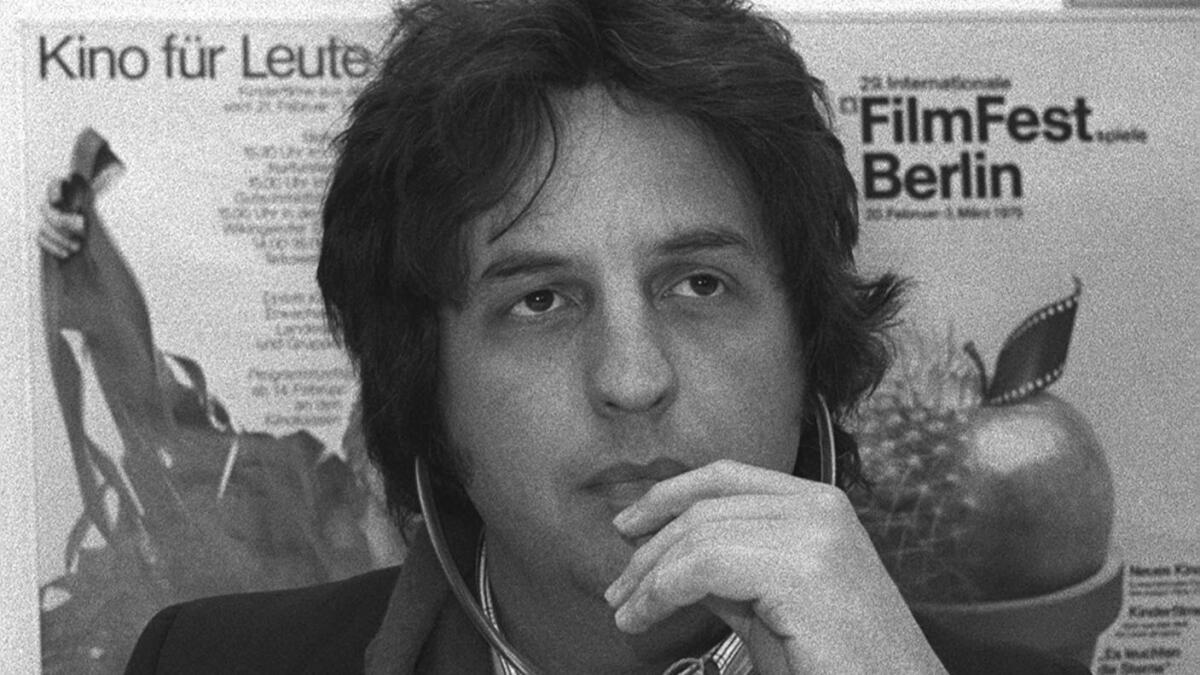

Appreciation: Michael Cimino, a ‘Hunter’ in pursuit of an uncompromising vision

It is impossible to mourn the death Saturday of Michael Cimino without confronting the loss of what he and his New Hollywood ilk represented: an audacious, ecstatic, sensuous, deranged and ultimately staggering vision of what the movies could be, and a willingness to pursue that vision utterly without compromise.

It was a costly vision, to be sure — by which I mean more than just the well-documented financial fiasco of “Heaven’s Gate,” the ravaged and ravishing 1980 western that broke United Artists, hastened the death of a ’70s auteur renaissance and dealt Cimino’s career a blow from which it never recovered. Coming on the heels of his critical and commercial success with the Oscar-winning “The Deer Hunter” (1978), “Heaven’s Gate” remains, for many, the definitive Hollywood cautionary tale of filmmaker hubris run amok (as compellingly detailed in the tell-all book “Final Cut” by Steven Bach, a former UA executive who was involved with the production).

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Three decades after being critically eviscerated, yanked from theaters and largely kept out of public view, Cimino’s epic of community and class warfare may yet experience the happy ending that eludes its characters as they lurch across the frontier terrain of 1890s Johnson County, Wyo. No shortage of critics and cinephiles have reclaimed the picture as a misunderstood masterpiece, many of them arguing on the strength of a beautiful Criterion Collection restoration, supervised by Cimino himself, that began playing festivals and repertory houses in 2013.

To experience “Heaven’s Gate” anew — and it is indeed a thing to be experienced, with an open eye and an even more open ear (some of the dialogue remains famously muddled) — is to gape at its magnificence and also sense the price that the director paid for his perfectionism. Cimino was clearly bleeding more than just his budget dry. You can still feel his heart pouring out on-screen in every dust-swept frame of Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography, in stunning outdoor shots where Cimino seems to have choreographed the very movement of the sun and the clouds. And you can feel it, too, in a drama poised on a knife’s edge between grandeur and arrogance, and in performances (from Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, John Hurt, Jeff Bridges and Isabelle Huppert) that, however striking, struggle to cohere under the force of the director’s unyielding gaze.

What the director was looking for, amid the endless reshoots and nearly 250 miles of accumulated footage, was not just a narrative but a panorama — a full-bodied portrait of working-class American life, filled with moments of languorous intimacy that would soon be subsumed in a whirlwind of violence. It’s no overstatement to suggest that he was trying to give cinematic form to the lost, brutalized soul of America itself, and to create an epic human tragedy that would not just equal but eclipse his earlier landmark.

If the legacy of “Heaven’s Gate” continues to shift and expand, then “The Deer Hunter” still retains its raw and unruly dramatic power; it may have long since given up its claim to being the definitive movie about the Vietnam experience, but it remains a shattering and indelible one nonetheless. What Cimino’s portrait of a Pennsylvania family of Russian-American steelworkers may have lacked in credibility and nuance, it made up in the blazingly committed performances of Robert De Niro, Walken, Meryl Streep and John Cazale, and in its bone-deep empathy with characters whose pain and disillusionment reverberated with the audience’s own.

By dint of its confrontational subject matter, “The Deer Hunter” had direct access to a nation’s shell-shocked psyche in a way that the more historically remote “Heaven’s Gate” would not. Yet the films are best appreciated now less as polar opposites (triumph vs. failure) than as companion pieces — twin monuments to his towering ambition that scorn the rules of traditional narrative construction and conform to no expectations but Cimino’s own. The long and justly celebrated wedding set piece that occupies the first act of “The Deer Hunter” finds an echo in the leisurely, lovingly choreographed scenes of dancing and roller skating in “Heaven’s Gate,” and in the ungovernable swirl of the characters’ romantic passions, gathering just before the storm.

Few American directors working inside or outside the contemporary mainstream are willing to subject their audiences to this sort of full-scale immersion. Cimino, hailing from an earlier era of artistic freedom, was willing to indulge his longueurs because for him, they weren’t beside the point in a film about the beauty and fragility of community; they were precisely the point. It was essential to his purpose that we felt — as much on a sensory level as a narrative one — the weight and texture of lives that were about to change forever.

Writing about “Heaven’s Gate” in 2012, the New Yorker critic Richard Brody suggested that, had the film been released in the Internet age, critics would have turned it into “a succès d’estime, not after 32 years but from the start.” It’s hard not to wonder if Cimino might have benefited still further from the support of such an adventurous critical fan base — one that, with its willingness to defend challenging art and defy consensus, might have helped this great and famously difficult American iconoclast shake off his inertia and reclaim, or even reinvent, his identity as a filmmaker.

There are fleeting glimpses in Cimino’s lesser-known pictures of what that identity might have been. He began his career as a co-screenwriter on films as different as Douglas Trumbull’s 1972 oddball sci-fi classic “Silent Running” and the 1973 “Dirty Harry” sequel, “Magnum Force” (which he scripted with John Milius, another New Hollywood contemporary). It was Clint Eastwood who gave him his big break by letting Cimino direct his own script for “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot” (1974), a hugely entertaining buddy action-comedy that remains as notable for the effortless rapport between Eastwood and Bridges (who received an Oscar nomination for the role) as for its underlying grit and intensity, plus Cimino’s already clear fascination with the endlessly expressive qualities of the American landscape.

Five years after “Heaven’s Gate,” Cimino reemerged with some of his flair and seriousness regained in “Year of the Dragon” (1985), a propulsive crime thriller that cast a terrific Mickey Rourke into the seedy criminal underworld of New York’s Chinatown — a world that, as with the immigrant communities populating his earlier work, Cimino delved into with furious abandon. He didn’t entirely pull it off; the charges of xenophobia that greeted his portrait of the Viet Cong in “The Deer Hunter” were echoed by similar criticisms of “Dragon’s” Chinese-American characters, who, despite Cimino’s honest attempts to explore rather than exploit their marginalized culture, were let down by unpersuasive performances and banal plot turns.

In a lengthy 2015 interview with the Hollywood Reporter, his first after years spent in retreat from the industry and the public eye, the director said, “Your favorite film is always the film you haven’t made yet.” Burned out after a string of flops and misfires including “The Sicilian” (1987), “Desperate Hours” (1990) and the Woody Harrelson-starring “The Sunchaser” (1996), and with countless unfinished dream projects abandoned by the wayside, Michael Cimino didn’t live to see the promise of that statement fulfilled. It’s something to be lamented, perhaps, with more resignation than regret: The industry that might have sustained his career, in all its thrilling and ludicrous enormity, collapsed long before he did.

[email protected] | Twitter: @JustinCChang

ALSO

Jesse Williams and the academy just changed Hollywood’s race conversation. What’s next?

‘Please don’t forget what he taught us’: Elie Wiesel is remembered as a heroic humanitarian

Anime Expo is more than just cosplay — but there’s a lot of cosplay

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.