Jane Goodall reflects on a lifelong mission to save the planet, and she’s far from finished

“So,” Brett Morgen began, “you’ve been telling your story for so many years. Do you get tired of answering the same questions?”

Jane Goodall stared back at the filmmaker, her expression unmoving.

“Depends on who’s asking the questions,” she replied.

There was no “wink-wink, nudge-nudge, ha-ha!” to her inflection, Morgen recalls now. “It was just cold.”

After all, the primatologist had not wished to be interviewed for Morgen’s documentary, period. Sure, it was a film about her life — called “Jane,” even — culled from 140 hours of footage that had been hidden for more than 50 years in National Geographic’s archives. But she’d already done so many interviews over the course of her 83 years. Couldn’t the filmmaker just repurpose one of those?

As politely as he could, Morgen relayed that there was no way that was going to happen. So, at the urging of her colleagues at the Jane Goodall Institute — “we need the exposure,” they said — she agreed to participate. She was told she would have to sit for only one filming session, which would last no more than three hours.

She ended up spending two full days with Morgen at her home in Tanzania.

“I guess Brett’s quite persuasive,” Goodall said with a shrug.

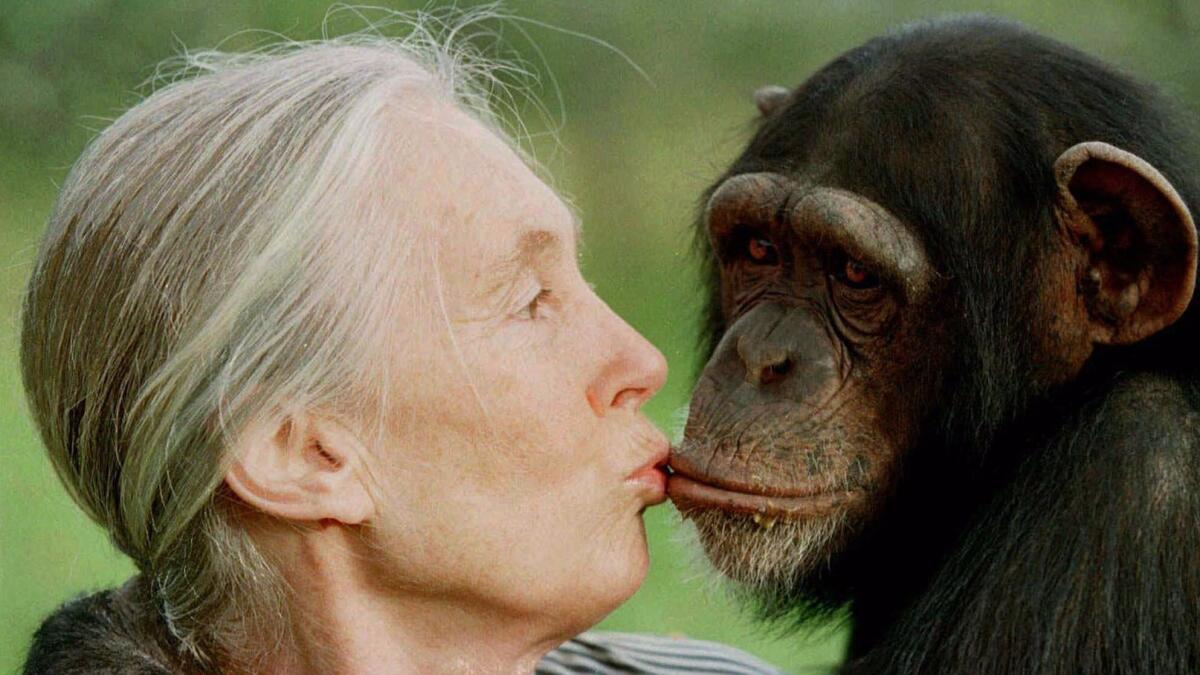

It was a Sunday afternoon, and Goodall had just come from the Toronto International Film Festival premiere of “Jane,” which opens in theaters this weekend. Her hair was swept back into the same low-slung ponytail she wore during her days in Gombe, the secluded area of Africa where she began studying chimpanzees in 1960 at age 26.

Nearly six decades on, of course, that ponytail had grayed. The everyday uniform of a twentysomething — casual khakis and Converse sneakers — was long gone. Instead, she’d wrapped a demure scarf around her shoulders.

Lest you imagine Goodall as a sweet, grandmotherly tree hugger, think again. While she exudes a gentle sense of calm, she’s serious and does not suffer fools. As Morgen observed on that first day in her home, she does not seem to relish being interviewed. She gives brief answers to questions and is reluctant to veer into any topic too emotional.

At first, this proved to be a challenge for Morgen. A major focus of “Jane” — which will be shown next year on National Geographic’s cable channel — is Goodall’s relationship with nature photographer Hugo van Lawick. Two years after she arrived in Gombe, Van Lawick was sent by the magazine to photograph Goodall’s work with the chimps; it’s his footage that Morgen pulled from to make the new movie.

But as Goodall reveals in the documentary, she quickly realized she was just as much of a subject of interest to Van Lawick as the chimps were, and the two fell in love. They were married in 1964 and had a child together, whom they nicknamed Grub.

While Goodall has discussed this period in her life extensively, she has always focused on her primate research. She’d never discussed her romantic relationship in detail, and Morgen found that many specifics of the courtship had escaped her.

“I had to pull it out of her. It was difficult for her to access,” said the filmmaker, best known for directing the Kurt Cobain documentary “Montage of Heck” and “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” about Robert Evans. “After Day 1, I was like, ‘I’m not getting what I need about Hugo.’ So I showed her the footage where she and Hugo fall in love, and the memories started coming back.”

The couple would eventually divorce in 1974; Goodall wanted to stay in Gombe and focus on her work, while Van Lawick’s focus had shifted to photographing wildlife in the Serengeti. Indeed, Gombe still holds a special place in her heart — that day in Canada, she wore a necklace in the shape of Africa with a piece of tanzanite embedded in it to identify Tanzania’s location. She still goes there twice a year for a few days, and she always insists on spending one day alone in the forest.

“That’s how I refresh my spirit,” she said. “But it’s a very different Gombe. There’s so much tourist accommodation, so if chimps are nearby somewhere I can get to easily, there’s always tourists. And that doesn’t interest me.”

Since 1986, Goodall has shifted her emphasis from research to conservation, traveling the world giving lectures, visiting schools and teaching young people about the environment. She spends more than 300 days a year on the road, and has not spent more than three weeks at home, consecutively, in more than three decades.

She hates all of the travel — “horrible,” she said, shaking her head — and tries to be as eco-friendly as she can while crisscrossing the globe. Roots & Shoots, her youth service program, plants millions of trees each year to partially offset her carbon footprint, and she’s come up with different strategies to conserve while staying in hotels.

“Most of the bins are lined with plastic, and so somebody will stay one night, drop a tissue into three different bins, and all three of those plastic bags will be tossed,” she said. “I always save something that I have and put all the trash in that so I don’t touch the bins. I get livid if some of my friends come in and dump something in a bin.”

Asked why she keeps up such a rigorous pace, Goodall is quick to respond. “I have a message to give,” she said plainly, “and I don’t know how many years I have left. I care about the future and the wild places and my grandchildren.”

It’s a sentiment that brings Morgen to tears — and he’s not a weepy guy. After making so many films about hard-partying rock ’n’ rollers like Cobain and Mick Jagger, he was at first reticent to focus his attention on Goodall. He didn’t know anything about her and thought she’d be really earnest, “like St. Jane.”

But after spending time watching the old footage — and getting to know her on the film’s promotional tour — Morgen holds deep affection for Goodall. Any time they’re asked to take a photo together, she makes goofy faces at him — “she likes to have fun, but people are so reverential around her,” he said.

“She’s doing what she wants to be doing. I’m not going to say she’s the most selfless person in the world,” the filmmaker said in L.A., the morning after another screening of the film — this one at the Hollywood Bowl, where a live orchestra played the score that composer Philip Glass wrote for “Jane.” “Here she is at the twilight of her life, trying to save the world for my children. She knows her days are numbered.”

He started to cry, and paused for a minute or so.

“Last night when I said goodbye to her,” he said, choking up again. “Sorry.”

“Do you want water or something?” a publicist asked.

He shook his head and after composing himself, talked about how he’d walked up to Goodall’s car after the screening. She’d had a wonderful evening, and was one of the last to leave the venue. She rolled down her window and asked Morgen: “We did good, didn’t we?”

“We did really good,” he answered.

“I told her, ‘I hope this film can take some of the load off your back and you understand that when you can’t be somewhere and when you’re not with us, this film will carry on your messaging,’” he said. “I’m not an earnest person, but her selfless dedication — it’s humbling. It’s impossible to watch Jane and not ask yourself, ‘If she can do that, what can I do?’”

Follow me on Twitter @AmyKinLA

ALSO

Jane Goodall responds to being quoted in Ivanka Trump’s book ‘Women Who Work’

Harvey Weinstein is done. But what about Lisa Bloom?

The fallout: How the Harvey Weinstein scandal exposed sexual harassment as Hollywood’s dirty secret

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.