Indie Focus: Norway’s Joachim Trier shakes things up with his English-language film ‘Louder Than Bombs’

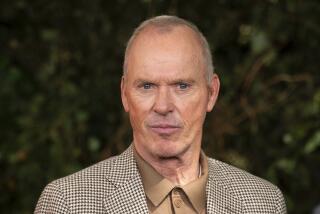

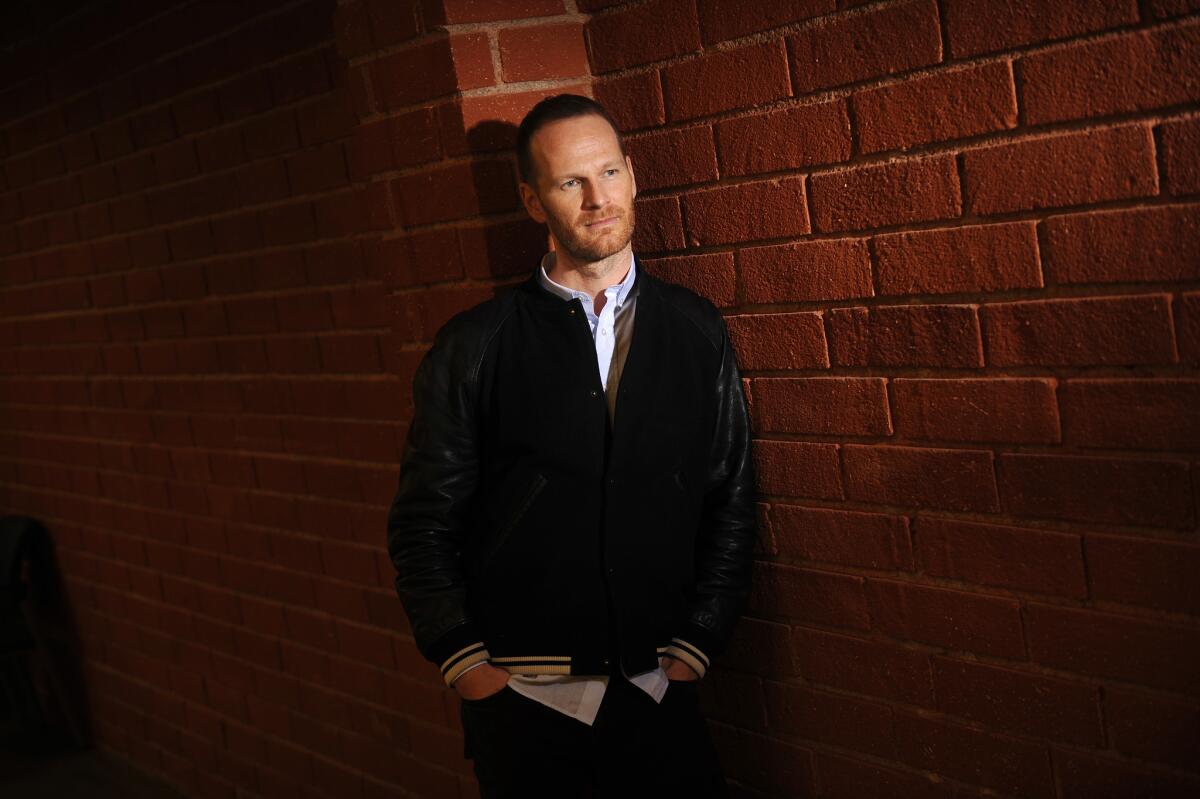

Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier

Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier burst onto the international scene with “Reprise” and “Oslo, August 31st,” two movies that mixed a deep-rooted sense of character drama with a playful self-awareness for structure and performance. Their mix of dark and light made them both feel, above all else, fresh.

Introducing his new film, “Louder Than Bombs,” at its recent Los Angeles premiere, he noted that it was not as unusual as it might seem that he had made an English-language story set in a leafy enclave outside New York City.

“I’m from Norway,” Trier said, “the suburbs of Europe.”

The picture had its world premiere last year in the high-profile, high-intensity main competition of the Cannes Film Festival, arguably world cinema’s brightest spotlight. The movie tells the story of a family torn apart by grief and struggling to come back together in some new configuration.

Three years after the death of Isabelle Reed (Isabelle Huppert), a highly regarded photographer of war and conflict, her husband, Gene (Gabriel Byrne), and sons Jonah (Jesse Eisenberg) and Conrad (Devin Druid) are struggling to move forward. Jonah is not responding well to his own new fatherhood, while there are things teenage Conrad still doesn’t know about his mother’s death. An impending gallery exhibition of Isabelle’s work and a newspaper article by her former collaborator Richard (David Strathairn) bring all their issues to the surface.

Even though he has made a movie in English, in America, with name actors, Trier — who cowrote “Louder” with Eskil Vogt — has not exactly gone Hollywood. But he has embraced it.

“Remember, I come from a country of only 5 million people speaking my language. I must allow myself to try to do something in the lingua franca of cinema, in English, in America,” Trier said.

“It’s not such a strange thing for me to do, but I somehow wanted these images of a family living in an autumn leaves atmosphere, driving a Volvo in upstate New York. Or maybe Illinois in ‘Ordinary People’ country. I feel at home in those places. They remind me very much of Scandinavia.”

Trier is proud he’s a third-generation filmmaker; his grandfather Erik Løchen directed a movie called “Jakten” that played the Cannes competition in 1960. A skateboarding champion in his youth, he attended film school in London and lived there for seven years before returning to Norway.

Trier mentions not just “Ordinary People” and “The Ice Storm” as influences on “Louder” but also “The Breakfast Club” and “Risky Business” for their abilities to fuse teen-centric entertainment with thoughtful, emotional character moments. (“Louder” even knowingly features a Tangerine Dream song from the “Risky Business” soundtrack.)

Both “Reprise” and “Oslo, August 31st” garnered Trier attention that far outweighed the modest box office returns of their limited theatrical releases. Powerhouse producer Scott Rudin came aboard “Reprise” as an executive producer for its American release. Trier’s collaborators have been recruited for American productions, with his cinematographer Jakob Ihre shooting the David Foster Wallace elegy “The End of the Tour” and editor Olivier Bugge Coutté working on Mike Mills’ “Beginners.”

Yet where a filmmaker like Trier fits into the world of contemporary Hollywood is something he is searching for the answer to himself.

“It’s an open question, and I’m not criticizing anyone, but is there a place for someone like me in the American studio system today, question mark,” Trier asked. “My feeling is at the moment, I am interested in an American film tradition that I grew up with that I don’t know where it exists right now.”

Trier noted how “Louder Than Bombs” was one of a number of English-language movies made by international filmmakers in last year’s main competition at Cannes that also included Yorgos Lanthimos’ “The Lobster” and Paolo Sorrentino’s “Youth.” Though the response there was muted and muddled — the Guardian called the film “Euro-American pudding” — the picture has been received more warmly since it reemerged in Toronto last fall.

“To be honest, at Cannes last year, there was this theme,” Trier said of himself and other international filmmakers working in English. “I think some of us suffered a little bit for it, because it became like people were approaching the films with this authentic cultural spectrum analysis rather than looking at what we were trying to talk about.

“We had a mixed response, but we got a lot of love too. It got a better reception in the autumn. I think there was a turning point in Toronto. It was the Cannes competition pressure.”

Among the film’s producers — Trier has said there were 21 financing bodies involved — were Albert Berger and Ron Yerxa, the American duo behind films such as “Little Miss Sunshine” and “Nebraska.”

“We’ve gone through this many times,” Berger said of the changing reaction to the film. “And we’re always nervous about Cannes. Of course, it’s the world’s premier film festival, but also there is so much noise and a desire for instant reactions and glamour and loudness. The same exact thing happened with ‘Nebraska,’ a very quiet movie. It took till the fall for people to see it on its own terms.”

Trier’s interest in formal experimentation does not mean he is not also invested in the emotions and performances in his films. It is his interest in drama that drew actors such as Huppert, Byrne and Eisenberg, who worked around his shooting schedule for “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice” to be in Trier’s movie.

“That’s what makes him a really interesting director,” said Byrne. “It could have been a sentimental film, it could have been an angry film, it could have been an unsettling film about the ghost of a woman haunting a family. But it’s shot through with the reality, an understanding of the various stages and complexities of grief. Life goes on in the most mundane ways. He captures how grief fractures within a family, the anger, the withdrawal, the deceit, the loneliness, the inevitability.”

Trier plans to make his next film in Norway later this year. After that, he may be back for another picture made in America. Regardless, he plans to keep pushing himself, to continue discovering new stories to tell and new ways to tell them.

“I want to make free movies. It makes me sound like a hippie, but I mean free in the jazz sense, playing around,” Trier said. “I come from hip-hop and punk. When I was 9, I discovered hip-hop, and why should sounds from the South Bronx speak so strongly to some kid in Norway? It was a new sound, a new way of doing things. So for me to shake things up and play around with film language, why not?”

Follow on Twitter: @IndieFocus

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.