Q&A: What a new Sundance documentary reveals about Harvey Weinstein

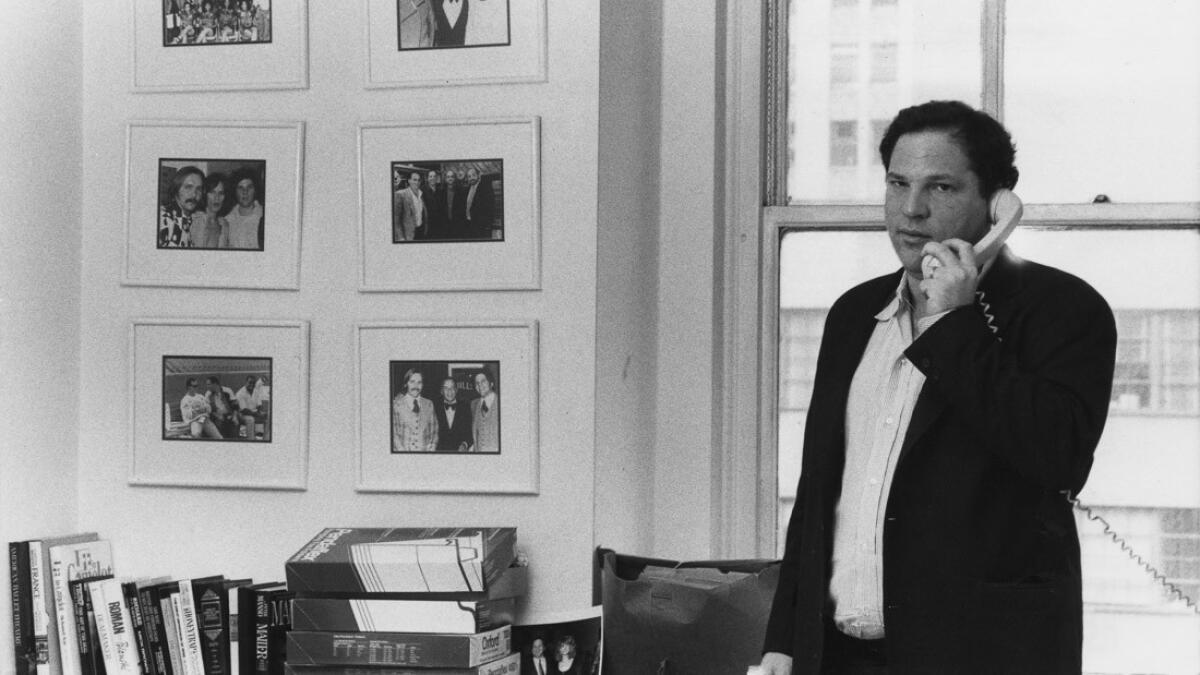

The Sundance Film Festival was where Harvey Weinstein made the moves that helped to cement his status as a Hollywood power player, acquiring so many of the independent films he hoped to turn into Oscar winners.

But the disgraced mogul will make a far less glorious return to Park City, Utah, this year when a new documentary about him premieres at the festival on Friday evening. The film, called “Untouchable,” explores both Weinstein’s rise to showbiz success and his fall from it, interviewing some of the hundreds of women who have accused him of sexual misconduct over the past year.

Directed by British television veteran Ursula Macfarlane, the film doesn’t aim to reveal new allegations about Weinstein’s behavior. Instead, the documentary attempts to explore why the film executive engaged in that behavior, beginning with those who knew him when he was a college student promoting concerts in Buffalo, N.Y. Through interviews with accusers including Rosanna Arquette, Caitlin Dulany and Paz de la Huerta, a visceral portrait of the pain Weinstein caused over the decades takes shape. (Weinstein has repeatedly denied all charges of nonconsensual sex and sexual misconduct.)

The night before she flew from the U.K. to Utah, Macfarlane spoke with The Times about why she chose to make a documentary about Weinstein, her desire to interview the man himself and how she thinks her film can contribute to the #MeToo movement.

When did you begin thinking about making a documentary on Harvey Weinstein?

Producer Simon Chinn asked me to do it a month or so after the first story about Harvey broke, but we didn’t actually start filming until May 2018. I didn’t hesitate in saying yes because I felt this is such a moment for our culture and we needed to capture this moment.

I think as a woman, those stories really spoke to me. I found them heartbreaking. It felt quite personal, the stories you were hearing. What was interesting for us was to try to understand the context in which this all happened — the power dynamics, the power he garnered and the image he honed that enabled him to allegedly do all this over a period of decades. Yes, the #MeToo side of it was fascinating and emotional. But I think it was also about building a portrait of a man in power. We tried to build it like a Greek tragedy. Coming in as an outsider who hadn’t crossed Harvey’s path, I was fascinated with him as a human being. How does he get like that? Clearly, he had this kind of charisma and this ability to never take no for an answer.

Were you at all conflicted about further shining a light on a man who allegedly caused trauma for so many women?

I know what you’re saying. I think he is a larger-than-life figure. I felt we did need to try and understand him and try to understand what allowed him to leverage his power and his influence to get the things he wanted. If it’s true that he abused all these women, that is a lot of women that he managed to exploit. The insiders that we spoke to painted a quite fascinating portrait of this guy who was as compelling as he was abusive to them.

Did you try to interview Weinstein himself?

He’s a fascinating man, and we made a lot of requests to meet him and speak with him. I would have loved to, but I realized it was obviously going to be very unlikely. They were very short one-liners from [Weinstein’s former attorney] Ben Brafman saying he wouldn’t participate. I never expected them to come back and say, “Yeah, sure!” But you always live in hope. Oftentimes, people come through at the last moment. But obviously, his lawyers will tell him not to talk to anybody. As I was making this, I had an imaginary dialogue with Harvey in my head.

How did that go?

He didn’t say very much. In my wildest dreams, he would sit and I would ask him questions. And then he would say no comment, like he’d had a reality check. But having a camera on someone’s face — that in itself would be interesting. At some point, maybe Harvey will talk, and I would love to be the person he spoke to.

Given there were hundreds of Weinstein accusers, how did you decide who you wanted to interview?

We had to be quite careful, because obviously we didn’t want to let anybody down. So we went the routes that other journalists have gone and approached people who had already spoken. But we were quite keen to tell the stories of some women who hadn’t spoken, at least not on camera. Our approach was that we wanted the alleged abuse to reveal something different about Harvey and something about his M.O. And also a different time scale. Once we knew we had somebody to whom this happened four decades ago, we wanted to get up to a span of quite recently. And actually, a lot of his M.O. is very similar — and that’s rather chilling.

Were there Weinstein accusers you wanted to include who turned you down, like Ashley Judd or Mira Sorvino?

There’s a lot of women who didn’t want to take part who felt they had already spoken, and obviously we respected that. We contacted everybody — all the people that you know about. We didn’t have lots and lots of women in the film, and that was quite deliberate. We wanted to give them enough time and space, not just a long list of women who could speak for a minute or so. Rosanna Arquette is quite high-profile, so we were glad to have her. [Arquette is also expected to attend the premiere.]

What do you think a film can bring to the Weinstein story that perhaps print articles cannot?

Jodi [Kantor] and Megan [Twohey] and Ronan Farrow produced articles that listed the allegations and did a lot of work on complicity. We couldn’t possibly do that in a 90-odd minute film. I think the thing about a film is we were able to tell it in a more dramatic way than perhaps a newspaper article can do. Even though it’s not fiction, it’s fact, we tried to structure it as a gripping tale. I think it’s visceral in a more immediate way when you actually sit there listening to these women’s stories. It’s kind of a cumulative effect.

How do you feel about the film premiering at Sundance, where some of Weinstein’s alleged misconduct took place?

It feels like the perfect place in some ways, but that sounds a bit glib. I think it’s very bittersweet. Harvey had an influence on Sundance and changed the game there. It became a different kind of festival because of him. And people like Rose McGowan have accused him of abusing them at Sundance. But I think it’s a powerful place to premiere, because it feels quite symbolic. There’s a lot of people there who will know Harvey. I don’t think it’s going to be an easy viewing.

What kind of legal vetting did the film have to go through?

Obviously, you have to vet the credibility of all the incidents in question and offer Harvey and Bob [Weinstein, Harvey’s brother and former business partner] a right to reply. And as I said, we contacted Harvey several times throughout the process. We had to corroborate every allegation as far as we could, and obviously there were some things we had to take out, but we pushed it as far as we could to let those women have their voice and say what they wanted to say. For their own sake, you have to make sure it’s sound.

Do you get the sense that the public is tired of talking about the #MeToo movement?

I hope not. I always try to be optimistic, and I think film is the most powerful medium. There has been a backlash over the past year. Whenever there’s any kind of feminist movement or uprising, there’s always a backlash. I feel the timing of our film is good, because a lot of these women’s stories are being pushed aside, and Harvey’s case has really had the headlines over the last year since his arrest.

How do you feel your film can contribute to the movement?

When you watch something so visceral and it makes you feel something very deeply, I think that’s a very powerful way to get a conversation going. But it needs so much more than that. We need to change structures and change employment law and legislation. All those things take a long time. At Sundance, there are a lot more women filmmakers this year. I’d like to think that if you can get rid of people like [ex-CBS chief and accused abuser] Les Moonves and Harvey Weinstein, these people can be toppled. I’d like to think people aren’t going to dare behave like that, but human nature isn’t that simple.

I’ve got two sons, and I want them to grow up respecting women. I want them to know that if they’re in a work situation, they can call it out and say it’s not OK. In that sense, I hope the film is a positive thing. But there’s a lot of structural change that needs to happen.

FULL COVERAGE: 2019 Sundance Film Festival »

Sundance 2019 Film Festival: See the latest video interviews

Video: Behind the scenes of the L.A. Times 2019 Sundance photo/video studio

Video: The 2019 Sundance Film Festival Boomerang Supercut

Video: How do you make the most of a small budget?

Video: Cast and filmmaker discuss trusting each other while shooting 'Premature'

3:12

Video: 'Brittany Runs a Marathon' breaks conventions and stereotypes

Video: Jillian Bell is tired of getting scripts about body image issues

Video: Jillian Bell lost 40 pounds for her role in 'Brittany Runs a Marathon'

Video: 'Brittany Runs a Marathon' actors break out of their sidekick roles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.