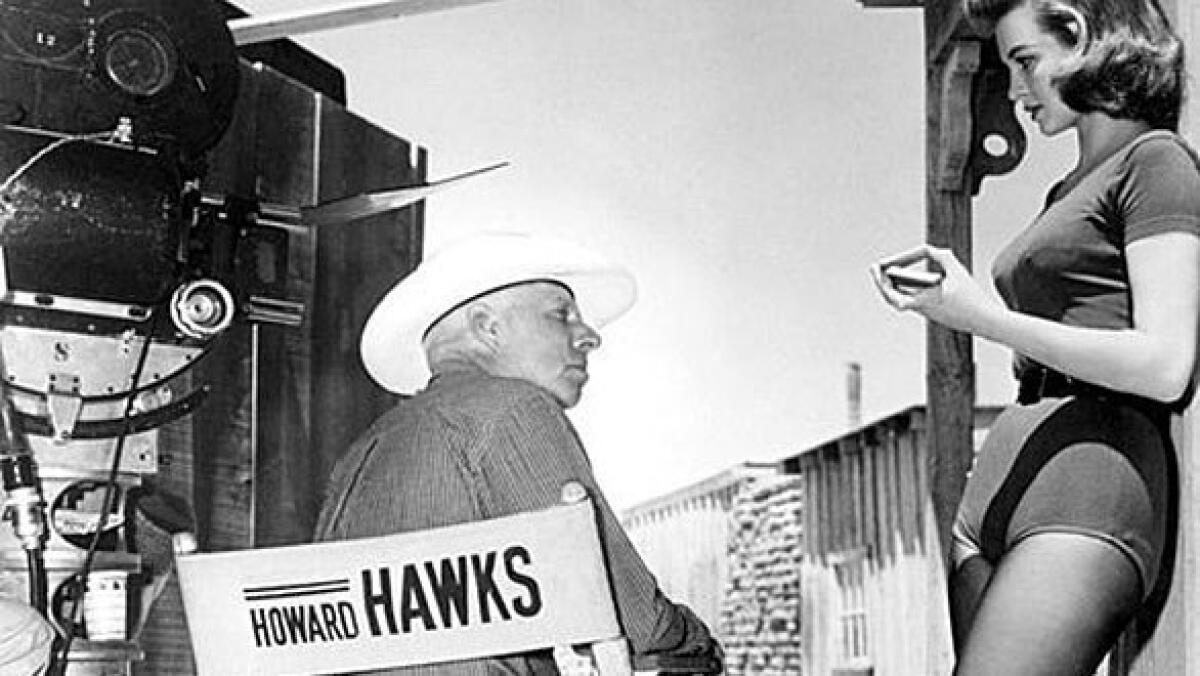

Director Howard Hawks, in focus

Howard Hawks never met a movie genre he couldn’t adapt to splendidly.

In a career that spanned the silent era to 1970, Hawks directed gangster melodrama (1932’s “Scarface”) screwball comedies (1938’s “Bringing Up Baby”), westerns (1948’s “Red River”), film noirs (1946’s “The Big Sleep”), musicals (1953’s “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”) and adventures (1939’s “Only Angels Have Wings”).

This weekend, two of his best comedies, 1940’s “His Girl Friday” with Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell and 1941’s “Ball of Fire” with Gary Cooper and an Oscar-nominated Barbara Stanwyck, screen at the American Cinematheque’s Aero Theatre.

PHOTOS: A trio of Howard Hawks’ leading men

Hawks respected screenwriters, and his films crackled with witty, sophisticated dialogue. He worked with some of the era’s best scribes, including Ben Hecht, Jules Furthman, Billy Wilder, Charles Brackett, Leigh Brackett and Charles Lederer.

“He had certain obsessive themes,” said film historian/professor Joseph McBride, whose acclaimed 1983 book “Hawks on Hawks” has just been reprinted. “It is a very unified body of work because he dwells on the same few themes. His work is not as rich as John Ford or Orson Welles in terms of breadth and range. He had a kind of narrow range but within that, he’s superb.”

Male friendship, McBride said, is a major theme in Hawks’ work. “He often talked about the films as love stories between two men. There are really profound movies about friendship like in ‘Rio Bravo’ with John Wayne helping out the drunken deputy, Dean Martin. Their complicated relationship is very moving.”

Hawks liked “strong women who have to live up to the group ethos. He deals a lot with group cohesion and conflicts. He doesn’t deal with society on a macro-level. He does with it small groups, and they are usually people who are in some dangerous profession.”

Hollywood took Hawks for granted. Some of his films, which are now considered masterpieces, didn’t wow critics at the time. Hawks never won a competitive directing Oscar, earning a sole nomination for directing Gary Cooper to his first lead actor Academy Award in the 1941 biopic “Sergeant York.” Hawks finally earned an honorary Oscar in 1975 for being a “master American filmmaker whose creative efforts hold a distinguished place in world cinema.” He received the honor just two years before his death on Dec. 26, 1977, at age 81.

PHOTOS: Behind-the-scenes Classic Hollywood

Hawks didn’t begin to get his due until the French New Wave directors of the late 1950s discovered his films. Jean-Luc Godard called him the “greatest American artist” and Jacques Rivette added that “Hawks epitomizes the highest qualities of the American cinema; he is the only American director who knows how to draw a moral.”

McBride believes that there were several factors why Hawks didn’t get the respect he deserved until late in his life.

“He didn’t get written about like someone like Frank Capra, who was more aggressive about getting publicity, or an Orson Welles or a John Ford,” McBride said. “Hawks said to me that the studios didn’t want directors to be too well known because they would get too big for their britches and would demand more money and more control.”

Genre filmmakers, he said, were “looked down on for a long time. Now, we really realize how genres can be used for personal expression. “

McBride, who first met Hawks at the Chicago Film Festival in 1970, described the filmmaker as “laconic and witty in a low-key way.”

He also enjoyed life. “He flew airplanes,” McBride said. “He was a fisherman and hunter. He was the archetype of the great director who had a great life outside of film.”

PHOTOS: Holiday movie sneaks 2013

McBride said Hawks “brought out the best in actors” by giving them the freedom to shed their screen inhibitions.

He tapped into Katharine Hepburn’s and Grant’s zany side in “Bringing Up Baby” and showcased Marilyn Monroe’s comedic prowess in one of her first seminal films, 1953’s “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.” He took a chance on a young fashion model named Lauren Bacall and made her a star in her first film, 1944’s “To Have and Have Not,” which starred her future husband, Humphrey Bogart.

Hawks changed the course of Wayne’s career when he cast him in the demanding, complex role of a tyrannical cattle rancher “Red River.”

McBride recalled that Hawks told him that when Ford saw “Red River” he was surprised by the Duke’s level of acting.

“Ford made Wayne a star, but he didn’t totally believe in Wayne’s ability to act until he saw that movie,”

McBride said. “After that, Ford began giving Wayne more interesting parts.”

-------------------------------

‘His Girl Friday’

When: 7:30 p.m. Saturday

‘Ball of Fire’

When: 7:30 p.m. Sunday

Where: American Cinematheque’s Aero Theatre, 1328 Montana Ave., Santa Monica

Admission: $11

Information: https://www.americancinematheque.com

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.