Review: ‘The Act of Killing’ re-creates Indonesian slaughters

“The Act of Killing” takes more than a little getting used to. It’s a mind-bending film, devastating and disorienting, that disturbs us in ways we’re not used to being disturbed, raising questions about the nature of documentary, the persistence of evil, and the intertwined ways movies function in our culture and in our minds.

Director Joshua Oppenheimer accurately calls this film “a documentary of the imagination,” and its unusual form and style meant he worked on it for nearly eight years without any guarantee that it would turn out well. Yet the results are so impressive and unsettling that documentary masters Errol Morris and Werner Herzog both signed on as executive producers.

“The Act of Killing” demonstrates its singular nature right from the start, when it juxtaposes a chilling historical quote with a gaudy, surreal visual tableaux so wildly unexpected it would seem to come not just from another film but an entirely different universe.

The quote, from the French philosopher Voltaire, neatly encapsulates the film’s theme: “It is forbidden to kill and therefore all murderers are punished. Unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets.”

This statement is followed by an image that is pure dreamscape, an inexplicable fusion of David Lynch and an Esther Williams musical. Out of the mouth of an enormous metal goldfish the size of an airplane fuselage comes a line of dancing women glamorously costumed in red and white. Joined by a man garbed in black and a hefty cross-dresser in a floor-length turquoise gown, they make their way to a waterfall while an unseen voice encourages them to experience “real joy.” What could possibly be going on here?

The complex answer starts with the knowledge, conveyed by type on screen, that back in 1965 the Indonesian government was overthrown in a military coup. The threat of a communist takeover was given as the reason, and within a year more than 1 million putative communists were executed by the new regime, though the reality was that anyone the regime didn’t like could be so labeled and eliminated.

PHOTOS: Billion-dollar movie club

Though Gen. Suharto, the leader of the coup, was forced to resign in 1998, his people remain in power in Indonesia. American documentarian Oppenheimer, who wanted to make a film about the situation, found that while the families of the victims were still too traumatized to speak, the killers themselves had been turned into national heroes and were delighted to boast about what they had done.

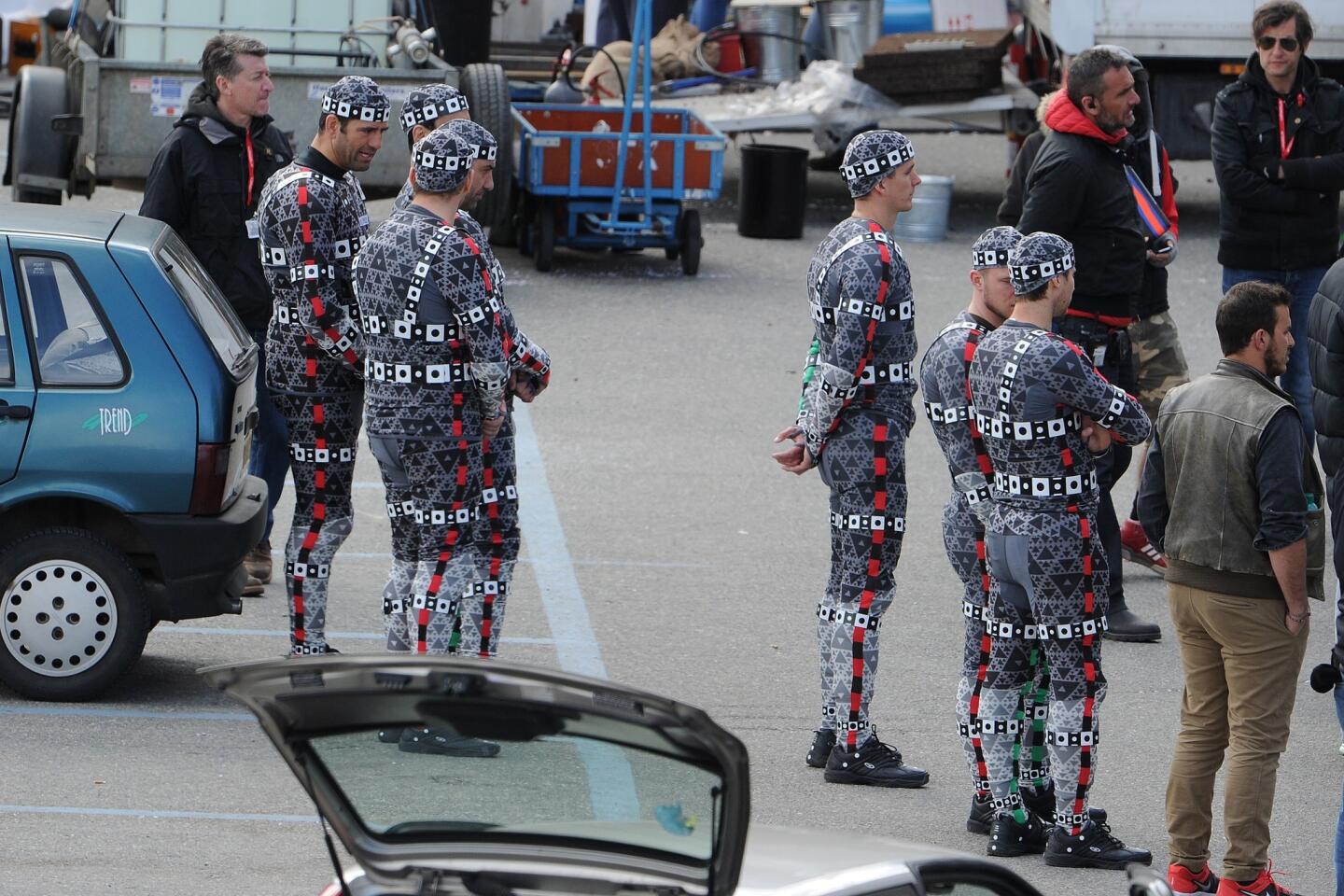

More than that, at least one of the executioners, the documentary’s protagonist Anwar Congo (the man in black in the opening sequence) had a lifelong passion for Hollywood product. So Oppenheimer had the exceptional idea to ask Congo, who claims to have killed more than a thousand people in ways inspired by the movies, his pal Herman Koto (the man in the turquoise dress), and other executioners to re-create on camera, literally, metaphorically, or somewhere in between, the murders they committed.

The scenes Congo (who lives in the North Sumatra city of Medan) and his colleagues come up with are the disquieting heart of the film. In addition to wacky allegories like the one with the giant goldfish, there are film noir scenarios, the re-creation of a fiery attack on a village and a memorable sequence where Congo gets heavily made up to play one of his own victims.

None of this would have been possible without the rapport (Oppenheimer calls it “a genuine intimacy and trust”) that was built up between the filmmaker and the subject, who casually explains he had to come up with new killing methods because beating people to death was creating too much blood.

That connection also allowed Oppenheimer exceptional access to Congo’s world as he mixes with the powerful figures who still run Indonesia. People like Yapto Soerjosoemarno, the head of the 3-million-strong paramilitary group Pancasila Youth, who insists, “we have too much democracy, it’s chaos. All this talk about human rights pisses me off.”

As “The Act of Killing” unfolds, we experience the central place cinema has in psyches worldwide. Even more gripping, we watch as appearing in these re-creations gradually has an effect on Congo he does not anticipate, both disturbing his sleep and serving as a kind of therapy. As Herzog has observed, “these men have escaped justice but they’ve not escaped punishment.”

On a more philosophical level, “The Act of Killing” forces us to acknowledge how we all create our own realities. The pride these murderers take in very particular circumstances, we come to understand, could be duplicated from inside any culture that celebrates any violent act. As Oppenheimer says at the close of a director’s statement, “This is not, finally, a story only about Indonesia. It is a story about us all.”

----------------------------

‘The Act of Killing’

Rating: Unrated

Running time: 2 hours, 2 minutes

Playing: At Nuart, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.