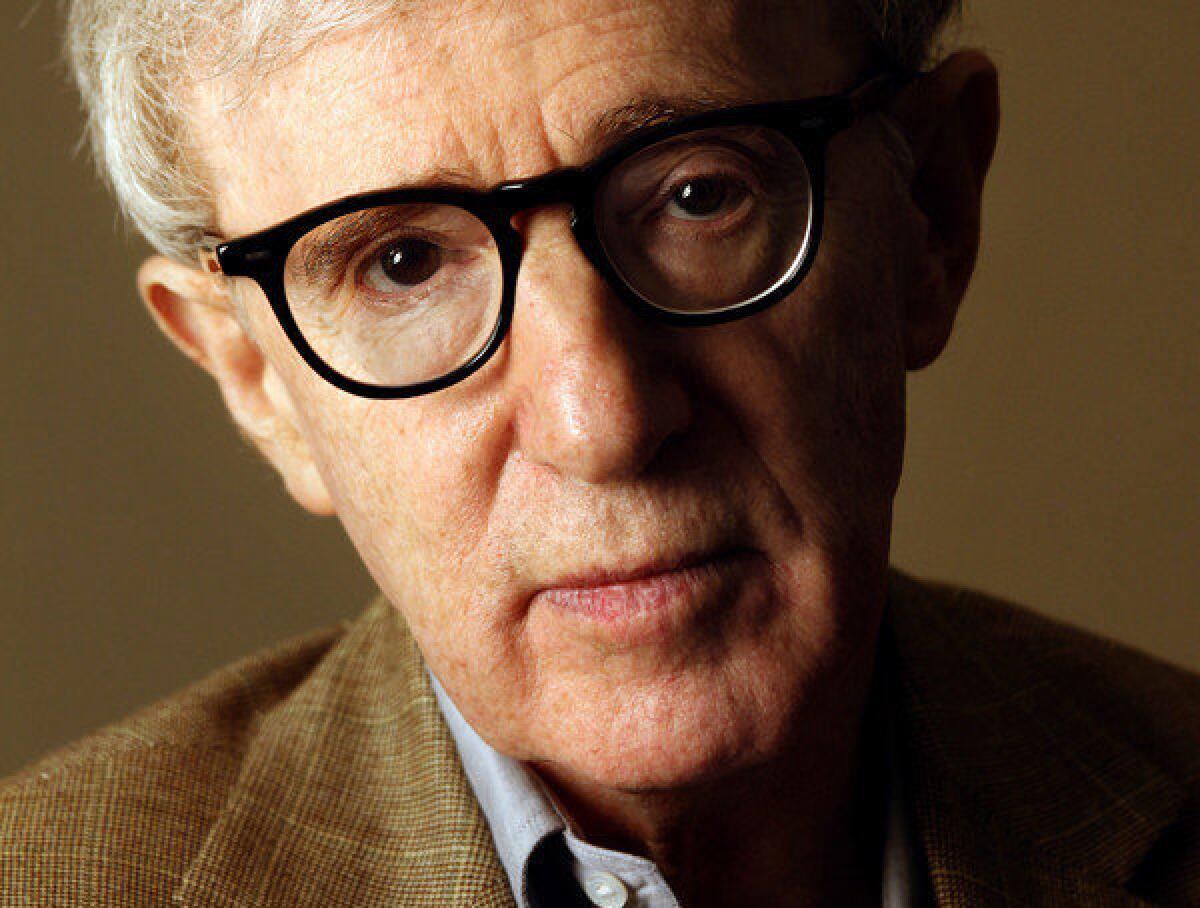

‘Blue Jasmine’: Woody Allen on regrets - He’s had a few

NEW YORK — Does Woody Allen have regrets?

His new film, “Blue Jasmine,” amplifies the air of concentrated self-examination that has long been a hallmark of his work. Though marked by buoyant moments of wry humor, the film is devastating in its intense survey of a life in the free fall of mental and emotional collapse. Cate Blanchett gives a tour-de-force performance as a wealthy New Yorker who discovers that her husband has built their fortune through fraud. After losing everything, she winds up with her decidedly more downscale sister in San Francisco, left to sift through the remains of her life.

Opening July 26, “Blue Jasmine” finds Allen further exploring a thematic conceit that has been percolating through his recent movies since at least the dual stories of 2005’s “Melinda and Melinda,” as in film after film he has been pondering a series of existential what-ifs.

PHOTOS: The many movies of Woody Allen

In 2010’s “You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger,” Josh Brolin played an unhappily married man who became obsessed with what his life would be like with a woman in the apartment across the way. In the 2011 smash hit “Midnight In Paris” — for which Allen won the Oscar for original screenplay, his fourth — Owen Wilson stepped from modern day into the Jazz Age, imagining it as better than his own time. In “To Rome With Love,” Alec Baldwin played a man who seems to meet a younger version of himself in Jesse Eisenberg.

Whether in a comedic or dramatic mode, these films are all structured around a reflective, ruminative mood, as if Allen has been looking back on his celebrated, knotty life and examining the forks in the road.

“I would say, I’ve lived 77 years now, and there have been things in my life that I regret that if I could do over, I would do different,” Allen said in a recent interview that found him in a warm mood on a cold, late-spring afternoon. “Many things that I think with the perspective of having done them and having time that I would do differently. Maybe even choice of profession. Many things.

“But I think if you ask anybody that’s honest about it, there has to be a number of choices they’ve made in their life that they wished they’d made the other choice. They wished they had bought the house or didn’t buy the house, or didn’t marry the girl or did. So I have plenty of regrets. And I never trust people who say, ‘I have no regrets. If I lived my life again, I’d do it exactly the same way.’ I wouldn’t.”

-

Allen has worked for nearly 40 years in a modest suite of rooms on the ground floor of the type of politely upscale Upper East Side apartment building many know only from Woody Allen movies.

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

Off a bustling thoroughfare, past two doormen and down a tastefully appointed hallway, one finds a nondescript door with a small, unremarkable sign. Through that door is a rather cramped anteroom filled with cardboard boxes and a second, slightly shabbier door. Through there is a cluttered workroom with doors leading off in various directions. Somewhere behind there is Woody Allen. He is looking for a cough drop.

It is in this former bridge club that Allen casts his films and edits them, seeing to the unglamorous workaday details of moviemaking. He recalled when he once visited the offices of Martin Scorsese, just a few blocks away, “You would have thought that it was the law firm of Scorsese and John Foster Dulles” by comparison with his own “sleazy little operation.” He is quick to add, “I really don’t need anything more.”

Allen has maintained a startling work rate, making in essence one film a year for going on 35 years. At times it can be frustrating to keep up with his output, and there can be something haphazard about his prolificacy. This may be why “You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger” struggles to make $3 million in the U.S. one year and “Midnight in Paris” brings in nearly $57 million the next.

Allen’s relentless pace, his craftsman’s regularity rob his films of the event feeling a new work by a Scorsese or Spielberg are often met with, as if he is purposefully trying to lower expectations. Films that seem undercooked on first glance gain resonance over time, while other films lose their initial impact. Though never to be counted out entirely, Allen makes it easy to overlook any single film for the ongoing rush. In a way, it can be as if he doesn’t entirely get them all either.

“I don’t know why they like one and not another,” he said of the surprise audience response to “Midnight” compared with his other recent films. “If I could figure it out, I might be able to get rich.”

“Blue Jasmine” is, by Allen’s own speculation, less likely to find such a broad audience due to its serious, dramatic nature. The film’s structure finds Blanchett’s character reflecting upon moments from her past, looking for clues to her own downfall, creating a deep emotional resonance. She gives in some sense two performances, one as the fine society lady and the other as someone at moments akin to a babbling street crazy in a Chanel jacket.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

The film also has Allen’s typical deep bench of supporting performers, with strong turns by Baldwin, Sally Hawkins, Peter Sarsgaard, Bobby Cannavale, Louis C.K. and Andrew Dice Clay. No character is quite as they first seem, some revealing themselves to be deeper and more emotionally sensitive while others turn out shallow and self-serving.

The in-built joke of casting the rough-hewn Clay in a heady Woody Allen film, and in a pivotal, dramatic role no less, was certainly not lost on the actor. Clay recalled that when his manager first let him know Allen had reached out, his response was, “Woody Allen’s calling for me? That’s the last guy I ever thought would call for me. I thought it was like an April Fool’s joke.”

The film will likely draw comparisons to the story of Ruth Madoff, wife of disgraced financier Bernard Madoff. Though Allen downplays the connection, Blanchett did do some research into their story, as well as other society doyens deposed by the economic collapse.

“I followed that story in the paper like everyone else, but it was not an influence in any way on the movie,” Allen said of the Madoff story, while noting that he was inspired by something his wife, Soon-Yi Previn, told him of a high-society woman who had to take a job after losing her wealth.

Perhaps what drew him to the idea was an opportunity to look at the all-too-human weakness for self-delusion, the ways in which we all often have to convince ourselves of lies big and small to make it through the day and press on with our lives.

Though the two never did have a conversation regarding the big ideas of the film, Blanchett picked up a clue from an off-the-cuff comment by Allen.

On the phone from Sydney, Australia, where she has been appearing onstage in Jean Genet’s “The Maids,” Blanchett recalled, “He wouldn’t even remember saying it, but he said something along the lines of, ‘We all know the same truth, and that our lives consist of how we choose to distort it.’”

Allen prefers not to think of his work as some sort of veiled autobiography or a series of extended notes on the human condition. Perhaps belying his roots as a teenage joke-writer and early work as a nightclub comedian, he sees his goals as far more modest.

“I’m thinking of entertaining,” he says of what motivates his writing. “That I feel is my first obligation. Then, if you can also say something, make a statement or elucidate a character or create emotions in people where they’re sad or laughing, that’s all extra. But to make a social point or a psychological point without being entertaining is homework. That’s lecturing.”

PHOTOS: The many movies of Woody Allen

While his recent films have seen him traipsing across Europe, shooting in London, Barcelona, Paris and Rome – and he has just begun production on a film in the South of France – Allen saw “Blue Jasmine” as a distinctly American story. New York was an obvious location for a film touching on a financial scandal, but his choice of San Francisco as the film’s second location, home to the character of Blanchett’s sister played by Hawkins, came down to where he thought he could spend a comfortable summer.

“Her sister could have lived anyplace and it would have been fine. I couldn’t live anyplace, that was the problem,” he said.

Allen is notoriously hands-off as a director, with apocryphal stories of his meeting performers for only a few minutes during casting and then barely speaking to them during production. Yet having directed six Oscar-winning performances, he must be doing something right. As far as his leading lady, he said, “I mean, she’s Cate Blanchett, what can you do? You hire her and get out of the way.”

Though he is prone to referencing old-guard art house stalwarts such as Bergman, Fellini or Kurosawa, Blanchett compares him to filmmakers she has worked with such as David Fincher, Jim Jarmusch, Wes Anderson or Steven Soderbergh, framing him as a contemporary working filmmaker in a way his legend often precludes. Since Blanchett and Allen had never worked together, part of her preparation was to speak with other actors who had worked with him and to study the 2011 “American Masters” documentary on him.

“Frankly, I thought he thought I was awful for the bulk of the film,” Blanchett admitted, noting that for her the breakthrough came when she realized it wasn’t her, it was him.

“Once you realize that Woody is never pleased, he is never satisfied, that’s why he makes a film a year, that’s why he’s so prolific as a filmmaker,” she said. “You realize he is actually in some exquisite agony and it’s horrific for him often to hear what he’s written. It’s as much to do with himself as the actors and once you don’t take that personally, I really relished the frankness.”

-

Allen acknowledged one unintended consequence of his prolific output is that his films almost exist in some way outside of his control. Likening the process to a series of sessions of psychoanalysis, he said, unconsciously recurrent themes emerge over years of work.

With its structure that teeters between the problems of the past and the struggles of the present, “Blue Jasmine” grapples directly with the twined difficulties of looking back and moving forward, and how we can all become an unreliable narrator to ourselves.

“I think I was always reflective,” he noted, “I think that may have been a strength and a weakness. Early on, going as far back as ‘Annie Hall,’ there are all these cerebral characters talking about life, thinking about death, thinking about the meaning of life, thinking about why relationships didn’t work, always thinking and verbalizing their thoughts, always reflecting.

“I think I’m no more reflective now,” he added with a slight giggle, “at death’s door. But you do get conscious of it. But I was conscious of aging at 14.”

So if he could go back, by the way, what other profession might he have chosen?

“I might have been happier if I was a novelist,” he replied. “So instead of having to raise millions of dollars to put on these stories, the novelist sits at home; you write, if you don’t like it you throw it away. If I throw something away, I’m throwing away $100,000 every time I take a scene out. So that might have been a better thing. Or music might have been a better thing.”

He seemed to be opening up now, genuinely taking stock of his life and career and looking down roads not taken.

“If I really can go back, early, early, early in my life” — and here he clasped his hands together and pulled them back as the windup to one final curveball — “maybe a ballet dancer.”

Woody Allen — perhaps joking, perhaps not — exists, you might say, at the very intersection of the two, a playful showman amid uncompromising self-examination. As supporting evidence for either case, he added, “I was a very athletic kid.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.