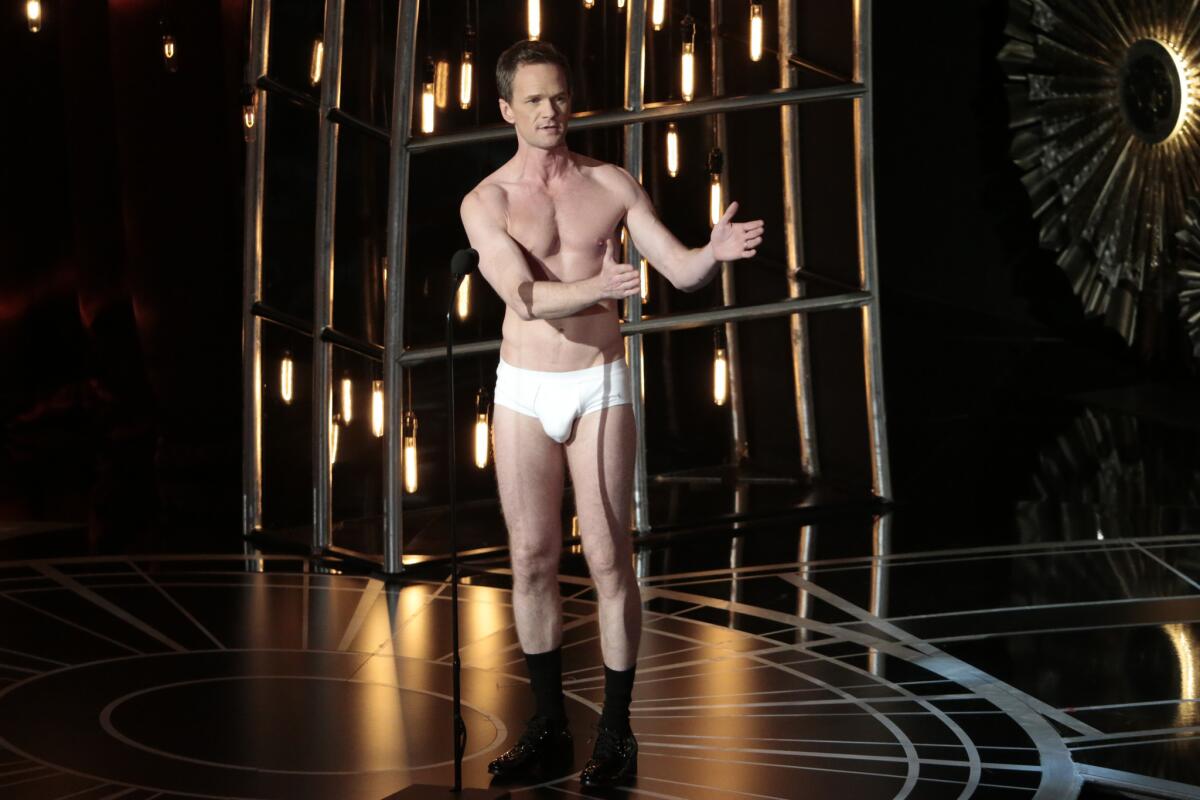

Neil Patrick Harris’ uneven performance at the Oscars on Sunday (“bombing … atrophied ... airless,” and those were some of the kinder assessments) raised the question that comes up nearly every late winter, as the endless circuit of judging the year’s best movies finally reaches a merciful end.

Will the host manage the high expectations, competing interests and tricky tasks placed in front of him?

Is there someone, in other words, who can beat the Dolby Theatre odds? Or is the Oscar-hosting hex such that, like logic in a Michael Bay movie, it defeats anyone who would try to conquer it?

Certainly the recent track record isn’t encouraging. An attempt by the show to go older and more traditional, with Billy Crystal in 2012, felt staid and retrograde, a misguided quest for past glory. An effort the following year to be more forward-thinking, with Seth MacFarlane, ran into issues of inclusiveness and good taste. Another modern effort to be more forward-thinking, with Anne Hathaway and James Franco, ran into issues of comedy and wakefulness.

Ellen DeGeneres’ 2014 performance was better, in spots, but it’s easy to forget in the haze of Harris hand-wringing all the tedium and awkwardness in her show too — the constant references to Twitter, the pausing of a telecast for 10 minutes to attend to a pizza delivery.

This is the current state of Oscar hosting. We criticize the current emcee unremittingly, offering up the cold comfort that “last year was better.” Then, when the next installment rolls around, we repeat the line, forgetting how bad the previous year really was. Oscar hosts are an endless cycle of false nostalgia and defining quality down, a syndrome also known as the “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise.

One telling detail is that the most memorable event of the past five years (or 18 hours of telecast time) is a moment that the motion picture academy, given its druthers, would rather not have had and couldn’t plan for anyway: John Travolta’s mangling of Idina Menzel’s name. Not that this stopped producers from taking another run at it this year, 12 months after we’d all made every conceivable quip about it on Twitter. Producers brought Travolta and Menzel out for some forced stage patter, in a bit that landed with all the currency and freshness of a Nixon joke.

With so much disappointment, it’s not surprising that the best Oscar host is the one who’s never had the gig. He or she comes with all the promise of what we like about them from other venues, without any of the bad feeling about what they’ve done in this one.

Until this weekend, that person was, of course, Harris himself. After electrifying turns emceeing the Emmys and Tonys — I’ve been in the room for a few of his latter gigs, and there isn’t a modern performer who compares — he was seen as Oscar’s great savior, the one who could make everything better if only producers gave him a chance. Well, now that’s all over, and the bouncing ball of high hopes will land on someone else. Already cries can be heard for Jimmy Kimmel. If he’s smart he’ll look to Harris and realize there are some excruciatingly painful activities that are nonetheless preferable to crossing this job off his bucket list, such as, for example, re-watching “The Bucket List.”

There’s a sense with the host gig that one simply can’t win, and whatever personality producers go with (and whatever tonal tack that personality takes), Oscar viewers will come away wanting something else.

That’s in part because the show is an innately unmanageable beast, like trying to subdue a horse and ride it at the same time. The host’s assignment is to guide us skillfully through the packed and schizophrenic proceedings while also not trying too hard to overtake them, which is ultimately like asking someone to try very hard and not try at all.

Some of these problems are fixable. On Sunday a few of the most egregious moments were not of the inherent sort but the result of specific choices made by Harris, many seemingly in the moment. After the filmmaker behind one of the Oscar-winning shorts revealed heartbreakingly that her son had taken his own life, Harris, either not listening or not caring, took the microphone back and made a joke about her dress. That tone-deafness was repeated when, after a charged political moment in which the Edward Snowden film “CitizenFour” won the documentary Oscar, Harris could manage only a “for some treason” joke. It would have been bad enough if it was just a weak pun; it was made a lot worse because it seemed to take a political stand, and a controversial one at that. It was Barney Stinson without the charm.

More hands-on producing, or even a return appearance, might beat out some of those habits. Yet many of the challenges simply come with the territory. I heard a few people critique that Harris was not funny enough to pull off the gig, and that what the Oscars needed was a true stand-up comic. It sounds reasonable. But the talents of those types tend to be a mismatch for the fragile room and a large mainstream TV audience, and if you have any doubts you can just call Chris Rock or Jon Stewart, who have a special island bunker ready for that moment in the summer when Oscar producers begin calling out to potential hosts.

There’s also been some talk about promoting Golden Globes hosts Tina Fey and Amy Poehler (evidence of their talent is front of mind this week amid the sendoff for Poehler’s “Parks and Recreation”; like Fey, she’s at the top of her game). Yet such hopes labor under a similar misapprehension. The duo’s act works at the Globes, with a TV audience half the size and a room twice as drunk. But put them on an Oscars stage and I suspect they’ll run into the same issues Stewart and Rock did, or some new ones yet devised. Not for nothing did Fey hint a few years back that she wouldn’t want the podium. “That gig is so hard,” she said.

No host, it turns out, can crack the essential conundrum: How to meet a cold room that pretends to want to laugh, but really has its feelings easily bruised, like the overconfident guy at a party who tells you to hit him then gets mad when you do. Nor can it decode the audience at home, which these days means the audience on its phones. People on Twitter have a lot more to say if they don’t like what you’re doing than if they do. Which means social media for a massive event like the Oscars has settled into a kind of binary state in which a host is greeted with either heckles or silence. Neither is very conducive to good reviews.

The most obvious solution amid all this is for the Oscars to go host-less. The speeches and presenters are what people remember (and, arguably, are looking for) anyway, and a host can only get in the way. OK, so it didn’t quite work when the academy tried it 26 years ago — “surprisingly devoid of magic,” The Times said in its review. But then, it’s not like the 25 years of hosts since have been Houdini-like.

At any rate, it would probably be best to make a host’s presence as slight as possible — an opening segment (those tend to work, maybe because there’s not yet enough time for our optimism to be crushed by experience), a closing number sending us into the good night and a lot of scarcity in between.

But human ambition is such that it that ignores reality and negates experience. And so there is always another personality waiting in the wings, someone who wants the gig, someone who believes they can beat the odds, someone whose name comes tumbling off our lips the minute the show ends, if only for the reason they’re not the person who just finished hosting.

That’s actually an ideal moment, come to think of it, because all possibilities lie ahead of us and an unrealized future host has yet to make any missteps. Unfortunately, an Oscars doesn’t take place then, dooming us to repeat the cycle of disliking the person we spent so long begging for, then begging for someone new so we can do it all over again.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.