Appreciation: With ‘Rocky’ and ‘The Karate Kid,’ John G. Avildsen beat the odds

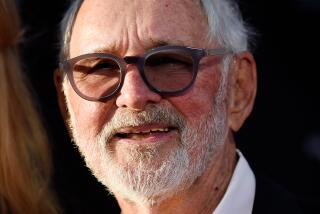

It’s been noted that the director who gave us two of the most cherished underdog sagas in American movies remained, to the end, something of an underdog himself. John G. Avildsen may have secured his place in the Hollywood firmament with “Rocky” (1976) and “The Karate Kid” (1984), both fitting tributes to the importance of working hard, staying tough and keeping your eyes on the prize. But those soaring career highs stood out in a career that also encompassed high-profile duds, ill-advised sequels, Troma sexploitation flicks and a trio of Razzie nominations. It was not, to be sure, your typical Academy Award winner’s résumé.

But so what? Avildsen, who died on Friday at 81, was more uneven journeyman than exacting artist, the kind of director who gamely tried his hand at any number of genres, misfired often and seemed to stumble onto his successes almost by accident. But that lack of pretension — another word for it might be subtlety — made sense for a filmmaker who was, at his best, a master of the sturdy and the sentimental, who excelled at telling scrappy, emotionally generous stories about improbable winners, perpetual losers and everyone in between.

That so many of these characters spring so vividly to mind is a reminder that Avildsen, while not always inspired in his choice of material, had an often sure-handed touch with actors. Sylvester Stallone’s original appearance as Rocky Balboa, for all its endlessly imitable meathead toughness, seems all the more striking today for its delicacy. The performances given by Peter Falk in “Happy New Year” (1987), Molly Ringwald in “For Keeps?” (1988) and Morgan Freeman in “Lean on Me” (1989) rank among their personal bests.

Despite his facility with actors, Avildsen wasn’t afraid to clash with his collaborators in front of the camera or behind it. Off-screen disputes may have been at least partly to blame for the fiasco of “The Formula,” his dead-on-arrival 1980 thriller starring Marlon Brando and George C. Scott. The director’s battles with John Belushi on the set of the 1981 suburban comedy “Neighbors” similarly became the stuff of industry cautionary-tale legend.

At one point Avildsen was slated to direct both “Serpico” (1973) and “Saturday Night Fever” (1977) until his disputes with producers led to his removal from both pictures. And while I imagine few movie lovers are mourning the outcome in either case, it’s still fascinating to imagine what these New Hollywood touchstones might have become in his hands.

An answer of sorts is provided, I think, by Avildsen’s darkest, most unnerving picture, “Joe” (1970), which starred Peter Boyle as a bigoted factory worker with a long-simmering grudge against the hippie counterculture. As a study in bigoted white-male rage exploding in a climactic burst of violence, this low-budget audience sensation may have been Avildsen’s most prescient movie. And, like his fine 1973 drama “Save the Tiger,” which earned Jack Lemmon an Oscar for his performance as a middle-aged garment manufacturer at the end of his rope, it bracingly suggests there was perhaps more to this director than soaring music and insistent uplift.

But in the end, it is precisely that uplift to which we return when we think of him, and rightly so. Both “Rocky” and “The Karate Kid” (and, to a less captivating extent, its two Avildsen-directed sequels) are emphatic, rousing entertainments, awash in training montages, important lessons about love and mentorship, and any number of sports-movie conventions that they effectively put into circulation. Generation after generation, their hold on the mass audience’s affections remains unassailable.

“Rocky” in particular endures for a number of reasons, the unanimous approval of critics not being one of them. That the movie is often described as “irresistible” is hardly unqualified praise, insofar as it carries the lingering suggestion that it should, on some level, be resisted. The film’s Oscar triumph has often been held up, rightly or wrongly, as a scornful reminder of how little regard the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has for the opinions of professional tastemakers.

But for audiences that care more about stories and emotions than, say, the relative merits of best picture rivals “All the President’s Men,” “Network” and “Taxi Driver,” “Rocky” largely works as well as it did 40 years ago. You thrill to the ecstatic surge of the score by Bill Conti (who remained a steadfast collaborator to the end of Avildsen’s career), and are moved by the grit and tenderness of its working-class Philadelphia milieu.

Most of all, perhaps, you are stirred by the unfashionable optimism of its belief that someone young and untested, but large in ambition and spirit, might have the makings of a champ. At his best, John G. Avildsen himself proved worthy of that legacy.

ALSO

Sylvester Stallone says a ‘Rocky’ reshoot made him understand the term ‘movie magic’

Oscar archives: In ‘77: ‘Rocky,’ posthumous honor and Scorsese snub

Director John Avildsen had hard-hitting films before ‘Rocky’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.