Perspective: An Oscar-nominated director caught up in Trump’s travel ban and lessons learned on a strange trip to Iran

The border guard took my passport and grunted. Two more guards arrived, eyed me, inspected my papers and led me to a room. The door closed. Never a good sign.

It was around 3 a.m. in Tehran’s international airport and my presence had disrupted the calm of a winter’s night. Whispers, asides, a commander was summoned.

Days before I landed in December 2002, the Iranian government had ordered that American journalists be fingerprinted and questioned on entering the country. The decree was in retaliation for “American officials’ insulting behavior toward Iranian nationals.” I sat beneath a portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini. A man walked into the room with a fingerprint pad, ink and paper. He took my hand but seemed confused; the guards pressed in closer, watching.

The man rolled one of my fingers over the pad. Too much ink. The print smudged. He grabbed a second finger. Another unreadable blur. The commander grew agitated. Bursts of Farsi crackled around me; the guards appeared to be giving advice to the man with the ink. The man yelled back. No one was sure of the procedure. What had begun as menacing slipped into farce. The commander sighed and, wanting to regain control of the situation, ordered tea.

The man with ink handed me a tissue. I wiped my stained fingers. The guards laughed. The tea came. Silence fell. We were an American and four or five Iranians with no common language. We nodded and gestured, men caught up in the politics of their governments, stirring sugar and sipping tea in the strange circumstances of the night.

I was reminded of that moment on Sunday when Iranian director Asghar Farhadi announced that he would not be traveling back to Los Angeles next month to attend the Academy Awards. His movie “The Salesman” is nominated for an Oscar for foreign language film. Farhadi’s decision came after President Trump’s executive order to suspend the U.S. refugee program and temporarily prohibit entry to citizens of seven predominantly Muslim nations.

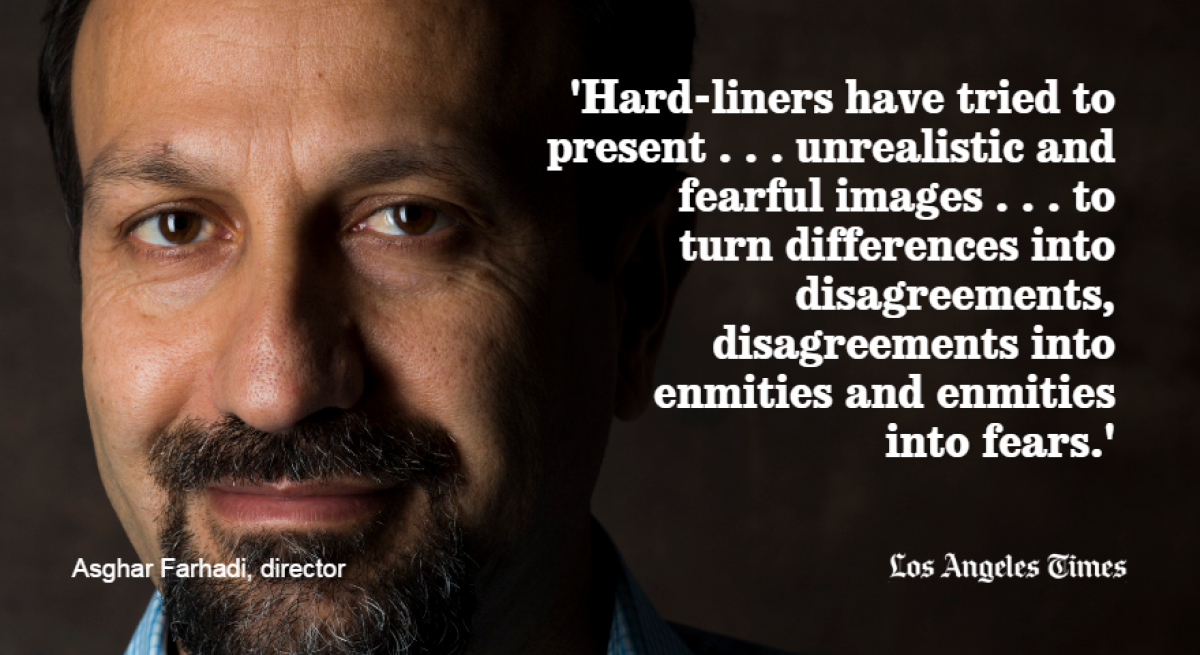

Farhadi could have applied for an artistic waiver, but like Taraneh Alidoosti, the star of “The Salesman,” he decided to take a moral stand. In a statement directed at Trump and Iran’s religious conservatives, he said:

“For years on both sides of the ocean, groups of hard-liners have tried to present to their people unrealistic and fearful images of various nations and cultures in order to turn their differences into disagreements, their disagreements into enmities and their enmities into fears. Instilling fear in the people is an important tool used to justify extremist and fanatic behavior by narrow-minded individuals.”

Farhadi’s films are meditations on what crisis does to the soul, how it forces us to confront not the image of who we want to be, but of who we are. His characters stand unadorned, flawed and imperfect, struggling for but not always finding redemption. Much like ourselves. Not having him at the Academy Awards will diminish the ceremony; filmmakers and actors may praise him from the stage, but it won’t carry the resonance of a conscientious cultural and international voice at a time that the Trump administration is peering inexorably inward.

The U.S. and Iran have been enemies for decades. But there are people beneath the mistrust, wars, terrorism and geopolitical designs that shape their policies. On my 2002 trip to Iran, I drove through the snow to the mountains outside Tehran. Girls in black chadors sledded, boys skied.

I stopped at the home of Bahman Farmanara, a director harassed by Iranian censors over his film about a depraved gynecologist who runs over an angel with his car. We talked about artistic integrity and how much he respected and was shaped by Hollywood films, including “Rear Window” and “All About Eve.”

He even liked the Renée Zellweger movie “Nurse Betty,” saying, “It was a silly thing. A way to escape.... Some films are like Prozac, some like Valium.” But he said it was the art that mattered, the power of film to transcend borders and speak truth.

I was invited to a New Year’s Eve party a few nights later. The taxi dropped me at a high-rise in one of Tehran’s wealthier neighborhoods. I stepped in the elevator. Women shrouded in black abayas, only their faces showing, got in with men in dark suits. Nobody said a word on the way up, and I wondered how much fun the evening was going to be. Alcohol is forbidden in Iran and police enforce religious codes. The elevator doors opened to a penthouse. Music blared. The women peeled off their black robes and danced in short, backless dresses. Their husbands loosened their ties. A man handed me a whiskey.

“Welcome to the real Iran,” he said. “You know, Americans and Iranians are very alike. It is only our governments that make problems.” He paused and held up his glass. “What kind of movies do you like?”

Farhadi, whose 2011 film “A Separation” won Iran its first foreign language Oscar, had similar sentiments when I met him a few weeks ago. “Do you know the answer to ending these wars and violence?” he asked. “The only way is for the people of the world to come to know each other, not through politics but through culture. If people the world over get to see and know each other and understand how similar they are, they would be unwilling to kill one another.”

Instilling fear in the people is an important tool used to justify extremist and fanatic behavior by narrow-minded individuals.

— Asghar Farhadi, director

Immigration bans and a rising global populism threaten cultural exchange. A suspicion of the other is pervading. I felt that, in what turned out to be a harmless hour or so, in that small room in the Tehran airport years ago. When we finished our tea, the commander and the guards stood and the man with the ink tried again. He rolled my finger over his pad and pressed it on paper. A clear print appeared. The fine, curvy lines of identity.

The man smiled and did my other fingers. My hands were a mess when it was done. The guards and the commander were relieved. I was given a box of tissues and sent on my way. The terminal was empty; my bag sat alone near the carousel. I found a taxi and was driven into a city where I had never been, a place that flickered with the art of propaganda iconography, the portraits of martyrs.

I left Tehran in early January 2003, crossing the mountains into northern Iraq. I arrived at the last Iranian outpost. Guards were cleaning their guns and listening to a radio. A few prayer mats were scattered in the dust. The guards looked at me as if I were lost. I handed them my passport and after some consultation they decided I had the right paperwork and wasn’t a spy. They stamped my documents and pointed me down a dirt road to the border. A light rain began to fall.

“War is coming,” one of them yelled.

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

Jeffrey Fleishman’s 2003 stories from Iran:

Iran Living on Edge Between Reformists and Conservatives

Iran Feels Hemmed In by Tough U.S. Rhetoric

ALSO

INTERVIEW: Asghar Farhadi’s new film goes deep into shame and vengeance in Iran

REVIEW: Asghar Farhadi’s ‘The Salesman’ plays out an emotionally complex domestic tragedy

Writers Guild of America calls travel ban ‘un-American’; stands behind Asghar Farhadi

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.