After a string of Oscar season stumbles, the motion picture academy and its leadership are at a crossroads

On Sunday night, millions of viewers around the world will finally find out who the big winners are in this year’s Academy Awards. But, after an unusually tumultuous and controversy-filled Oscar season, some would argue that one of the big losers has already been revealed before a single envelope has been opened.

Unfortunately, it’s the motion picture academy itself.

The venerable institution, which prides itself on representing Hollywood’s best and brightest, is heading into its most important and most glamorous night looking somewhat rudderless and half-dressed. For the first time in 30 years, the Oscars will have no formal host after Kevin Hart dropped out in December amid a firestorm over past homophobic tweets and jokes, leaving empty a gig that was once coveted but is now widely considered thankless.

As embarrassing as the Hart debacle was for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, though, it was just one of a number of black eyes the organization sustained in the run-up to this year’s Oscars, nearly all of them self-inflicted.

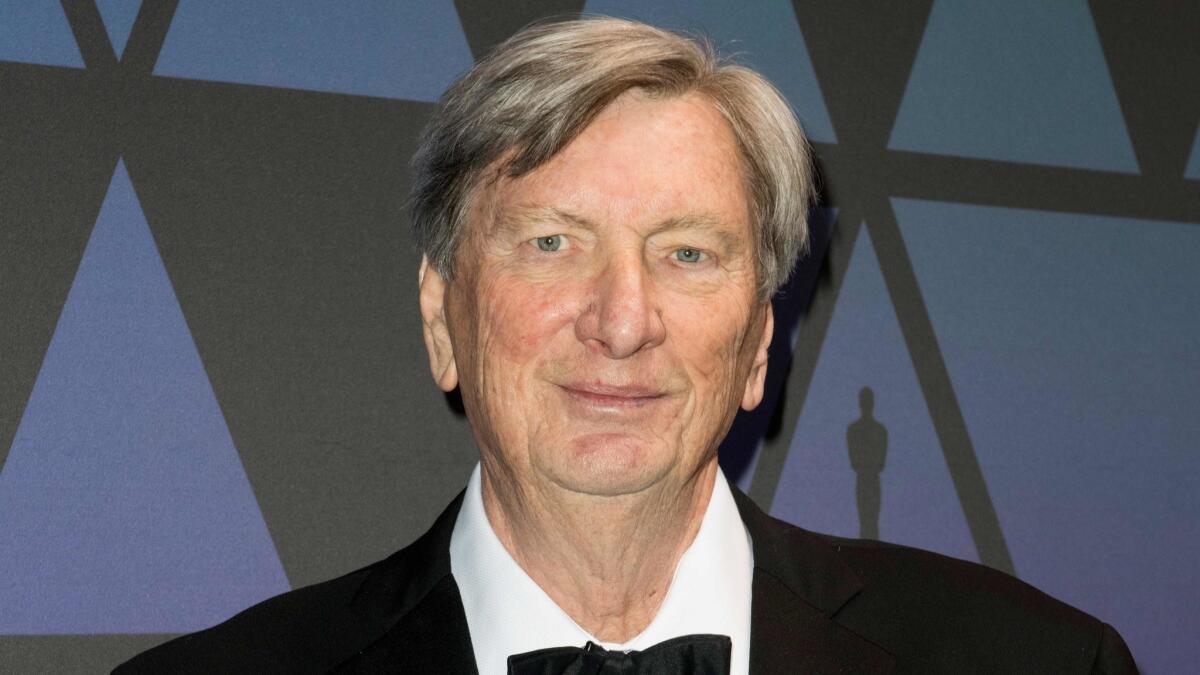

As the academy has stumbled through a string of public-relations crises — from a scrapped proposal to create a “best popular film” award that was widely criticized as pandering to a much-maligned and ultimately abandoned plan to move the presentation of several awards to commercial breaks — questions have been raised about how the organization is being run under President John Bailey and Chief Executive Dawn Hudson, as well as its 54-member board of governors.

“Not quite sure why the Academy Awards seems to hate the Academy Awards this year,” actor Josh Gad pointedly wrote on Twitter last week, joining hundreds of industry professionals protesting what they saw as a misguided plan to snub some of filmmaking’s most important crafts simply to shave a few minutes off the often-bloated telecast.

To many, the recent missteps and reversals reveal an institution at a crossroads, pulled in one direction by the need to adapt to a rapidly changing entertainment landscape and in the opposite direction by nearly a century of proudly held traditions.

And as the academy looks ahead to further challenges, including the opening of a long-delayed, highly anticipated $388-million museum scheduled for late this year, the group’s leadership — which will undergo a transition later this year with elections to replace Bailey as well as some board members — is likely to continue to draw scrutiny.

With the ratings for the Oscars steadily sliding in recent years, maintaining the show’s relevance is a top priority for the academy, which derives the bulk of its revenue from the show. (According to the group’s most recent annual report, despite last year’s lowest-ever ratings, returns from the Oscars were nearly $131.8 million, up more than 7% from 2017.)

But as this year’s turbulent awards season has proven — with controversies that at times pitted the academy’s leadership against some of its most esteemed members — getting everyone on the same page about how to do that is no easy feat.

2019 Oscars: See the full list of nominees »

“People in the academy have different views,” said producer and former studio executive Bill Mechanic, who served on the academy’s board before resigning in protest last year over what he saw as poor management of the organization. “You have the purists who don’t want any change. But you’ve got to come to some kind of solutions. … Or you just keep losing audience.”

Indeed, both within the academy’s leadership and its membership, which has grown by 30% in three years — in large part to diversify the disproportionately white, male ranks — there is a degree of division over what the Academy Awards, now in their 91st year, mean in today’s world.

Some regard the Oscars as a glitzy, star-studded entertainment show that needs to change with the times to attract an increasingly distracted and fragmented audience. Others see it as a hallowed celebration of the finest in filmmaking whose traditions should be upheld at all costs, even if it means a potentially wearying running time and lower ratings.

“I think the show has made many mistakes,” producer and director Judd Apatow told The Times last week, pointing, among other things, to an apparent early plan, also reversed, to cut performances of some of the best-song nominees from the telecast. “I understand the demands of time, but I think people would rather have a great show than a rushed show with less awards and less entertainment.”

Even as the academy has sought ways to remake the Oscars, the institution has been remaking itself from the inside out over the past several years. In response to the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, the organization has taken bold steps to diversify and expand its historically white male-dominated membership, steps for which it has been widely applauded. Last summer, the academy invited a record-setting 928 new members, 49% of them female and 38% of them people of color.

But at the same time, fissures have sometimes opened up in the group’s leadership structure — which many consider unwieldy, with ill-defined divisions of responsibilities — over key issues such as the museum, which has gone over budget and over schedule, and how best to respond to the #MeToo movement.

Heightening the uncertainty, changes are set to come to that leadership soon. Annual elections for the board of governors will be held this summer. Bailey’s run as president will conclude in August due to term limits, while Hudson’s contract runs through 2020.

Bailey and Hudson declined to comment for this story. But, speaking to the Times in September, Bailey acknowledged that, when it comes to how to revitalize the Oscars, there are varying opinions among the academy’s board, which includes such luminaries as Steven Spielberg, Laura Dern, Whoopi Goldberg, and Paramount Pictures chairman and CEO Jim Gianopulos.

“You’ve got 54 alpha-type people that are highly creative, highly motivated — I mean, it would be absurd to say it was unanimous,” Bailey said of the “best popular film” proposal. “We are just trying to address what we see as an existential problem that has been there for a number of years and is not going to go away in terms of where films seem to be headed.”

Still, Bailey brushed aside the criticism that the academy lacked a coherent vision for how to deal with that existential problem, making decisions in a knee-jerk fashion.

“Look, for an organization that some people like to say is irrelevant and is out of touch with the times, there always seems to be a tremendous amount of interest in what is going on inside the academy,” he said. “My own feeling is, no matter what the academy does or says or determines as a course of action, there are going to be naysayers. It’s just the nature of it.”

Hudson, who has served as CEO since 2011, has at times been a polarizing leader. While many within the organization credit her with helping spearhead the academy’s push toward diversity and the building of an ambitious museum, others feel that under her leadership the academy has moved too quickly in too many new directions, drifting from some of its core missions and alienating some members.

Speaking to The Times in 2017, Hudson acknowledged that she has at times been a lightning rod. “There’s an idea of change and then there’s actually going through change — and sometimes it’s harder to go through it,” she said.

Others have directed criticism at Bailey, who is a veteran cinematographer, for taking the lead in promoting the much-criticized “best popular film” idea and for not shielding the below-the-line crafts from the proposed changes to the awards presentation. In contrast with his predecessor, Cheryl Boone Isaacs, who came from a marketing and public relations background, some regard Bailey as less adept at dealing with the media — a key role of the academy president even in more tranquil times.

American Society of Cinematographers president Kees van Oostrum — who became the de facto leader of a large grass-roots movement that fiercely opposed the plan to shift the presentation of four awards to commercial breaks — defended Bailey, however, saying he shouldn’t be held responsible for the mess that ensued.

“People have to understand that the motion picture academy is run by an executive board and the presidency is an honorary title,” Van Oostrum said. “A lot of people were pointing the finger at Bailey, and I don’t think that was completely justified. I’ve known him as an extremely ethical person. I think there was a lot of pressure within the academy from the executive branch to go this route.”

Looking ahead, Van Oostrum argues that, whoever is at the academy’s helm, the recent controversies starkly demonstrate the need for closer communication between the group’s leaders and its rank-and-file members.

“Let’s learn from this that maybe a governmental system that has been in place for many, many years needs to be adjusted to today’s norms,” he said. “Today’s norms are that we communicate and we don’t just have to function with some elected officials. We encourage them in the future, let’s be in touch. Let’s all together work for a better Academy Awards next year.”

In the meantime, while this awards season has certainly involved a number of major headaches for the academy and for the producers of this year’s Oscars, Donna Gigliotti and Glenn Weiss, not everyone thinks it will necessarily result in any significant damage.

Indeed, Mechanic speculated, the fumbles and whipped-up outrages could drive interest in the show even higher, even if some viewers are just curious to see if it proves a train wreck.

“Controversy is not a bad thing,” Mechanic said. “It sells newspapers. It sells movies and television shows. So if I’m Donna, it might not make my life easier but it might make my show better.”

Times staff writer Glenn Whipp contributed to this report.

Twitter: @joshrottenberg

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.