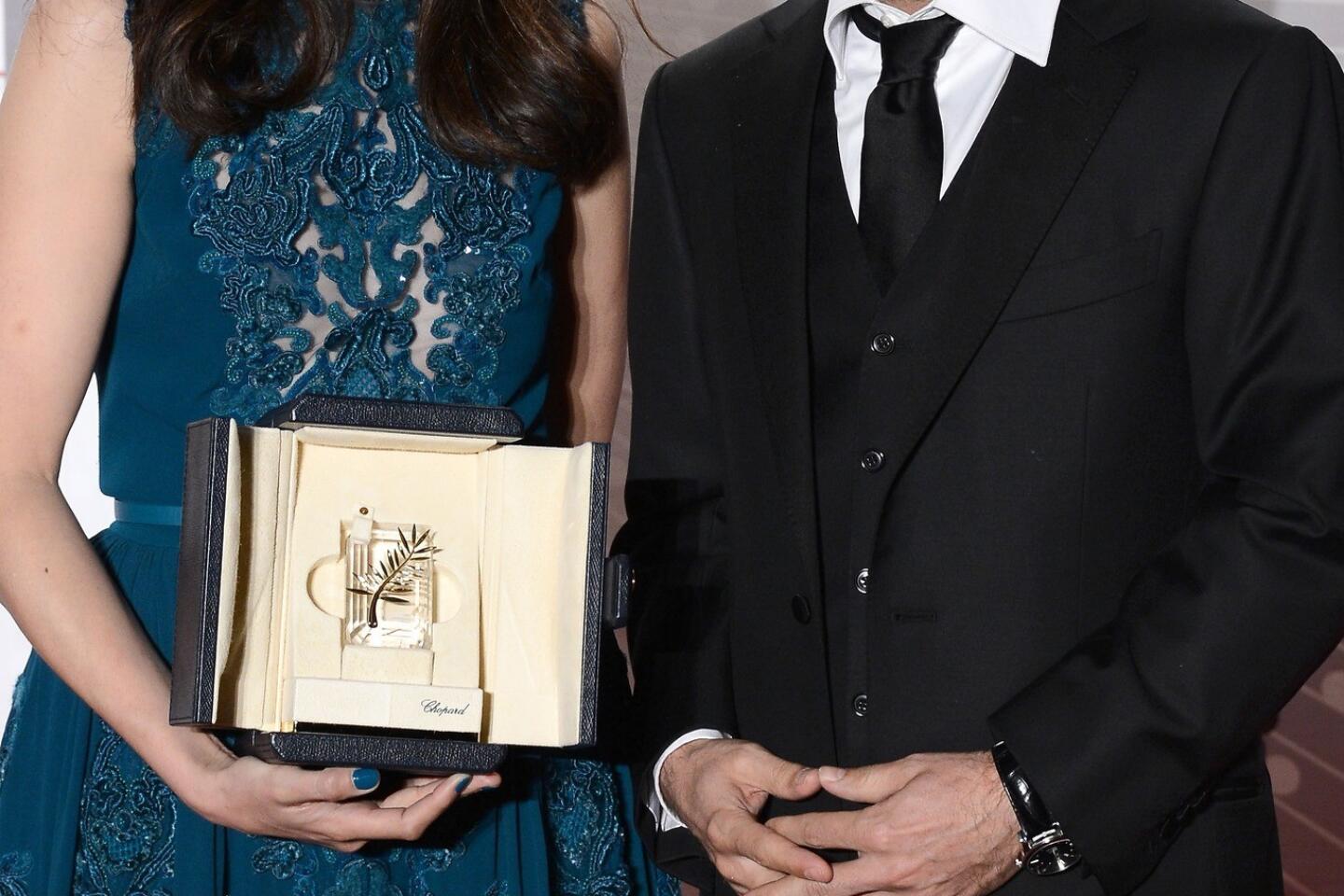

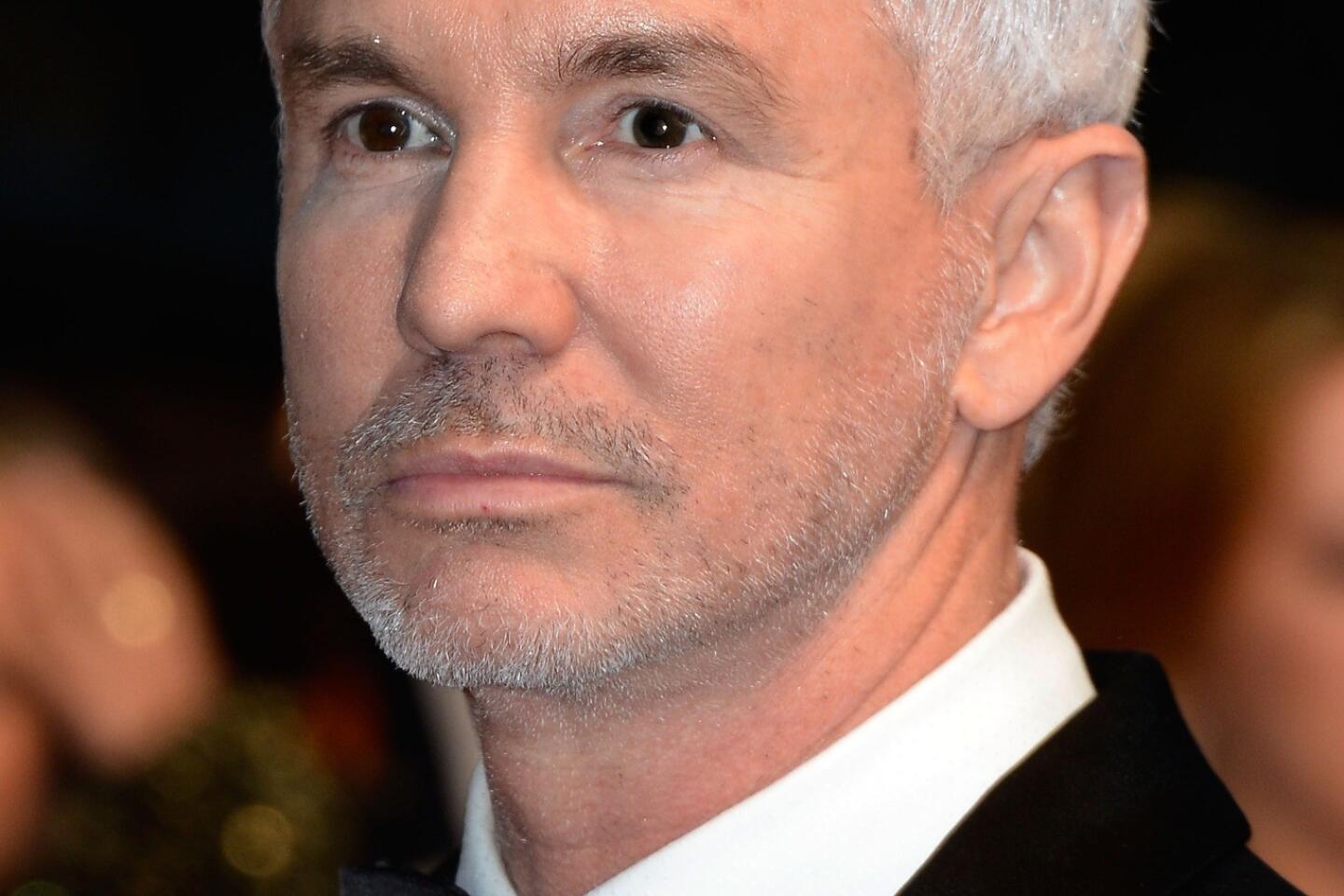

Asghar Farhadi goes for maximum emotional impact in his films

CANNES, France — “Stories come to me,” says Asghar Farhadi, his sharp eyes focused, intense. “This one came to me, and I decided to follow it.”

It sounds straightforward, simple even, but nothing about the filmmaker’s latest work, “The Past,” fits that description.

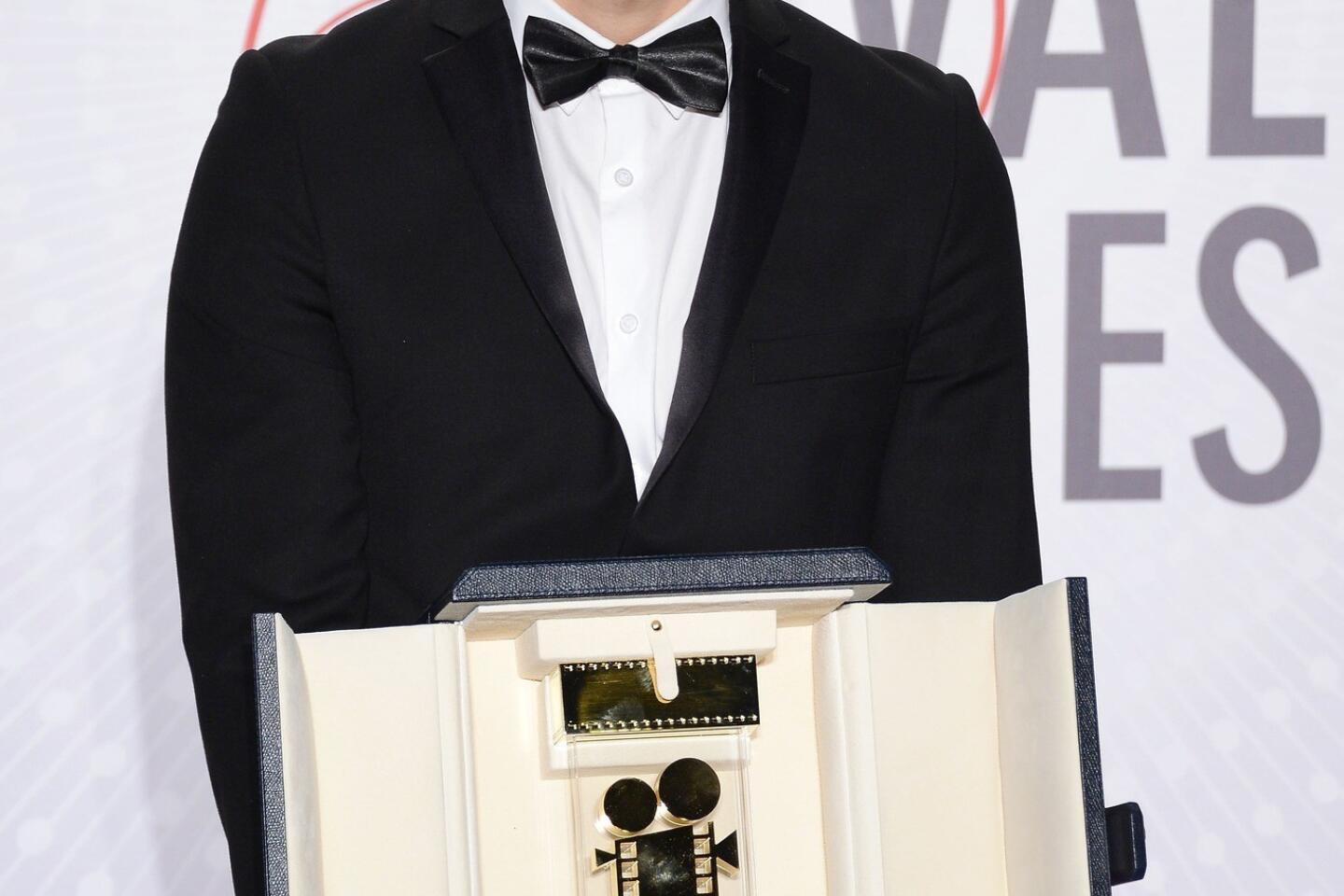

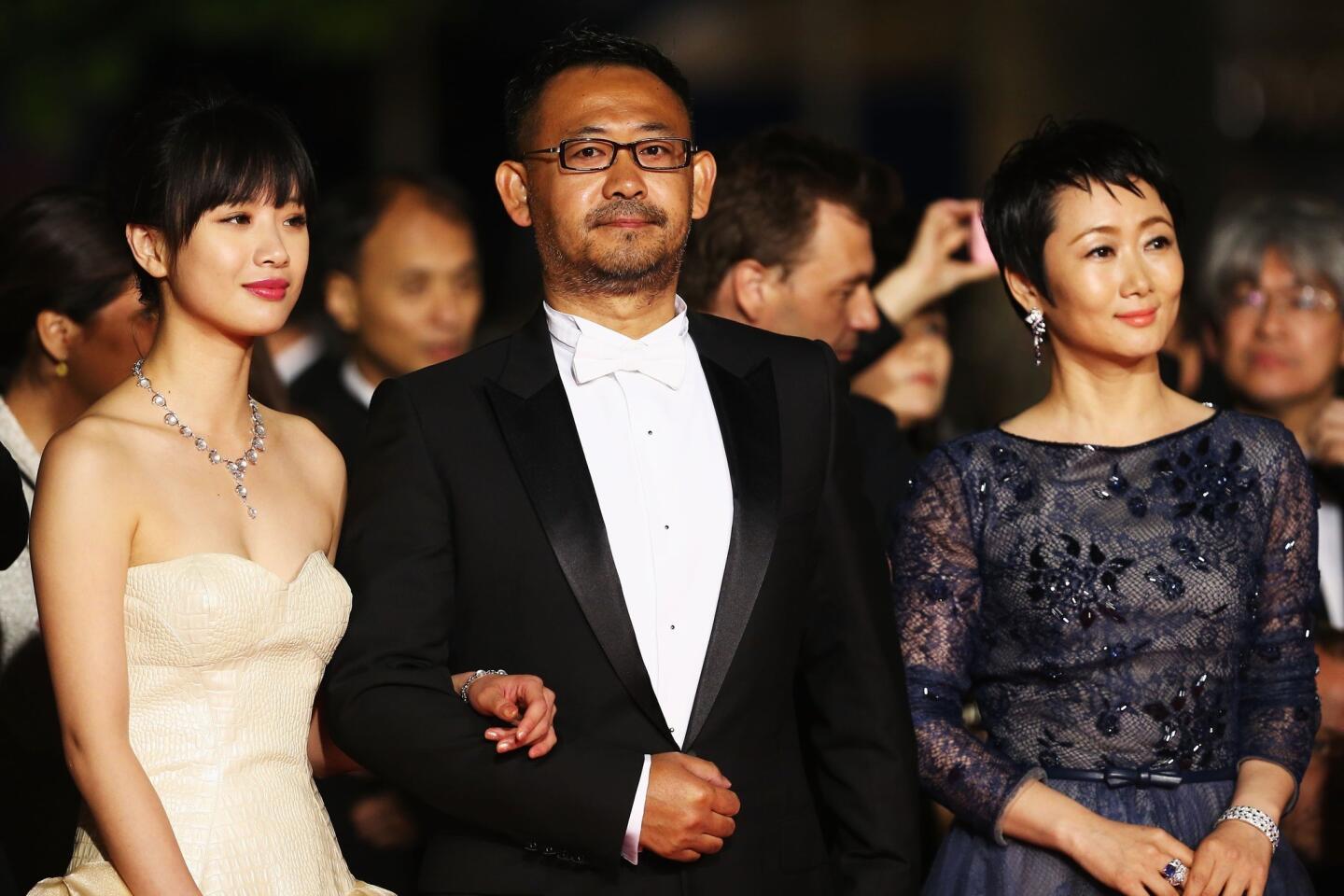

Iranian writer-director Farhadi’s name may not be familiar, but his previous film, 2011’s “A Separation,” certainly is. The picture won more than 70 international awards, including the Oscar for foreign language film; the extent of its global box office success surprised both its creator and its country of origin.

CHEAT SHEET: Cannes Film Festival 2013

“We are used to Iranian films being acclaimed in festivals, but not this kind of popularity,” Farhadi says, speaking in Farsi through a translator after Friday’s screening here. “I was personally surprised because I never look forward to anything, so I won’t be disappointed.”

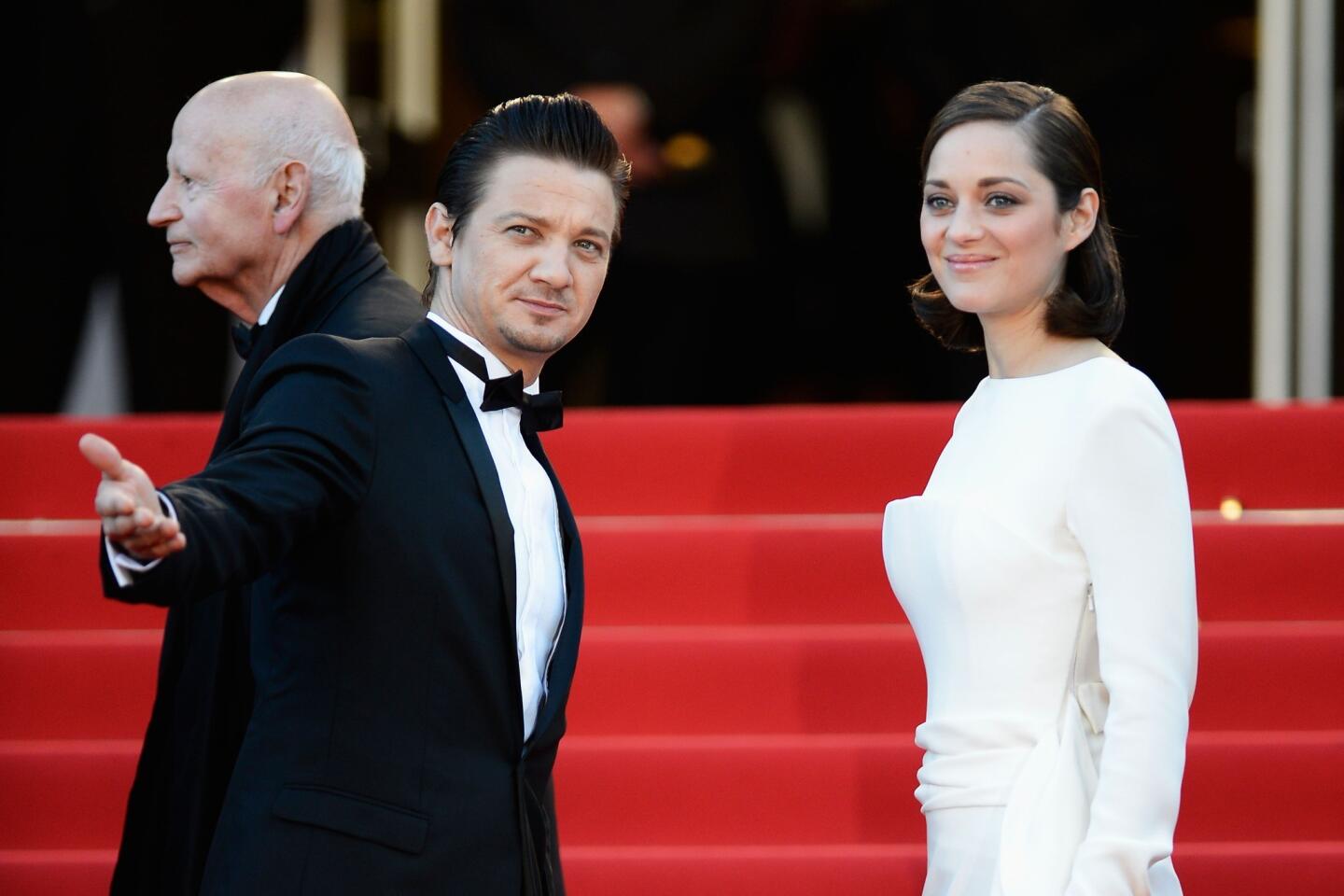

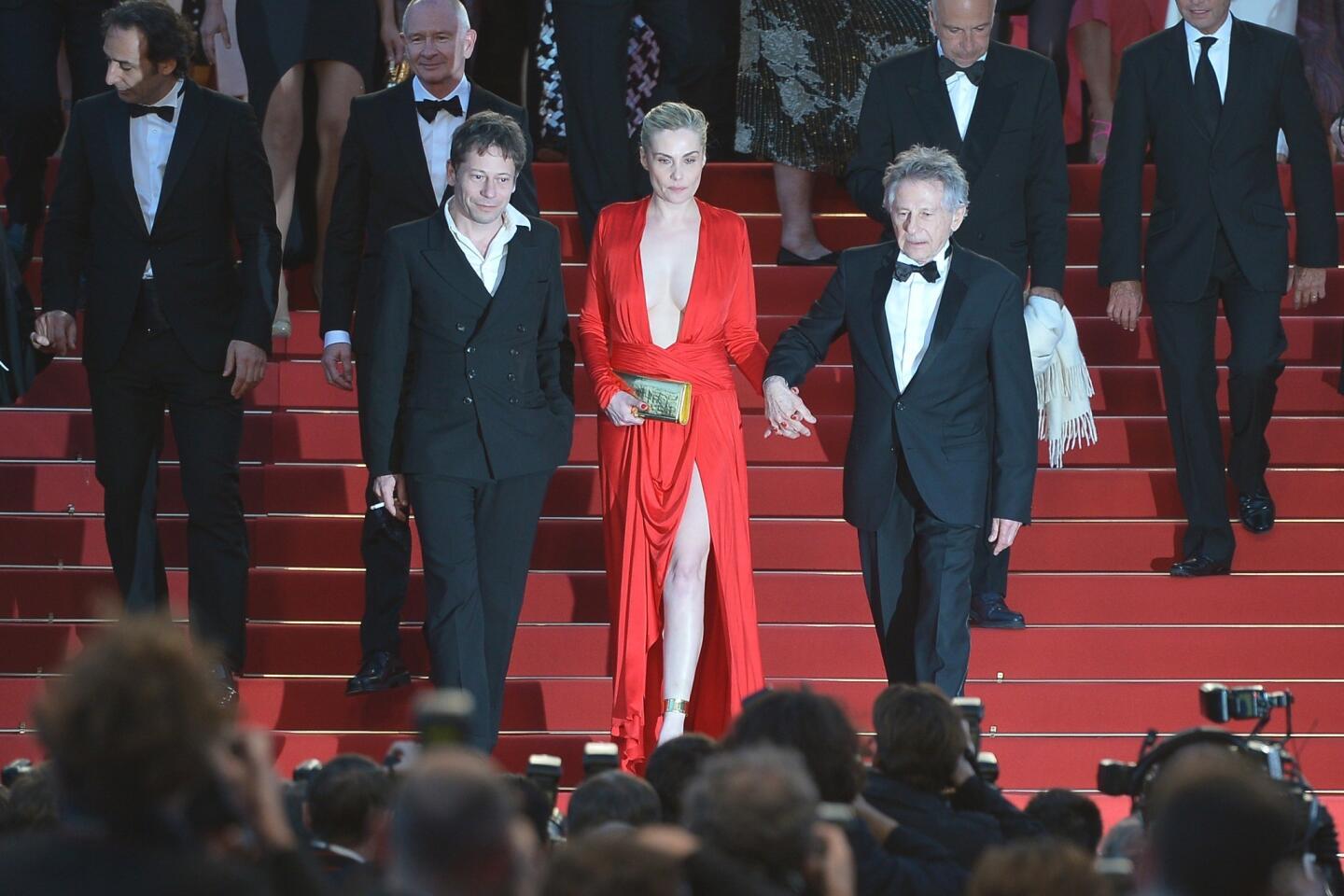

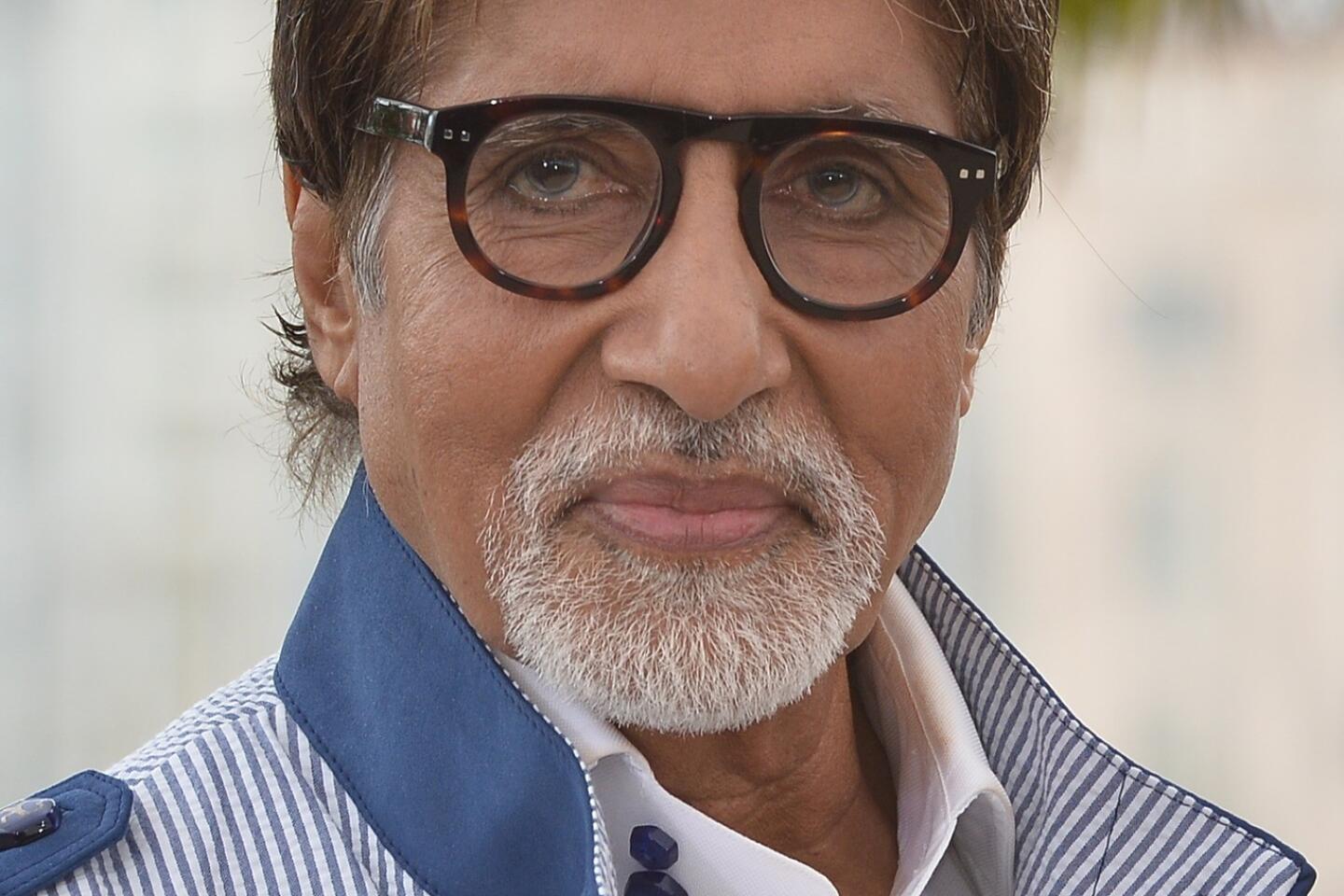

Farhadi hadn’t planned to make his next film outside Iran. Nor had he planned to work with “The Artist’s” Bérénice Bejo, Tahar Rahim of “A Prophet” and top Iranian actor Ali Mosaffa.

But when “The Past’s” story came to him, he went with it. Farhadi decided to make this Paris-based story — an Iranian man returns to France to give his wife the divorce she wants, with devastating consequences — even though he didn’t speak French and had to direct the movie through a translator.

With Bejo as the wife, Mosaffa as the husband and Rahim as the new man in her life, “The Past” shares with “A Separation” a passion for domestic drama and a gift for the realistic depiction of intense emotional situations, the more intense the better, with the family as the center of it all.

“There is nothing more universal than family,” Farhadi says. “You don’t have to explain the context when you work with it; anyone on any part of the Earth can relate.” But for this director, “family is the pretext, the way to talk about society as a whole.”

Society leads to talk about the situation for filmmakers in his homeland, and though Farhadi admits that “filmmakers in Iran are in a different situation from the rest of the world because of the restrictions we undergo,” he is frustrated that Western media focus on that rather than “the struggles filmmakers go through to overcome restrictions. Censorship is not stronger than the potential for creativity.”

On the other hand, the director has no patience with the notion sometimes put forward by censorship advocates back home that “we have good directors because we’ve been creating limits. Restrictions encourage creativity only in the short term. In the long term, they can destroy it.”

Talking with him, and listening to his actors at a Cannes news conference, make it clear that as a filmmaker, Farhadi is nothing if not meticulous. “It’s true about my real life too,” he admits, “and it makes things a bit difficult.

“If I enter a room in which everything is perfect, I see the one tiny spot that is not and I have to fix it. When I’m shooting, I know that when a shot is done it is done forever, so it has to be perfect before I say, ‘Cut.’ I don’t know where this comes from, but I have always been like this.”

This diligence was key in enabling Farhadi to shoot in a language not his own. Having previously lived in France for two years, the director was “used to the melody of the language, and once the script was completed in Farsi, I worked on the adaptation into French for two months. I knew in all cases what word was specifically chosen for what.”

Also helping were Farhadi’s painstaking work methods, which meant for this particular film two months of rehearsals and four months of shooting. “It scares producers,” he admits, “but I have found good ones who accept it.

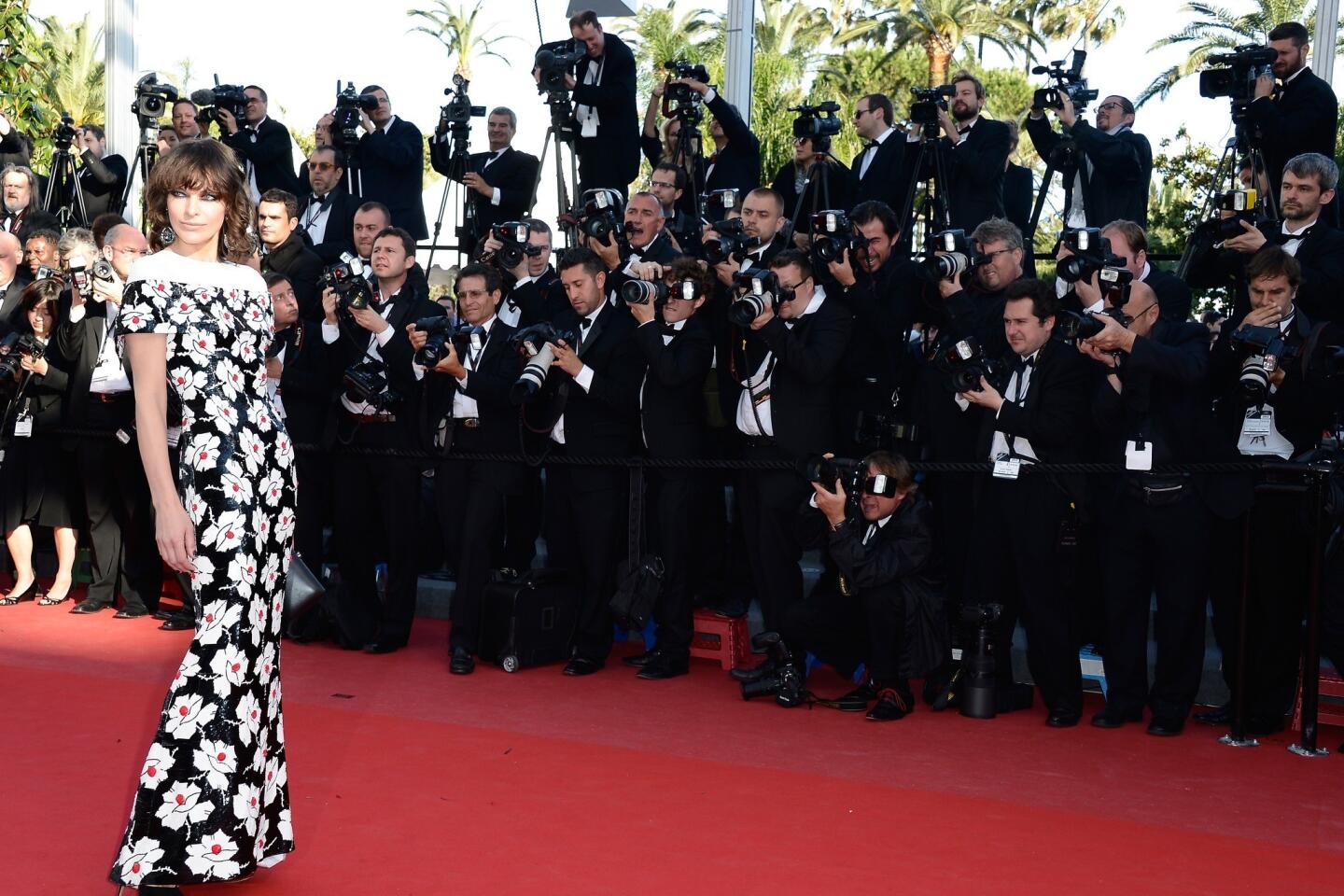

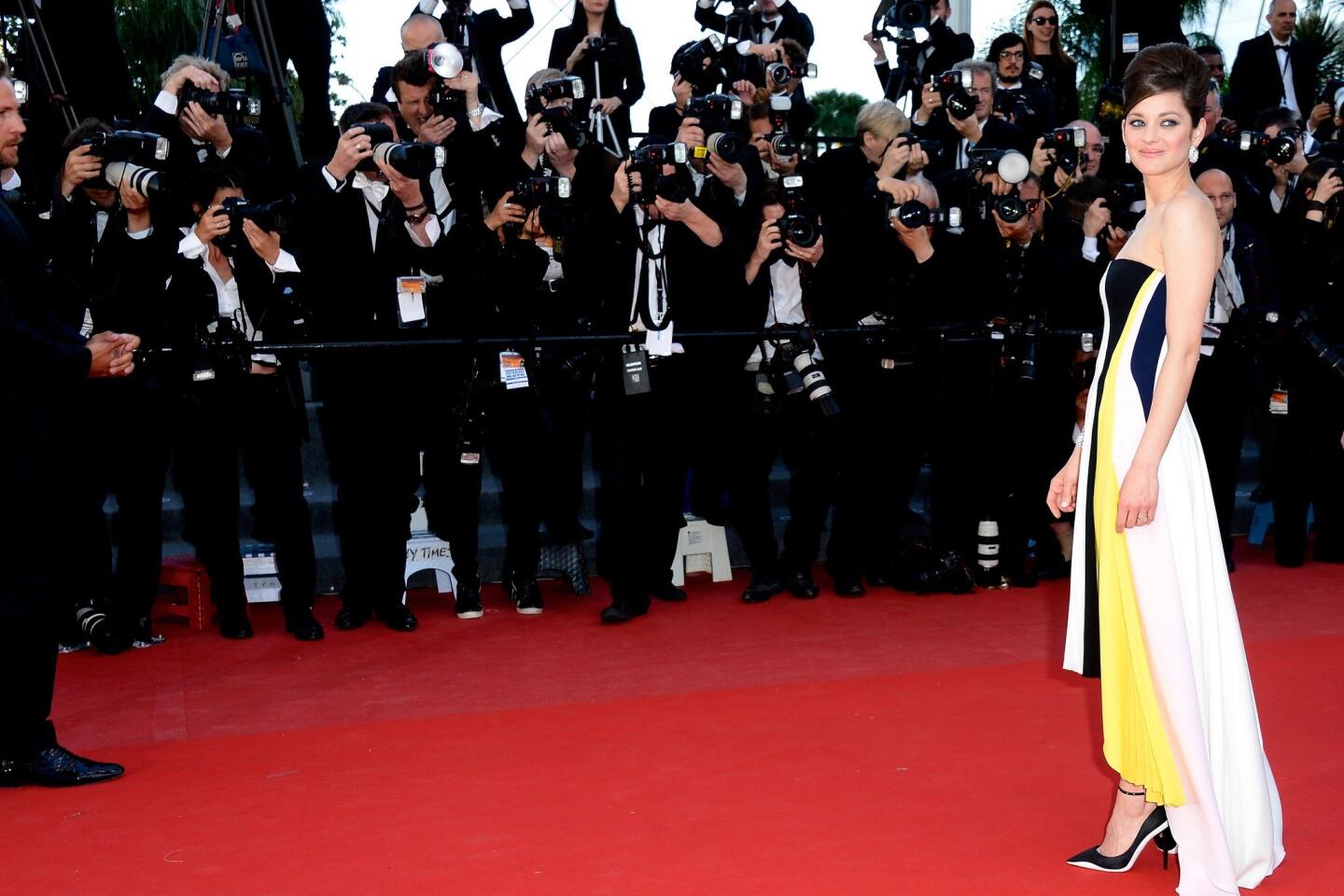

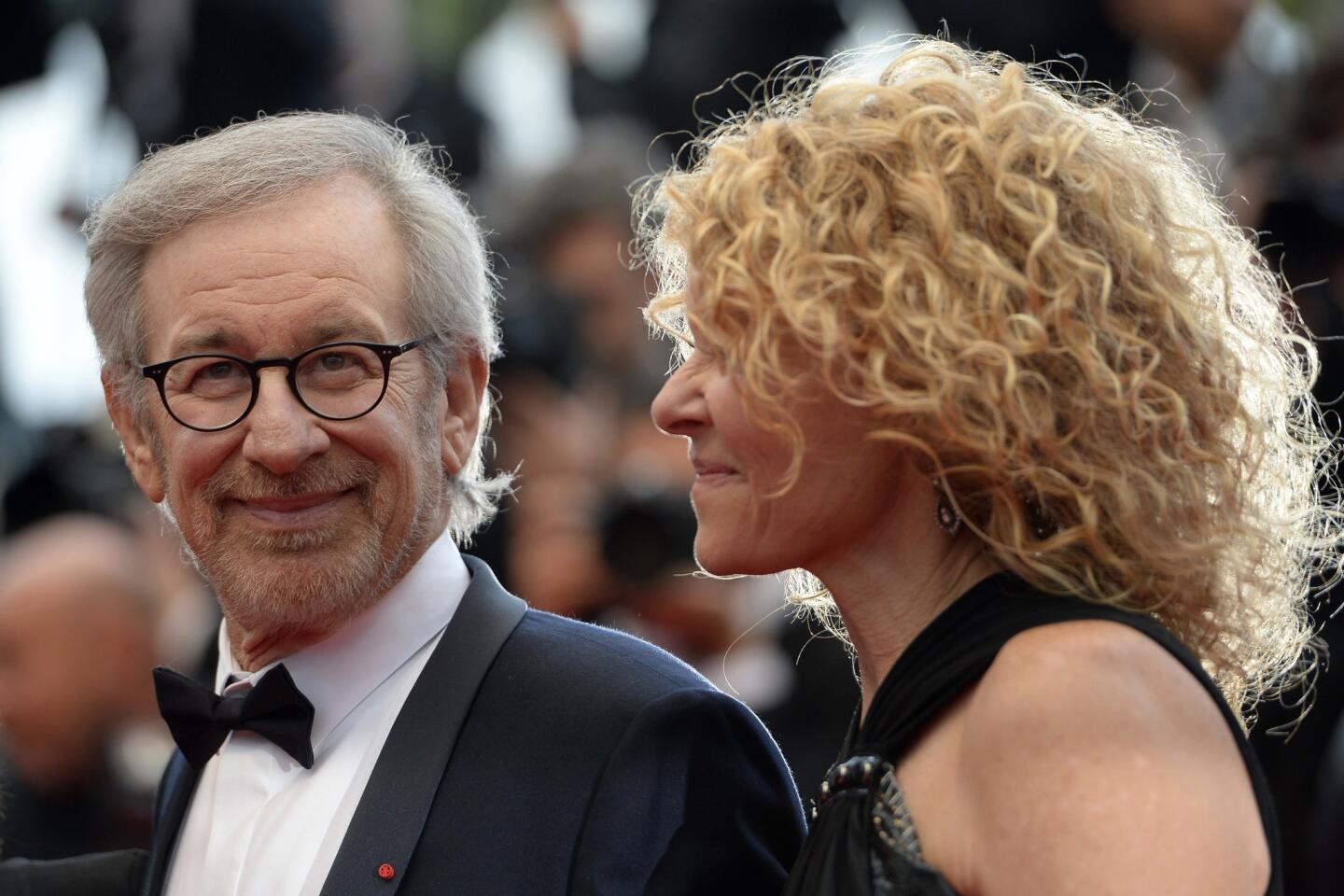

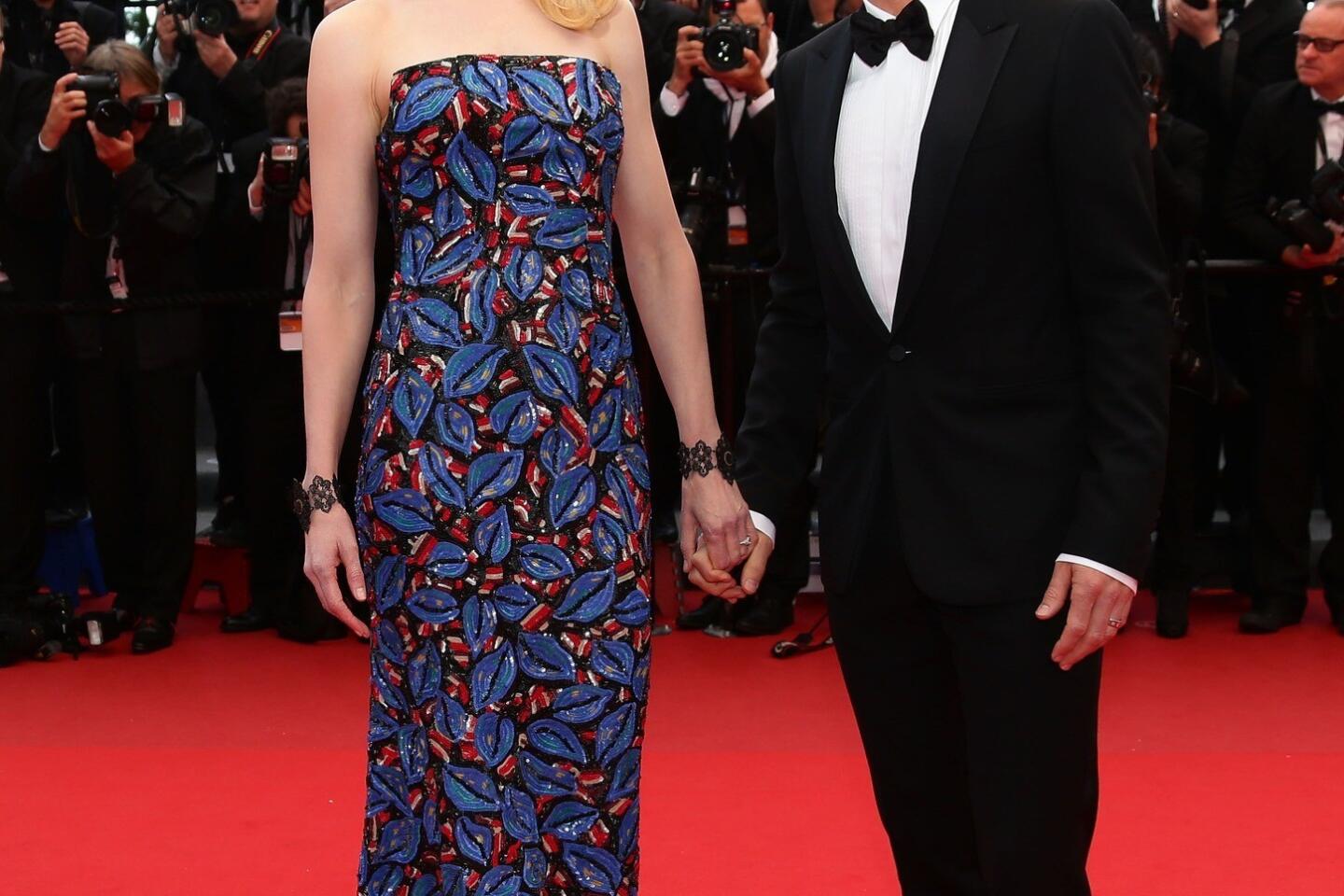

PHOTOS: Cannes Film Festival 2013

“I need the process to go very slowly to make the thing believable both for myself and for the crew. And I want the actors to go through the same journey I had in writing the script. Everything I did as a writer, I accompany them in re-creating through rehearsals, so the actors feel like they have created the character, not the director. My script is ready, but I pretend I don’t have anything.”

Speaking at the film’s news conference Friday, “The Past’s” performers endorsed their director’s methods. “He is extremely precise, nothing is left to chance, but we feel very free in our acting,” said Rahim, while Bejo was even more enthusiastic.

“With so much rehearsal, it was as though we had 50 takes before the first day of shooting, a fabulous luxury,” the actress said. “He decided on all the details. I had nothing left to do but act. It was extraordinary.”

This, then, is the paradox of Farhadi: He has found a way to use strict control to gain maximum emotional impact. “I think cinema has always been too extreme with emotion,” he says. “Films have been either emotionless and cold or a profusion of totally uncontrolled emotions. I wish to be somewhere between these two extremes.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.