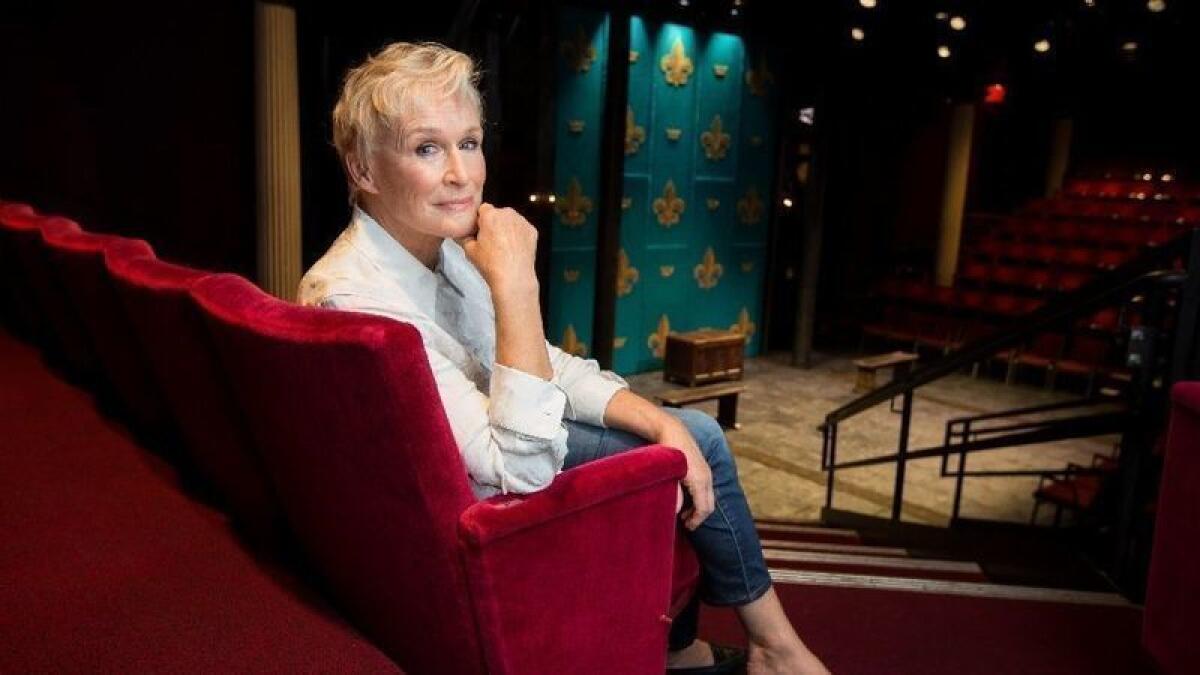

Commentary: Glenn Close doesn’t need an Oscar, but this year she deserves one

Glenn Close doesn’t need to win an Oscar.

This really needs to be said, out loud and with conviction, possibly several times, as a protection spell against the alarming awards season narrative that followed her outstanding performance in “The Wife,” for which she did indeed receive an Oscar nomination.

Ever since the film’s fall debut, and especially after her Golden Globe win (over, gasp, Lady Gaga), a narrative has formed in which Close could win this year even though her film slid beneath the awards radar because, well, she has never won before. And for Close to have been nominated for an Oscar seven times and not win once would be, according to that always just and sympathetic entity conventional wisdom, just plain wrong.

Well, it would be wrong for the academy if she doesn’t win this year, but not for Glenn Close.

The woman has won three Tonys, three Emmys and three Golden Globes. In 1984, she was nominated for a Tony, an Emmy and an Oscar for three separate projects (“The Real Thing,” “Something About Amelia” and “The Natural.”)

She doesn’t need an Oscar to prove that she is a master of her profession, virtually unlimited in her range, remarkably courageous in her choices. She has played a cross-dressing Irishman, Cruella de Vil, the only woman to give Michael Douglas what he deserved and “Sarah, Plain and Tall” with equal power and panache. She made crying in the shower, and handing your husband over for a night’s adultery, believable in “The Big Chill.” She granted women anti-hero status with “Damages.”

FULL COVERAGE: 2019 Oscar nominations »

Indeed, decades before it was acceptable in Hollywood, she moved between film, stage and television in roles that were often startling but rarely showy (though you can’t do Cruella or “Sunset Boulevard” without a little showy).

Should she have won for “The World According to Garp” over Jessica Lange in “Tootsie”? Probably. For “Fatal Attraction” instead of Cher for “Moonstruck” or for “Albert Nobbs” over Meryl Streep in “The Iron Lady”? Maybe.

Should she win this year for “The Wife” over Lady Gaga in “A Star is Born” or Olivia Colman in “The Favorite”?

Yup, but not because she is “owed” or “needs” an Oscar.

She should win because her performance was riveting, subtle and painfully naked in a film that explores the difficulties women face when pursuing a creative career, and not just the obvious ones.

In “The Wife,” adapted by Jane Anderson from Meg Wolitzer’s novel, Close plays Joan Castleman, whom we meet as the quiet power behind Great American Writer Joe Castleman (Jonathan Pryce). Joe is precisely that figure of yarn-spinning, dinner-party charm threaded with arrogant self-deprecation and carefully curated self-doubt that we have come to expect from men of genius, especially in movies.

Joan meanwhile quietly keeps everything moving and, spoiler alert, writes the books.

RELATED: Glenn Close reflects on her 7th Oscar nomination and that ‘spontaneous’ Globes speech »

The movie, with the exception of Close’s performance, was received kindly if a little coolly. It is not the way Hollywood likes to tell these sorts of stories. It is not “Norma Rae” or “Out of Africa.” Joan is not an activist or a pioneer; she is a writer. Early on, she accepts that she will not be taken seriously, as Joe is, in large part because she is a woman but also because she does not have the talent for self-promotion that he has.

One can argue that the first bit (she’s a woman) ensures the second bit, and another story, and most certainly another movie, would pit Joan against those social forces (see please “Colette”). Another story would have made her a more typical heroine who not only reveals herself as the writer of the award-winning novels but also stands up on tables or wears amazing hats and inevitably changes the world.

Instead we have the story of a woman who has made many compromises to ensure that she never had to make the biggest one: She has been able to write exactly as she chose and see those books published, honored and praised. She does not appear to need the adulation her husband craves, so she has managed to convince herself it all worked out OK.

Only now she is older, and with Joe is being given the Nobel, she realizes the injustice of it all, feels the excruciating pain of realizing not just that she has denied herself credit but that even her husband values the myth of the Great American Writer over the reality.

She has sold short not only herself but her marriage and, perhaps most important, her art.

It is telling that the best actress category is filled with characters trapped by social expectations: Melissa McCarthy’s misanthropic and marketing-averse Lee Israel in “Can You Ever Forgive Me?”; Olivia Colman’s tragic-comic Queen Anne in “The Favorite”; Yalitza Aparicio’s sex- and class-confined domestic worker in “Roma.” Even the triumph of Lady Gaga’s Ally comes at an emotional cost.

But Close tells Joan’s epic internal journey, and the meaningful social one, with few of the typical narrative conventions and relatively minimal dialogue. Throughout the film, her face and body perform a symphony of emotion with the smallest movement. Answering a phone, taking her husband’s coat, staring out a car window, reacting to applause — in fleet seconds, Close reveals, with heart-wrenching clarity, more of the reverberating damage done by a society in which only a certain type of person is encouraged to achieve than most performers manage in an entire movie.

To undercut such a feat by suggesting that her nomination or win is based on anything but her performance in “The Wife” is just more painful proof of the film’s central truth: that we only recognize excellence when it comes wrapped in a certain kind of package.

Glenn Close doesn’t need an Oscar to prove anything; she’s already proved it. But an institution that purports to reward excellence most certainly needs to give her one. For “The Wife.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.