Must Reads: Oscars 2019: ‘Green Book’ is the worst best picture winner since ‘Crash’

“Green Book” is the worst best picture Oscar winner since “Crash,” and I don’t make the comparison lightly.

Like that 2005 movie, Peter Farrelly’s interracial buddy dramedy is insultingly glib and hucksterish, a self-satisfied crock masquerading as an olive branch. It reduces the long, barbaric and ongoing history of American racism to a problem, a formula, a dramatic equation that can be balanced and solved. “Green Book” is an embarrassment; the film industry’s unquestioning embrace of it is another.

The differences between the two movies are as telling as the similarities. “Crash,” a modern-day screamfest that racked up cross-cultural tensions by the minute, meant to leave you angry and wrung-out. Its Oscar triumph was a genuine shocker; it clearly had its fans, but for many its inferiority was self-evident.

Oscars 2019: See the full list of winners and nominees »

“Green Book,” a slick crowd-pleaser set in the Deep South in 1962, strains to put you in a good mood. Its victory is appalling but far from shocking: From the moment it won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival last September, the first of several key precursors it would pick up en route to Sunday’s Oscars ceremony, the movie was clearly a much more palatable brand of godawful.

In telling the story of the brilliant, erudite jazz pianist Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali), who is chauffeured on his Southern concert tour by a rough-edged Italian-American bouncer named Tony “Lip” Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen), “Green Book” serves up bald-faced clichés and stereotypes with a drollery that almost qualifies as disarming.

Mortensen and Ali, who won the Oscar for best supporting actor, are superb performers with smooth timing and undeniable chemistry. The movie wades into the muck and mire of white supremacy, cracks a few wince-worthy jokes, gasps in horror at a black man’s abuse and humiliation (all while maintaining a safe, tasteful distance from it), then digs up a nugget of uplift to send you home with, a little token of virtue to go with that smile on your face.

There is something about the anger and defensiveness provoked by this particular picture that makes reasonable disagreement unusually difficult.

I can tell I’ve already annoyed some of you, though if you take more offense at what I’ve written than you do at “Green Book,” there may not be much more to say. Differences in taste are nothing new, but there is something about the anger and defensiveness provoked by this particular picture that makes reasonable disagreement unusually difficult. Maybe “Green Book” really is the movie of the year after all — not the best movie, but the one that best captures the polarization that arises whenever the conversation shifts toward matters of race, privilege and the all-important question of who gets to tell whose story.

I’ll concede this much to “Green Book’s” admirers: They understandably love this movie’s sturdy craft, its feel-good storytelling and its charmingly synched lead performances. They appreciate its ostensibly hard-hitting portrait of the segregated South (as noted by U.S. Rep. John R. Lewis, who presented a montage to the film on Oscar night) and find its plea for mutual understanding both laudable and heartwarming. I know I speak for some of the movie’s detractors when I say I find that plea both dishonest and dispiritingly retrograde, a shopworn ideal of racial reconciliation propped up by a story that unfolds almost entirely from a white protagonist’s incurious perspective.

“Green Book” has been most often compared not to “Crash” but to an older, more genteel best picture winner, 1989’s “Driving Miss Daisy,” another movie that attempted to bridge the racial divide through the story of a driver and his employer in the American South. “Driving Miss Daisy” was adapted from Alfred Uhry’s play; “Green Book” was co-written by Nick Vallelonga (with Brian Currie and Farrelly), drawn from the stories he heard from his father, Tony. The truth of those stories has been called into question by many, including Shirley’s family, which wasn’t consulted during production and which dismissed the movie as “a symphony of lies.”

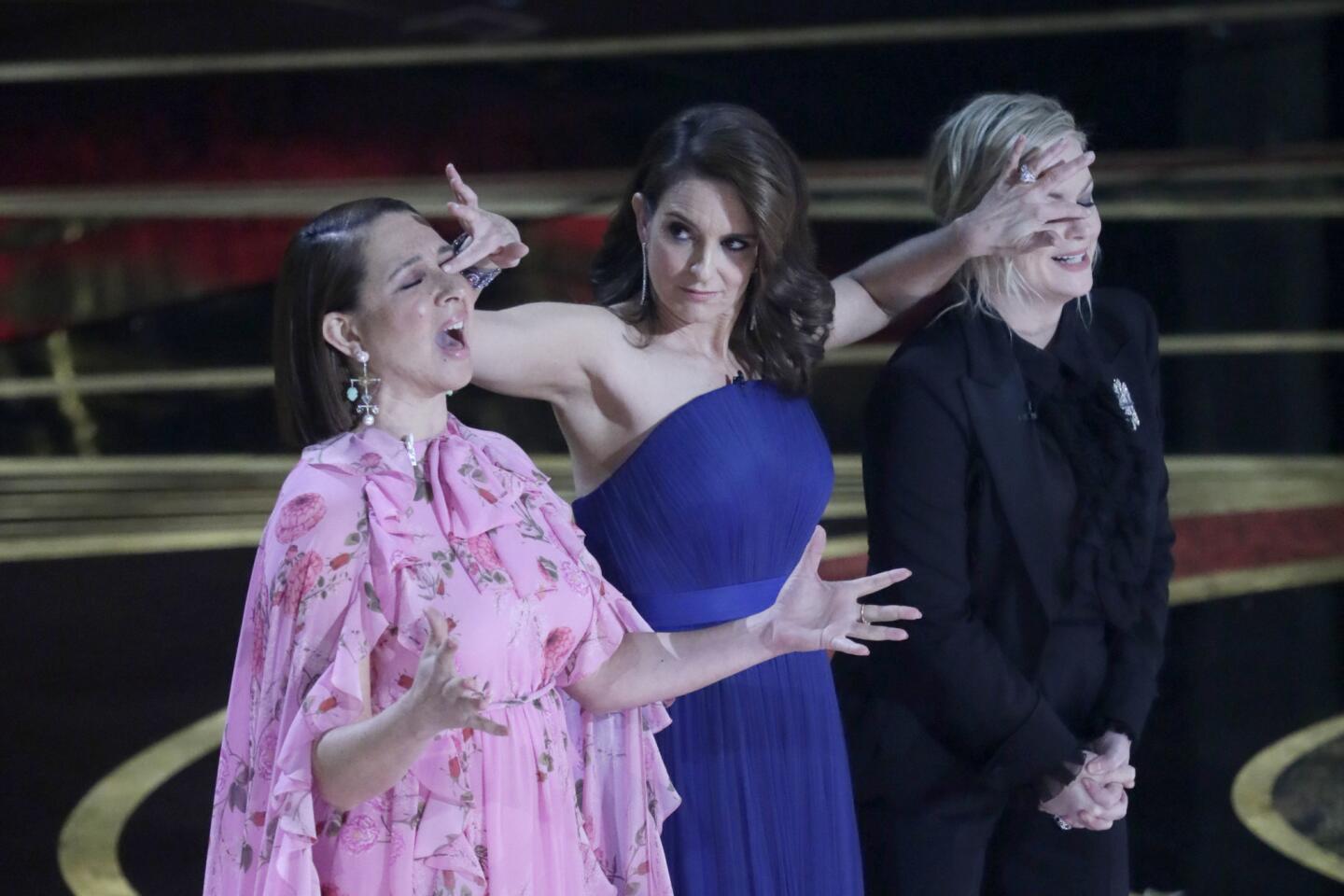

From Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper singing to a ‘Wayne’s World’ reunion, these are the highlights from the 2019 Academy Awards.

Historical accuracy is, of course, just one criterion by which to judge a narrative drawn from real events, and a movie could theoretically play fast and loose with the facts and still arrive at a place of compelling emotional truth. Distortions and omissions can be interesting in what they reveal about a filmmaker’s intentions, and “Green Book,” whether you like it or not, does not have a particularly high regard for your intelligence. In its one-sided presentation and its presumptuous filtering of Shirley’s perspective through Vallelonga’s, the movie reeks of bad faith and cluelessly embodies the white-supremacist attitudes it’s ostensibly decrying.

That cluelessness has been well-documented. Earlier this season, Vanity Fair critic K. Austin Collins pointed out the gall of a white filmmaker blithely psychoanalyzing a black man’s alienation from his own blackness (especially when it takes the form of jokes about Aretha Franklin and fried chicken). Vulture’s Mark Harris aptly described “Green Book” as “a but also movie, a both sides movie” that draws a false equivalency between Vallelonga’s vulgar bigotry and Shirley’s emotional aloofness, forcing both characters — not just the racist white dude — to learn something about themselves and each other.

It’s a tactic, Harris noted, whose echoes can even be found in a terrific older movie (and best picture winner) like “In the Heat of the Night,” and it exists mainly to reassure any audience that might be uncomfortable with a black man gaining the moral high ground.

You would hope that in 2019 — even in a 1962-set movie — such strategic pandering would be a thing of the past. But in “Green Book,” we should be especially nauseated by how crudely the deck is stacked against Don Shirley from the get-go. A more honest, complex and tough-minded movie might have run the risk of actually becoming Shirley’s story, of letting the much more interesting of these two characters slip into the metaphorical driver’s seat. (The fact that Ali was pushed as a supporting actor to Mortensen’s lead campaign is telling in all the wrong ways.) But there isn’t a single scene that feels authentically like the character’s own, that speaks to Shirley’s experience and no one else’s.

His intelligence and elegant diction is continually Otherized. (Vallelonga’s intellectual inferiority is mocked as well, but the picture’s sympathies couldn’t be more clearly on his side.) The movie makes little attempt to parse or appreciate his musical gifts critically; Shirley’s artistic brilliance, much like his alcoholism or his homosexuality, is deemed interesting only insofar as it changes Vallelonga’s opinion of him.

It’s telling that what should be Shirley’s most emotionally lacerating scene — he’s busted for having sex with another man in a YMCA shower — instead becomes the movie’s most reprehensible. If you want to know what a profound lack of empathy looks like, take another look at that shot of Vallelonga sweet-talking the cops while, in the background, a naked black man sits handcuffed in the shower, terrified and humiliated.

It’s strangely troubling that Ali — who won his first supporting actor Oscar for 2016’s “Moonlight,” an achingly beautiful portrait of gay black masculinity — has now won another award for playing a gay black man in a movie that has so little respect for his identity. There’s an even ghastlier irony in the fact that the academy that broke new ground by giving its highest honor to “Moonlight” two years ago has now seen fit to bestow the same prize on a movie that is “Moonlight’s” complete aesthetic, emotional and moral antithesis.

It’s one thing to like “Green Book,” but it takes a highly specific set of blinders to declare it the year’s finest cinematic achievement in the wake of this year’s many better alternatives, Spike Lee’s tough, provocative “BlacKkKlansman” not least among them. The fact that the academy embraced “Driving Miss Daisy” in the same year it overlooked Lee’s great, incendiary “Do the Right Thing” gives Sunday’s Oscars broadcast the sickening sense of history repeating itself: “BlacKkKlansman” at least received nominations for picture and director, but in the end it too lost out to a (much worse) two-hander peddling can’t-we-all-just-get-along bromides.

And that’s to say nothing of best picture nominees like “Black Panther,” the rare Hollywood blockbuster that examines the nuances of African and African American identity without undue concern for a white audience’s entry points, or the innumerable terrific, tough-minded movies about racial justice, like “If Beale Street Could Talk,” “Sorry to Bother You,” “Support the Girls” and “Widows,” which voters couldn’t be bothered to nominate for best picture, assuming they saw them in the first place. (The year’s best interracial buddy movie, by the way, wasn’t “Green Book”; it was every exchange between Viola Davis and Elizabeth Debicki in “Widows.”)

Over the next few days and weeks there will undoubtedly be a lot of theorizing about what happened. Some will zero in on the failure of an academy whose taste clearly isn’t quite as evolved as its rapidly diversifying and internationalizing membership would suggest. Still others will be tempted to identify a stubborn strain of Trumpian anti-intellectualism among “Green Book” lovers who dug in their heels in defense of a much-maligned favorite.

They may have a point. I remain optimistic that, as with “Crash’s” ill-remembered victory, the coronation of “Green Book” will turn out to be not a re-entrenchment but a calamitous fluke — the academy’s last concession (for now) to that portion of the white moviegoing audience that still believes stories of justice and progress will always have to be negotiated on their terms. As Shirley tells Vallelonga early on in “Green Book”: “You can do better.” His rebuke might just as well extend to the movie he’s in and to a voting body foolish enough to honor it.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.